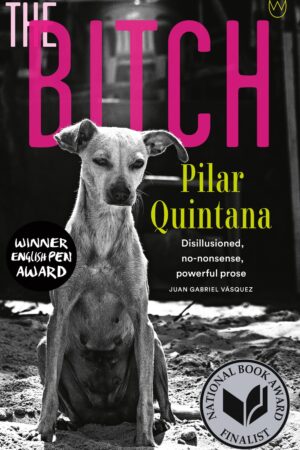

The Bitch

by Pilar Quintana, translated by Lisa Dillman

reviewed by Gabriel García Ochoa

The Bitch is Colombian author Pilar Quintana’s first work to be translated into English, a novella with some chapters of only a few hundred words. The plot centers around Damaris, who lives in a coastal town in Colombia and is married to Rogelio, a fisherman with a temper. Despite their best efforts, the couple have failed to have children. When Damaris adopts a puppy from her friend Doña Elodia, she becomes fiercely protective of the dog, transferring her dreams of a mother-daughter relationship to the pet. Damaris even gives the dog the name she had intended for her first daughter: Chirli (a Spanish transliteration of Shirley).

As Damaris tries to grow closer to Chirli, her expectations of her bond with the dog are not met. Far from the noble, loyal pet Damaris longed for, Chirli has a propensity for independence, which Damaris interprets as disregard. Sometimes she goes wandering in the jungle for days on end, leaving Damaris to worry about her whereabouts. Worse, Chirli is particularly fecund but has no interest in her puppies. Soon after delivering her first litter, she abandons them to “go lie in the sun by the pool or sprawl in the washtub, where it was always cool, or under one of the houses with the other dogs.” She even eats one of them. For Damaris, this “disdain” of motherhood feels like a betrayal, Chirli throwing Damaris’s dreams in her face. Damaris grows jealous and resentful of Chirli. This is ridiculous, of course, but Quintana makes it both heart-wrenching and plausible.

As a story about dogs and their owners, The Bitch is much more Amores Perros than Marley and Me. The book delves into societal pressures, particularly those brought about by gender roles, and how such pressures can be internalized—as failed personal expectations, guilt, profound dissatisfaction, and violence.

While Chirli subverts the expectations of motherhood, the setting of the story subverts expectations of “natural beauty” and so almost becomes an additional character—reminiscent of Wuthering Heights. To supplement their meagre income, Damaris and Rogelio live in, and look after, the home of the Reyeses: a shack close to the cliffs, overlooking the ocean and surrounded by jungle. Here, nature, the ocean, and the jungle are merciless and murderous; they swallow people whole. This is the perfect atmosphere for mothers to be killers, and killers to be kind.

Like the themes it explores, Quintana’s prose is stark and somewhat grim. Consider this passage on Mosco, one of Rogelio’s dogs, who had a wound on his tail: “By the time Damaris and Rogelio took any notice of it, the wound was full of maggots and Damaris thought she saw a mosca–a fully formed fly–flutter out of it.” To remedy the situation Rogelio “grabbed the end of the dog’s tail, raised his machete, and before Damaris realized what he was doing lopped it off in one go.”

Lisa Dillman does a very good job delivering Quintana’s stark prose. I have discussed Dillman’s translations before, for this and other publications. Dillman is a seasoned translator, and overall Quintana’s novella reads well. However, there are moments when the text falls short of what I have previously called Dillman’s “heroic” work. Take, for example, the following sentence: “At one point, Damaris got trapped in front of Ximena’s spot, which was much nicer than those of the indigenous.”

Here, we see a direct translation of a sentence structure that works well in Spanish, but not in English. In Spanish, adjectives can commonly be used as nouns. Such is the case with the word indígenas—“indigenous”—which, in this case, refers to indigenous people. Because the switch from adjective to noun is much less common in English, placing the word “indigenous” at the end of the sentence feels less smooth and natural than it would in the original work (there are a few examples like this in the book). Focusing on a word or a turn or phrase out of tens of thousands is probably petty, but hard to avoid given the high standards, and thus expectations, that Dillman has set with her prior work. Flaws like these make the translation feel rushed at times. This may also have to do with the length of the book; in a short novella such flaws are more prominent, while they can easily go unnoticed in a larger work. Regardless, Quintana’s book is an engrossing, engaging read that can be enjoyed over a few hours, and one of the best examples of Wendepunkt—an unexpected turn of events—I have come across in a very long time.

Published on December 22, 2020