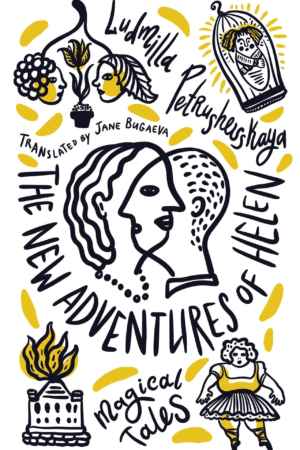

The New Adventures of Helen

by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, translated by Jane Bugaeva

reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

“Once upon a time” is perhaps the original narrative “hook” that, through its dissemination throughout oral and written storytelling traditions, has the power to transport anyone of any age into another time and space. The seven short stories in Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s new collection, The New Adventures of Helen, all open with the trusty phrase, the familiarity of which only enhances her stories’ subversion of the reader’s expected end point: a land of “happily ever after.” Her protagonists’ sufferings may be transformed by magic-makers, singing animals, and sparkling partywear like in the fairy tales of yore, but these are “new adventures”—modern fairy tales where magic dwells alongside harsh reality, and our heroines live “complacently ever after” with their unpredictable turns of fate. Rather than a doorway to a fantasy, “once upon a time” becomes an invitation to open our eyes to our unfiltered reality, comprising magic and misery. It may be too much to handle—or it may offer sympathy, comfort, and a way to cope with the stranger-than-fiction world we live in.

Renowned as a playwright in her home country of Russia, Petrushevskaya is the author of over fifteen books, including two best-selling story collections translated into English in 2009 and in 2013. Her style is a melange of acerbic wit, profound psychological insight, and brevity that’s perfect for our age of shrinking attention spans and proliferating tragedy. There’s an undeniable, perhaps genetic, influence of the great Russian masters—Chekov, Tolstoy, Leskov, Nabokov—in her words, but they are also infused with an attention to modern concerns that impresses, given Petrushevskaya’s age; at eighty-four years old, she could easily steep her writing in nearly a century’s worth of cultural ups and downs, and yet, as she does in this collection, she looks themes like excess and materialism straight in the eye.

The New Adventures of Helen begins its journey through the rough seas of reality with its titular story, which updates an ancient fairy tale, perhaps the first in all of literature: the story of Helen of Troy, whose desirability launched both the Iliad and the Odyssey. It’s said off the bat that “we all know” Helen is reborn every thousand years, an assertion that underscores the universality and relevance of fairy tales even if this particular detail didn’t come from Homer’s lips. The Helen du jour is born from the sea and is (of course) shockingly beautiful, yet in our age of distraction she goes completely unnoticed. She unintentionally falls into the role of prostitute—an interesting reimagination of Homer’s Helen—complete with a “look” that, in Petrushevskaya’s alienating narration, reveals how strange our conventions of beauty are. Doing her makeup, Helen draws “two commas over her eyebrows, fishtails on her eyes, and a red heart around her lips, and then she roughed the apples of her cheeks.” Rather than being whisked away and having a war fought over her, our Helen has a pleasurable but short-lived affair with a billionaire. Petrushevskaya tells us that their happily-ever-after “maybe” happened, “but not anytime soon.”

The disappointments of women on both ends of the youth-and-beauty spectrum fill these stories. We hear of one woman, Nina, whose otherwise good looks are eclipsed by her huge nose—a feature she eradicates with magic, thus removing her most memorable quality and almost missing out on love (before it grows back). A pair of elderly sisters, Lisa and Rita, stumble upon an ointment that turns them into children, but rather than enjoying their newfound youth, they find themselves frustrated that they are not respected, considered uneducated, and left dependent on a kindly, if anachronistic, mother-figure. Even when men appear to be the protagonists, as in “The Prince with Gold Hair,” it’s the determination of women that saves the day. When this prince and his mother, the queen, are mistakenly imprisoned due to the king’s oversight, it’s her forgiveness that brings about peace for the entire land. Fleeing the kingdom, the mother and son sail the world and eventually settle down in another, more modest “kingdom” of their own—having “sold their yacht and bought an apartment in the suburbs.”

The understated magical realism of these tales makes it all too easy to slip into worlds where body parts regenerate like newt tails, or—as in “Nettle and Raspberry”—the death of a special flower engenders the parallel, tortured demise of its owner. Petrushevskaya’s casual employment of these devices isn’t a parody, but rather a reflection of how the modern conveniences we take for granted—plastic surgery, Instagram filters, online dating apps—promise a truly absurd, fantastical life that somehow we’re surprised to not be more satisfied with. If these women, under the influence of actual magic, can’t make all things fairies and singing animals, what promise do algorithms and biohacks bear?

Present throughout this questioning of perceived beauty, success, and value, however, is a tone of much-needed levity that offers perhaps the best—and most realistic—ending to our own living fairy tales: happily enough ever after. None of these women convey the sense of hopelessness and fatalism that you might expect after reading of their trials. They accept what’s in front of them and, more importantly, continue to believe that future magic is possible. To realize that the variety of “once upon a time” includes our time might inspire us to rewrite the stories of our lives as we live them, rather than waiting for time to rebirth and distort our stories into antiquated, mythic illusions. We are reassured that all the flaws, disasters, and triumphs have a rightful place in the narrative, no matter when it’s being read.

Published on May 17, 2022