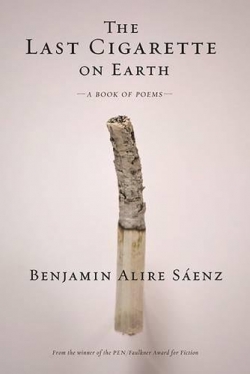

The Last Cigarette On Earth

by Benjamin Alire Sáenz

reviewed by Zack Anderson

“I feel your pain,” writes PEN/Faulkner Award-winning fronterizo poet Benjamin Alire Sáenz in his seventh collection of poems. “Imagine holding on to that phrase. Not / Just on your tongue but in the softest part of your flesh, / The part that’s most likely to bruise, the part that’s tender / To the touch.” Layering explorations of trauma, mourning, intimacy, queerness, and love, The Last Cigarette On Earth dramatizes the tension between violence and desire, the tongue and the bruise.

Sáenz’s lines are at their best when they expose intimacies in unexpected places. Most often, this occurs at the intersection of violence and eroticism, mediated through the double-edged blade of the human body. “A hand is a thing that can touch, a part of the body / That can torture, that can kill,” he reminds us early in the book. In the poem “Touch,” the speaker daydreams about being tortured by a cartel and narrates the encounter in the third person:

A man grabs him by the chin

and lifts his face up towards him and says: ‘We are

going to cut off your balls.’

[…]

The men in the room are serious and sincere. They

have no irony in them. They believe this is necessary.

They believe he deserves this. And so he hears

himself tell them: ‘Go ahead. Go ahead and grab

my balls and cut them off. Be quick and cut them off.’

Like much of The Last Cigarette on Earth, “Touch” is primarily concerned with relations between men. The castration threat materializes alongside the gesture of the cartel man cradling the speaker’s chin as the speaker accepts the terms of the torture, creating a surprising amalgam of intimacy and threat between the two men. “Touch” highlights Sáenz’s sense of balance that runs through the book, as the poem closes with the tender and gentle wish to “touch someone. Not / to hurt, not to torture. But to take his own trembling / hands and touch another man’s hands / in a wordless and untortured moment.”

In contrast to the brutal intimacy seen in “Touch,” the centerpiece of the collection is the eight-page love poem, “For Carlos.” Off-kilter rhymes and fragments of Modernist poems and Annie Lennox songs stage the speaker as a latter-day Prufrock, struggling against addiction and alienation toward a sense of domestic harmony: “You and me. / In different rooms. Once I loved this place and made it mine. / I was just a passing tenant. That love is spent. It’s time—” Along the stream of its volubility, “For Carlos” offers the reader small eddies of images like the sound of rain, a ray of sunlight slicing into the house, the drift of a cigarette. Sáenz effectively pits these quiet moments of emotional clarity against the chaos of “the meth, the booze, apocalyptic nights” that characterize the relationship in the poem.

Despite the book’s moments of affective lucidity, Saénz’s speaker occasionally strays into a territory that feels voyeuristic or flippant, such as when he sees a homeless person at 7-11 and remarks, “You have / Already made up a story about him and his pedestrian / Afflictions.” Although moments like this may strike a sour note, they do speak to Saénz’s aptitude for honestly engaging the contradictions of the human mind. In the poem, “With the Flu: Lying in Bed For Days,” the speaker meditates on the disappeared women of Juárez from the confines of his sickbed:

You are disappearing into the desert. You will become one with all the bodies of the women who were lost there. Together you and I and they will become a we. And we will all rise from the dead and haunt the world until the killings stop. You smile at the thought and when you wake, you are happy. You have never been this hungry. You make potato soup.

Sáenz’s pronoun usage complicates the poem’s subjectivity in interesting ways, as the second person implicates the reader in the disappearance and the production of a new, undead body politic as a result of historical violence. In this sense, the Juárez poems recall Raúl Zurita’s porousness of bodies and landscapes or Dolores Dorantes’s use of polyvocality. Here, Sáenz juxtaposes the interesting deterritorialization of the subject with the bodily pleasure of potato soup, returning always to the inescapable factory of the body. The soup becomes at once an emblem for the inescapable solipsism that accompanies owning a body and a poignant image of helplessness on the broader social scale. While at first glance, this strategy runs the risk of trivializing real trauma, this poem forces the reader to grapple with the bewildering incongruities inherent in global capitalist life.

The Last Cigarette on Earth invites the reader to occupy spaces of contradiction, falling between love and hate, tenderness and violence, pain and pleasure. It suffers under the weight of its own length, but when it delivers its flashes of unexpected intimacy, the collection shines. In the end, Sáenz argues that simple human contact can be a shield against the atrocities of the world, that “it would be so beautiful / to touch someone like the morning light is running / its fingers through his room.”

Published on November 28, 2017