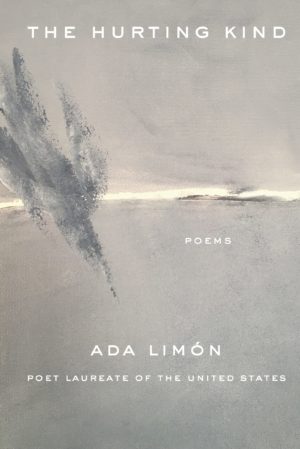

The Hurting Kind

by Ada Limón

reviewed by Kevin O’Connor

Critically acclaimed poet Ada Limón’s fourth book, Bright Dead Things (2015), broke through to a relatively large audience—and for good reason. In it, the future US Poet Laureate found a distinctive personal voice, one flexible enough to address topics as wide-ranging as coming of age, finding solace in nature, and witnessing the death of a close relative. Whether her poems express mourning, longing, or wonder, readers might feel as if they are having a conversation with Limón, albeit one delivered through sinuous, rhythmic syntax, in diction that’s at once informal and exact. Pivoting around the poet’s effort to bear a child, her next collection, The Carrying, recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award (2018), showed the suppleness of her free-form lyrics, equally capable of revealing nuances of feeling and dramatic epiphanies. “What if,” she writes, in “The Vulture & the Body,” “instead of carrying / a child, I am supposed to carry grief?”

In her new book, The Hurting Kind, Limón invites readers once again to share in revelatory moments as told from within an autobiographical context. But the force of this collection is more outward-facing, focusing especially on how we, as human beings, are interconnected with other natural phenomena (plants, animals, birds, distant stars), with each other, and with our ancestors. Although Limón is as clear-eyed as ever about loss and mortality, the book’s first poem, “Allow Me This,” announces the collection’s bright keynote: “Why am I not allowed / delight?”

The Hurting Kind is organized in four parts around the seasons, a schema that maintains the primacy of the natural cycle. These poems, in turn, attempt to move beyond personal epiphany, reimagining ways of regarding nature that aren’t egocentric: “Why / can’t I just love the flower for being a flower?” By interrogating her own need to domesticate and anthropomorphize nature through naming, Limón seeks not only to broaden the perspective of her poems, but to shift their trajectory. In “Drowning Creek,” the point of view moves with filmic seamlessness from the opening shot of environmental blight, to a close-up of a kingfisher, to a full-on reverse shot:

Past the strip malls and the power plants,

out of the holler, past Gun Bottom Road

and Brassfield and before Red Lick Creek,

there’s a stream called Drowning Creek where

I saw the prettiest bird I’d ever seen all year,

the belted kingfisher, crested in its Aegean

blue plumage, perched not on a high snag

but on a transmission wire, eyeing the creek

for crayfish, tadpoles and minnows.

Limón’s attempt to love the world more generously through acts of attention raises The Hurting Kind to a whole new level of ambition and achievement. “Privacy” (along with several other poems) would be considered an instant masterpiece if the poem did not so fully disavow the notion of masterpieces:

The crows seem enormous but only because

I am watching them too closely. They do not

care to be seen as symbols. A shake of the wing,

and both of them are gone. There was no message

given, no message I was asked to give, only their

great absence and my sad privacy

returning like the bracing, empty wind

on the black wet branches of the linden.

Limón is hardly the first to write a series of poems exploring the limits of lyric, but her quest is not just about escaping the self: it’s about training her attention on being itself and on rebalancing the reciprocal relationship between human witnesses and their natural environment. Instead of “superimposing / a face on flowers,” Limón wants to imagine a “less lazy kind of love” (“In the Shadow”). In “The Magnificent Frigatebird,” the poet divests herself of the power of naming altogether. Of the unfamiliar eponymous bird she writes:

I had never seen them before.

Eight feet wingspan and gigantic in their confident gliding, black,

with a red neck like a wound, or a hidden treasure. Or both.

When I looked it up, I learned it was the Magnificent Frigatebird.

But a few lines later she ventures, “I wondered if they named each other,” granting the frigate bird, like the crows in “Privacy,” some measure of autonomy from human representation. The girl initiated as a species predator in “The First Fish” becomes the speaker of “The Magnificent Frigatebird,” enraptured by this imaginative transfer of power.

In the book’s last section, “Winter,” Limón pushes back against the well-worn trope of cyclical dying. In “Lover,” a simple word is enough: “I trust the world to come back. / Return like a word, long forgotten and maligned.” But this section focuses mainly on other people as the source and proof of deep attachment. “Against Nostalgia,” “Forgiveness,” and “Heat” make up a series of moving love poems for a living person. Her meditative six-part title poem, “The Hurting Kind,” pays homage to Limón’s ancestors, especially her grandparents. In the poem’s conclusion, she deflects sentimentality with self-deprecating humor:

I see the tree above the grave and I think: I’m wearing

my heart on my leaves. My heart on my leaves.

Love ends. But what if it doesn’t?

Limón risks emotional transparency, even deliberate naiveté, to make the case for loving the world even as it breaks our hearts.

Published on October 11, 2022