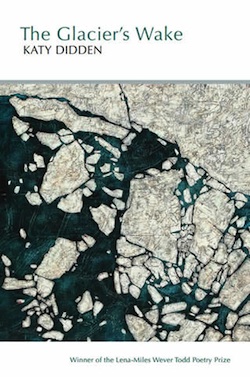

The Glacier’s Wake

by Katy Didden

reviewed by Julie Swarstad Johnson

In “The Winnowing of Wildness,” a 2004 article published in the Writer’s Chronicle, poet and essayist Beth Ann Fennelly argues that what first book contests ultimately reward is stylistic unity. Published a decade ago, Fennelly’s article continues to describe accurately the quality of contest-winning first books—not only unified in style, but often in theme or subject matter as well.

Fennelly worries about what the pressure to achieve this kind of coherence might do to a poet’s early work, but unity also has its virtues. Katy Didden’s debut collection The Glacier’s Wake, winner of the 2012 Lena-Miles Wever Todd Poetry Prize from Pleiades Press, presents one example of how this might play out. Grief over a father lost to leukemia provides an emotional through-line for the collection, but Didden broadens the book’s range by shuffling in poems spoken in the voices of elemental figures: the glacier, the sycamore, the wasp. Through the use of these repeating elements, Didden composes a cohesive yet varied first collection that considers a wide array of subjects even as it remains focused on longing and loss.

A 2013–14 Hodder Fellow at Princeton, Didden composes poems that meld personal experience with research, taking history, science, and art as places to begin inquiry. Some of the topics considered in The Glacier’s Wake include Ovid’s Pyramus and Thisbe, a Civil War balloonist, Renaissance painters, a sculpture at Chartres Cathedral—subjects which evoke the writing of Linda Bierds. Didden also echoes Bierds in her speakers. Take, for instance, Didden’s close third-person rendering of a craft-show clerk examining distant mountains in “Lamoille County Field Days”:

She stares

like she’ll be quizzed for details later, when she turns back

towards the fairgrounds, the whole town gathered there,

moving like a sugar-seeking river, like a sweaty sea

that barely registers when it shifts to make room for her.

Didden holds the reader at a distance from the poem’s central figure while rendering the scene in lush details, asking the reader to fill in the gaps that the poem leaves open.

A variety of narrative personae provide fresh avenues to the personal in Didden’s writing. Non-human voices consider human themes: the glacier speaks about aging, the sycamore about loss, the wasp about love and faith. Slipped between poems in which “My father’s secret // blood, cancered, starves / the body,” these poems often convey loss even more convincingly than their more conventionally narrated counterparts. “The Sycamore on Praise,” for example, presents grief and bitterness in an unexpected context: “Seeing death everywhere, you can choose / despair, blunt your roots on rocks, accuse / the cold wind as it lashes your limbs.” While these sentiments might fall flat in an ordinary poem about death, here they surprise because of their speaker. By mixing the personal and the alien, Didden’s poetry finds a wider emotional resonance.

Although these elemental figures help The Glacier’s Wake cohere, they also occasionally weaken it. Fennelly notes that one problem with overly cohesive first books is that sometimes “the poet substitutes not only better poems for weaker ones but also ones that fit for ones that don’t.” Here, the persona poems clearly function as structural elements, pillars to support the book’s emotional weight. In “The Sycamore on Praise,” they work beautifully, but in some cases, primarily the shorter pieces, they feel underdeveloped, lacking the rich details and earned insights of other poems. “The Glacier on Middle-Age,” for instance, concludes too quickly, “Your beauty is now up to you,” and in “The Sycamore on Forgiveness” wrath too easily gives way when “mercy schools you: green shoots / spring from the mess you mangled.” While these poems contribute structurally, they lack the revelations present elsewhere.

Still, The Glacier’s Wake achieves what it boldly sets out to do—Didden successfully mixes personal poems with poems that are carefully distanced from her life, and she assembles a collection that is both tightly woven and intellectually broad. Never overly obsessed with a single set of images, The Glacier’s Wake returns always to “a dark silence / and the great pull / we only understand as longing.” Through richly woven language, Didden succeeds in making that longing the reader’s own.

Published on June 26, 2014