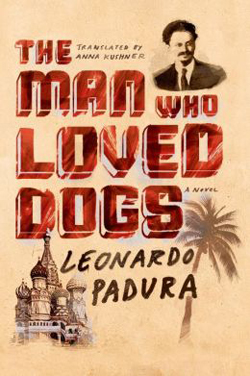

The Man Who Loved Dogs

by Leonardo Padura, translated by Anna Kushner

reviewed by Gabriel García Ochoa

Who is the man who loved dogs? This is perhaps the most beautiful mystery in Leonardo Padura’s newly translated novel, The Man Who Loved Dogs. Is it Leon Trotsky, dotting on his borzoi, Maya, as he struggles through the life of an exile? Or Iván Cárdenas Maturell, a Cuban writer turned impromptu veterinarian? Perhaps it is Ramón Mercader, aka Jaime López, the NKVD-trained assassin entrusted with Trotsky’s murder, who wanders the beaches of Santa María del Mar as a ghost of his former self, observing Ix and Dax, his Russian wolfhounds running down the shoreline?

Padura is one of Cuba’s foremost writers. He is a journalist and screenwriter, and has published almost a dozen novels, as well as short story collections and essays. The best-known English translation of his work is a set of four detective novels that take place in Cuba, The Four Seasons. In 2012 he was awarded Cuba’s National Literature Prize, the country’s highest literary accolade.

The Man Who Loved Dogs begins in Havana in 2004, as Iván Cárdenas, a washed-out literary talent, starts telling the story of how he met the mysterious Jaime López in 1977. The story then jumps to the start of Trotsky’s exile in Alma-Ata in 1929, and continues in 1930s Barcelona, where Ramón Mercader del Río is recruited by Soviet forces to begin the long indoctrination and training that will culminate in Trotsky’s assassination. Through the braiding of these storylines Padura discusses different aspects of Cuban life: corruption, homophobia, truth, creative freedom, and Stalin’s debasement of the Socialist dream.

A trademark of Padura’s fiction has always been his open criticism of Cuban society, and one of his greatest gifts as a writer is his ability to skirt the abyss of censorship without tumbling in. Politically speaking, The Man Who Loved Dogs is one of his most daring works. The book brings together elements of Padura’s previous novels: like Adiós Hemingway, the first of his books to be translated into English, and La novela de mi vida, The Man Who Loved Dogs is a historical novel. It took Padura almost six years to write, but despite the wealth of detail and the historical density of the work, Padura insists that the work is pure fiction. “Remember that we’re talking about a novel, despite the overwhelming presence of history on each of its pages . . . in this novelistic tale—I repeat, novelistic . . . ” This is Padura’s well-honed diplomacy at play, pushing institutional limits and at the same time paving an escape route of ambiguity for his text.

According to Padura, the idea to write The Man Who Loved Dogs first came to him in 1989 after a visit to the museum that was once Trotsky’s home in Mexico City. If you have been there, it’s easy to notice the lack of light inside the house. Most of the windows are bricked up, and the heavy doors—three-inch-thick, bulletproof steel—swing slowly on their hinges. It is a house of fear. Although Mexico City’s suburban sprawl engulfed the placid town of Coyoacán long ago, when you walk next to Trotsky’s cacti garden in the shadow of the unusually tall walls, or stand in front of the rabbit cages he used to tend, it is easy to imagine what it would have been like to live there seventy years ago: the isolation, the seclusion of fear.

Padura’s novel encapsulates this feeling. In The Man Who Loved Dogs, Stalin’s presence is always felt, stretching beyond Europe and across the Atlantic. As Trotsky’s influence begins to wane during his exile, the novel charts Stalin’s corresponding rise to power and his consolidation as a tyrant. But Stalin is the only unredeemable villain in the story, and part of the novel’s interest lies in its ability to generate in the reader, if not always compassion, at least a strong sense of empathy for its main characters. We admire Trotsky but we know he is not perfect; the excesses committed during and after the revolution weigh heavily on his soul, yet as the current underdog, he is a sympathetic figure. Likewise, Ramón Mercader’s logic of murder is magnetic, and Ivan’s mediocrity understandable.

Published on June 24, 2014