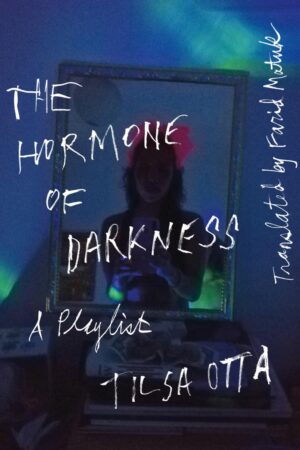

The Hormone of Darkness: A Playlist

by Tilsa Otta, translated by Farid Matuk

reviewed by Helen Quah

The Hormone of Darkness: A Playlist, translated from Spanish by Farid Matuk, is the first bilingual collection by the Peruvian multimedia artist Tilsa Otta. Like a curated selection of music, we are swept along by the surprises and emotional shifts of this funny, feverish, and often erotically charged compilation. Traversing four volumes of Otta’s work, the long sequences mixed with starkly short poems flow seamlessly, as if they’d always belonged to one organic system.

In the title poem, “The Hormone of Darkness” (La hormone de la oscuridad) we are told that “a nightclub doesn’t make a summer” and that the speaker believes more in “play everlasting / agitation of a critical mass.” Here, the hormone represents the excessive female erotic desire to claim more than is given to her:

I have three X chromosomes, but I want +

+++

I want the hormone of darkness

I want to see

who can open their mouth the most

who has the longest tongue

This daring reversal of the pornographic image of the female body into something embracing, calling for excess rather than control, is typical of this defiant collection. We have gone beyond a simple placing back and covering up of the female body. Instead, Otta wants to see, offering us the alternative vision where women reclaim their mouths, their chromosomes. She goes on in celebration as “our bodies / leak and we dance.” Her aspirations are visceral and clear in their transgressions, and all the more invigorating to read in this deft translation.

Hélène Cixous, in her famous essay “The Laugh of Medusa,” wrote that “woman must write herself: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies—for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal.” Otta may be the new woman. In a sense she has exceeded Cixous’s imagined gender limits and opted for an erotics of womanhood. Otta comments on the laws that kick her “out of this world” but is not defined by them; she remains triumphant and jubilant in the displacement. As a queer Latinx poet, she speaks to a sense of oppressed communities who are fighting back, not only surviving but flourishing in the dark. Here “death is a girl who heals with her hands.” In this subversion Otta aims at once to reposition and undermine the patriarchal and heteronormative realities, forcing us to contemplate new and reimagined lives, how far we should be willing to go to get them.

We’re never allowed to dwell in certainty for very long. In the poem “Dodge,” Otta moves through multiple dimensions, from the “space cemetery” to a lake to parking lots to dark cinemas before declaring:

when I first heard that woman is an object

I professed a bulletproof love of objects

my toys were everything and they were mine

your toys weren’t everything and they were also mine

The speaker is able to claim their toys as well as yours, an expansive ownership and reclamation through the act of love. She confronts the objectification of women’s bodies directly and claims the toys to undermine the patriarchal sense of ownership that is much like a child’s greed. Whole worlds are fleshed out and asserted throughout the collection, such as in the poem “The New Heaven.” Otta invites us to the heaven she has created. She has also invited Carl Sagan, Madame Blavatsky, and the girl from The Ring who is “selling cigarettes and mezcal.” Otta playfully challenges us to make sense of this ragtag group of historical and fictional figures. What kind of heaven could this be? Is this Otta’s lineage of influence, her collective? Either way, she is interested in stretching popular and literary culture to accommodate the stars as well as the “we nobodies who are happy too.” She wants us to expand our ideas of radical collective futures while hinting at the difficulties of this idealism when:

Suddenly all the dead have started looking for god and it’s created a silence on the

… terrestrial plain that’s total vaporwave

They’re in a frenzy going over the design

like there’s a prize to find

And though we’re already in heaven

They’re still at it!

Otta ironically pokes fun at the human need for a male god and leader to save them. Quickly moving on to accept their hugs and kisses as apology, she returns to adding “some cyclops over here and some little seahorses” to her transgressive utopia. She continues:

We can go on like that forever

building paradise from our urges

out of our fetishes our loves our vices

How lucky.

Otta’s paradise—and this collection—contains a sense of rebellious hope. This is not a descent into an underworld but rather an ascent of the gaze, looking up and outward into new spaces for the “nobodies” and the “folx”, the non-binary and previously abused communities. Otta pushes further than just a critical stance on these subjects. She bends and materializes them into her poems. In this new heaven she awaits us, urging, “don’t be too long.”

Published on January 22, 2025