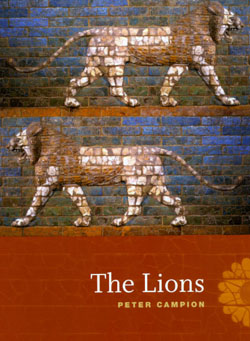

The Lions

by Peter Campion

reviewed by William Doreski

The poems in Peter Campion’s second book explore the convergence and divergence of individual lives, and their intersection with larger social and historical forces. “We suffer in the ways our lives have led us,” he notes in “Lethe.” Convergence produces sex and shared observations, but the divergence into private experience produces more dramatic emotional moments:

So tenuous

the links. My skin was wholly taken over

by my pulse, and my pulse was streaming so fastI wondered, if it were cut, what scrubbing would it

take to clean the blood from the floor boards.

As these lines illustrate, under sufficient pressure Campion’s poems sometimes tend toward cliché. But their calmer surfaces are often elegant and graceful, and “Protest” opens with a remarkable image:

They showed us on the evening news. Our breath

was visible. So our chants appeared as impish

volleys of vapor as the camera panned.

The intersection with larger forces is more problematic. The monumentally serious subject matter (“life” with an elided capital L) of Campion’s poetry is appealing but risky. The compact and graceful poem “Bad Reception” begins with a TV image of ongoing warfare: “Out of the breech of an M-16, shell-casing cut / a golden arc across the picture.” The TV falters but the image lingers, enflaming the speaker’s imagination: “It feels like charging up, getting high: / the images whack through deserts and towns / while the men take fire . . . ” But then the poem turns resolutely domestic, as if in the end the drama, shock, horror, passion, and evil energy of life devolve into the most banal experience: “My entire life in this household with her. / How infinitesimal we are, hidden here / inside the sweep of what we will not stop.”

In poem after poem, Campion insists on the smallness and insignificance of the individual or the family in the face of great forces of history and change. Yet if we overlook the frequently sententious closures, the bodies of the poems dramatize a position that belies this humble stance. This position is that of a sensitive observer who bears witness to forces he cannot redirect but can inscribe with great effect on the consciousness of readers. Even his third-person poems demonstrate the power of witness and experience to atone for human nature. “Lethe,” one of his best poems, traces the unsatisfactory relationship between vision and action:

Three times he tried to throw his arms around

his father’s neck. Three times his father slipped

his grasp: weightless as air or shapes in dreams.

Reprising the famous scene in the Aeneid, the poem allows the elusive father in death to explain the Great Chain of Being and explain why the world of Campion’s poems seems so gloomy. Human nature is at fault, and persists even after death:

They can’t discern the prisons they live in.

Even when life sputters away from them

so many cripplings engrained in themremain.

Not all of Campion’s poems explicate their own arguments. “Recurring Dream in a New House,” for instance, presents a series of vivid images and even closes with an appealing if slightly grim picture: “the dark // slinks off behind the buildings and the sun / drips from the cars and trash and streaming bark.” Campion’s strongest and most pervasive imagery is water-based—mist, rain, “wine-colored water,” a fountain, a hotel swimming pool. Spill, drip, and seep are favorite verbs. When Campion keeps his eye on the world he can be a compelling poet of natural process, surfaces, textures, and atmosphere. But when his poems insist on our human insignificance they seem to betray their own intelligence. And even when their closures are not especially negative they are sometimes too bald, as with “Sparrow,” which ends: “the same way / we survive / our happiness / and also: sorrow.” Aside from the awkwardness with which Campion handles the very short line, this passage illustrates the unhappy concern with meaning that haunts Campion. He seems to fear that the argument of his imagery might not be clear enough to his readers. But why tell what he can show perfectly well? When Campion trusts his imagery he makes his point clearly enough without unnecessary explication. But then should a poet care about making points? Maybe it’s better to spill, drip, and seep across the page without worrying where the poem flows.

Published on March 6, 2015