The Book of Emma Reyes

by Emma Reyes, translated by Daniel Alarcón

reviewed by Cecilia Weddell

The Book of Emma Reyes found its translator, Daniel Alarcón, at the insistence of a pushy stranger. Alarcón describes the meeting in his translator’s introduction: “A stranger literally pressed it into my hands at the Bogotá Book Fair in 2014. ‘You must read this,’ she said. ‘You have to.’” Perhaps the stranger knew that those hands were those of a great finder of Latin American stories; as executive producer of the Spanish-language NPR podcast Radio Ambulante, Alarcón dedicates much of his time to unearthing and sharing well-told, moving stories from the Americas. Emma Reyes’s memoir, originally published in 2012 by the small Colombian press Laguna Libros, finds good company with the fascinating narratives offered by the Radio Ambulante podcast.

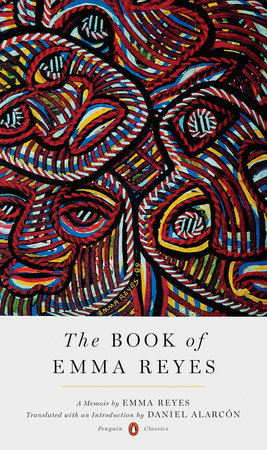

Before this memoir, Reyes was best known as a painter, a friend of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. What was known of her was her life in France, where she was (as Alarcón describes her) “a kind of godmother to Latin American artists and writers.” This book is the story of Emma Reyes before Europe—it is the memoir of the first nineteen years of her life, from her impoverished birth, to her abandonment by an indifferent mother, to her adolescent years in a restrictive convent.

The book’s history is as engrossing as the story it carries. Reyes’s memoir is a collection of twenty-three letters to the Colombian writer Germán Arciniegas, written over the span of nearly three decades. Arciniegas encouraged Reyes to write the story of her life, and because she found it difficult to organize her memories, he suggested she attempt it in letters to him. There was a break in the correspondence, however, that lasted more than twenty years, because Arciniegas shared some of the letters with the great Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez. Alarcón writes in the introduction: “Gabo telephoned Emma in Paris to tell her how much he’d enjoyed them, and she responded with fury. As she saw it, Arciniegas had betrayed their implicit agreement of confidentiality.” Reyes did eventually write to Arciniegas again in the 1990s, and in 1999, he compiled a manuscript out of her letters. It took more than a decade to find a publisher for the book, and by the time Laguna Libros took it on, both Arciniegas and Reyes had passed away.

“Emma was proud of her writing—not because it was good, but precisely because it wasn’t, at least not in a conventional sense,” Alarcón notes. Reyes’s writing is simple and straightforward, highly descriptive but never ornate. Her clear prose is laced with breathtaking truisms, expertly relayed in English by her translator. Recalling an early memory in which her baby brother is deliberately abandoned at a stranger’s doorstep, Reyes writes: “I clutched the weeds, contorting like a worm … I think I learned then, in that one moment, what injustice is, and that a child of four is already capable of feeling that they no longer want to live, that they should be swallowed up by the earth’s bowels.” Describing one of the few nuns who showed her kindness, Reyes states evenly: “For me, she represented all kinds of love and every shade of tenderness combined.” Declarations of sentiment like these, concise and powerful, characterize the memoir.

Reyes’s painter’s eye is evident in her precise descriptions of distant recollections. At one point, she addresses the clarity of her memories in an aside to Arciniegas:

You must think it strange that I can tell you in such detail and with such precision what happened so long ago. I agree with you, that a child of five who leads a normal life wouldn’t be able to recount his childhood with this level of accuracy. But we, [my sister] Helena and I, remember it as if it were today, and I can’t explain why. Nothing got by us, not the gestures, not the words, not the noises, not the colors. Everything was clear for us.

It is difficult not to feel affection for the writer of this story. Still, Reyes resists pity with her clear-eyed storytelling. Small touches of endearment within her letters speak directly to the reader, even if they are meant for Arciniegas: “A thousand memories and kisses. Write.” When she writes, at the end of Letter Number Eight, “I’m sad because this letter didn’t come out the way I would’ve hoped, but I don’t feel able to try again,” the honesty that shapes the memoir explicitly becomes part of the story.

The greatest disappointment of this book is that it ends before Reyes’s story ends. A nineteen-year-old Emma Reyes escapes from the convent without anyone noticing, and she stops outside: “Before moving further into the world, I realized it had been a long time since I was a girl.” The memoir ends on this nearly empty street outside the convent, and one wonders how such a street led to France, to painting, and to Reyes’s eventual friendship with artists and writers like Arciniegas and García Márquez. This last letter does not include one of Reyes’s characteristically loving sign-offs, but as the teenage Reyes stares out at her unknown future, a command written to her correspondent decades later resonates: “Kisses to the whole family, and don’t forget me.”

Published on August 21, 2017