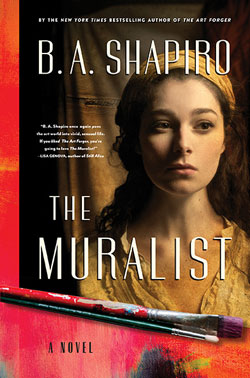

The Muralist

by B. A. Shapiro

reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

What do you get when you mix artists and politicians? It’s a recipe for conflict proven by multiple instances in American history, one example being during the tenure of the Depression-era relief organization called the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Designed to provide work for artists, among other unemployed individuals, through the commissioning of public art like murals, the WPA had all the best intentions of bringing Americans a dose of sorely-needed culture, beauty, and financial security when nearly everything else was grey and dismal. Naturally, though, the gods of art made it such that during this time of artistic encouragement and goodwill, an aesthetic revolution was brewing among those called upon to create safe, pro-USA works of art for public consumption. That movement, one of the richest in twentieth-century art, was Abstract Expressionism. And in B. A. Shapiro’s new book, The Muralist, the tensions of this time period and its iconoclastic characters are brought to life.

Shapiro is a Boston-based novelist whose most recent book, The Art Forger (2012), took on similar themes in a fictionalized exploration of the 1990 theft from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, a mystery still unsolved. There, she conjured a secret tryst between Edgar Degas and the novel’s protagonist, and in The Muralist one finds similar entanglements between real artists and fictional characters. The novel switches between past and present as we meet Danielle Abrams, an art auctioneer at Christie’s who discovers a hidden piece of a mural painted by an unnamed artist she believes to be her grandmother, Alizée Benoit. Alizée’s story takes place in New York in 1939-1940, where she works for the WPA with her friend Lee Krasner (the wife of Jackson Pollock). Together, they become aware of the artistic protests fomented by works like Picasso’s Guernica, and thanks to a serendipitous encounter with Eleanor Roosevelt, Alizée is inspired to create a polemical work of her own: a three-by-six-foot mural called Turned, a critique of the United States’s rejection of European refugees during the war. Eleanor manages to get FDR to support the work, so all seems to be going well—until Alizée is committed to an asylum against her will, sending her lover (Mark Rothko) into an emotional tailspin. Her friends divide the mural into small squares hidden behind their own canvases—the squares that Danielle discovers by accident—but the mural and the artist are never reunited, as Alizée “disappears,” living under a false name for the rest of her life to escape political accusation for her work.

The Muralist has every ingredient of seductive historical fiction: lead characters whose fiery reputations make for dramatic moments and relationships, and a backdrop so intense in the American imagination that this addition to the canon of Depression novels is refreshing. Alizée is a strong character in her own right—her backstory is believably traumatic (her parents, both scientists, are killed in a lab fire at Harvard), and her name seems seemingly elided from artistic and historical record. Her Turned could be discovered (or painted) today, so relevant it is to contemporary artistic and international political debates.

What takes away from Alizée’s story, though, are the caricatures built around her historical counterparts. The Roosevelts in particular come off as mere ciphers in the book, whereas their influence over art during the time, particularly Eleanor’s, deserves more serious attention. As people who talked about private and public affairs in the same breath, they fall maddeningly flat. The artists—Krasner, Rothko, and Pollock—add more melodrama than drama, talking about art and the implications of their work from a retrospective vantage point, that of an artist looking back and categorizing and analyzing rather than living and creating from their tumultuous inner energies.

As a result of the competition between past and present, Danielle’s uncovering her grandmother’s secret identity underwhelms in providing a compelling narrative pull. Her presence is a stand-in for Shapiro’s own authorial curation of this historical moment, especially as the juxtaposition of characters’ voices in alternating chapters makes it impossible for a reader not to glean, from the start, that Alizée is the mystery artist behind the hidden canvases. Had she been able to maintain a more singular footing in the novel’s structure, Alizée would have carried her own story with brio and intrigue, and led readers to wonder what might have happened differently had such a work as Turned been executed for the benefit of the past, present, and future.

Published on February 9, 2016