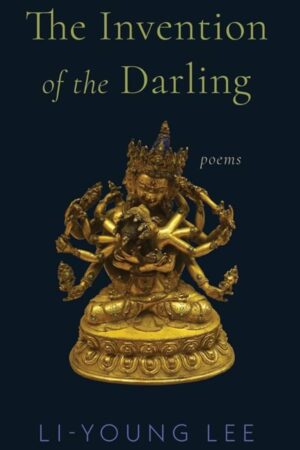

The Invention of the Darling

by Li-Young Lee

reviewed by James O'Connor

American poetry is full of dead fathers—Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy,” Theodore Roethke’s “My Papa’s Waltz,” and Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays,” to name but a few. However, of poets writing today, nobody has written about their father more extensively than Li-Young Lee. In 1990, Lee won the Lamont Poetry Prize for The City in Which I Love You , which contains several elegies for his father, among them are “Arise, Go Down,” and “My Father, in Heaven, Is Reading Aloud.” In “Arise, Go Down,” Lee writes, “I grow more fatherless each day.” It’s a simple, mournful line of great power that turns out to be more than a little prescient.

Now, thirty-four years later, in The Invention of the Darling, the father is still a haunting, benevolent, and an almost divine presence, inspiring Lee to some of his finest poetry:

And I wake now a man,

my sleep sometimes still infringed upon,

not by dreams of loved ones disappearing,

but dead ones come back strongly

loved and loving.

In “The City in Which I Love You,” he writes, “Like the sea, I am recommended by my orphaning.” Lee is still recommended by his orphaning, and now there are elegies for his mother as well. Even the love poem that ends the book about the darling ends with thoughts of her. It might seem an odd way to end a love poem, but Lee knows that “True love looks out / through death’s unswerving gaze,” and if a love poem ends with thoughts of his dead mother, so be it.

Yet despite “death’s unswerving gaze,” The Invention of the Darling seems to insist on transcendence. Wings are ubiquitous. In some poems, the word “wings” appears as many as seven times. One searches for the poet who once wrote “I’ll measure time by losses and destructions.” Now the poet seems more likely to measure time by invoking wings and “singing, Holy! Holy! Holy!”

In “The Cleaving,” the last poem from The City In Which I Love You, Lee writes of becoming an American, eating “these Chinatown / deaths, these American deaths … And I would eat Emerson, his transparent soul, his / soporific transcendence.” To call Emerson’s transcendence “soporific” is a bold presumption by a young poet, and one might frown at the temerity of it, but The Invention of the Darling can also be accused of the same sleep-inducing transcendental proclamations:

What we can’t see is the mind

directed by Love’s fletched radii,

nursed by Love’s growing diameter,

mastered by Love’s rigor,

braced by Love’s discipline,

tutored by Love’s grief.

One might be sympathetic to such visions of Love, and depending on your tolerance for devotional poetry, you may love or hate it.

For me, Lee is a much stronger elegist than he is a mystic. When he speaks of the dead, he is a poet. When he speaks of the beloved, he is an amateur mystic. (Lee himself laughs at his own mystical tendencies in poems like his 2008 “Standard Checklist for Amateur Mystics.”) Unfortunately, the mystic’s voice often drowns out the poet’s voice. In “The Herald’s Wand,” for example, lines like “Forget your ambitions / Bring your weeping” are followed by exclamations such as “Offspring of sacrifice! Descendent of the altar!” We begin to miss the younger poet who once kissed the blade after asking himself, “What then may I do / but cleave to what cleaves me.”

After all the wings inspired by Love, we long for the gravity of grief to bring us down to earth, as when Lee speaks with the dead, and asks himself in his father’s voice, “Tell me, has your love of the world survived / your knowledge of the world.” The dead father’s question is a poignant one, almost paradoxical in scope, delicately balanced between love and despair. On any given day, the answer might be yes or no. But pondering such a question, we are glad to walk with Li-Young Lee along his “grief-stricken paths of wisdom,” the same wisdom that reminds us, almost like a prayer, “The soul dies often. The body dies once.”

Published on November 26, 2024