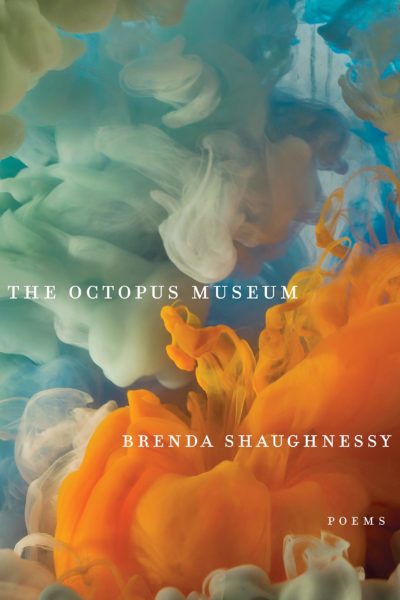

The Octopus Museum

by Brenda Shaughnessy

reviewed by Calista McRae

The title of The Octopus Museum, Brenda Shaughnessy’s moving fifth book, is explained partly by the table of contents, fashioned as a “Visitor’s Guide.” It presents “five exhibition spaces” put together to chronicle a diminished and curtailed species, one possibly nearing extinction. Each poem is thus one of the relics gathered by cephalopods, the new reigning life-form, now that humans are no longer in control. At moments, the way that The Octopus Museum fuses lyric poetry with approaching dystopia is reminiscent of the bleak, tech-heavy environment in Cathy Park Hong’s Engine Empire (2012), though Hong pictures a world of monitoring and VR and depression, and Shaughnessy’s is one where “since we used all the air conditioning it’s become impossible to think things through.”

Almost every poem here is situated in a fluctuating present tense. Sometimes the speaker is in a distant future; at others, she seems to be in or near the current actual age, “the era of hell-wealth” and of children’s birthday parties, where “points [are] oscillating to drill collective holes in the Big Shroud everyone’s making for everyone else equally.”

The poems are permeated by the terms of climate change, as heard in nervous trains of thought like “My own mind is not leading. I’m unleaded. I’m gasoline.” Its aphorisms can be self-condemningly witty—“Tell myself the weather ruined my plans, though it’s me ruined the weather’s”—or explicitly bitter: “There’s no privacy outside. We’ve invaded it.” Taken as a whole, The Octopus Museum gets at how thoughts circle obsessively, with varying ratios of fear, guilt, anger, bewilderment, and distraction. Some of its speakers remember their species’ liking for plastic, others address their former lovers, and another (in a clipped, three-line poem) recalls a dessert they never had the chance to try.

At the same time, the book does not just present the uneasy motions of an inner life, but looks outward, to American systems. Like a Martian poem, the device of the museum allows Shaughnessy to examine the senselessness of consumerism (which she ventriloquizes: “I love this local company, especially because for every order—and this is so cool—they make a tax-deductible contribution to honor and support the world-famous Pacific Garbage Patch, in your name”), health insurance laws, gun violence, racism, and sexism. One scathing example is “Are Women People,” a six-part document composed by “cephalopod researchers” attempting to understand why women “between the ages of thirteen and fifty” are not people, or why people of color need to be especially scrupulous in renewing their forms of identification. The word “people,” occurring about a hundred and fifty times, loses all meaning.

While “Are Women People” includes pages of questions, multilevel lists, and hefty blocks of text, almost all of the other poems are in prose stanzas, not quite paragraphs; the unit is usually about three sentences long. It suggests austerity, appropriate to a future drained of variation and of most pleasure, and it creates blocks of thought that do not necessarily evoke a sense of tradition or coherence or resolution; such qualities would not fit what these poems are thinking through. The book’s language, similarly, is often dominated by seemingly immediate, ordinary speech. “Nest,” for example, sounds like a written-just-then record of stress and remorse (“and all the info I said // above, which is all the info I have at this point”), brought to a head by an encounter with a wasp, “not a good bug like a bee // or a spider.”

At the same time, however, the linguistic play of Shaughnessy’s earlier books is still present: in a more figurative poem, insect-like creatures are “living question marks, leech-pieces, worm eyes, segments of fertile sediment,” and “little glowing spitballs.” And Shaughnessy’s warm, seemingly candid, intensely frustrated voice—“I cling to this life. I’ve taped myself to it like a card on a gift”—is audible throughout The Octopus Museum, though her sense of humor is now sometimes closer to a sense of irony. The book is elegiac, funny, affecting, and frightened, able to lament one’s current state and to imagine one’s final state, in a single line: “Bugs don’t have to be what they’re not, in their spirals and blind shapes overturning, eating you.”

Published on September 3, 2019