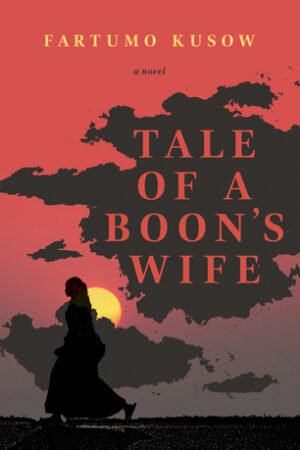

Tale of a Boon’s Wife

by Fartumo Kusow

reviewed by Leena Soman

Tale of a Boon’s Wife is the story of Idil, a young woman who comes of age in the decade leading up to the Somali Civil War. As a member of the dominant Bliss tribe and the daughter of a Somali general, Idil lives a life of abundance. When her father takes a mistress, her mother becomes obsessed with saving him from the seductions of other women, fearing for her own reputation in a community that blames wives for their husbands’ infidelities. The family moves to a new city, where Idil falls for a classmate, Sidow, but her mother forbids their relationship given his Boon tribe’s subordinate status. Idil and Sidow elope, and her family’s ensuing malfeasance not only disrupts her domestic life, but also exacerbates Somalia’s state conflict. Fartumo Kusow writes Idil’s journey from naïve girl to intrepid wife, mother, and survivor with graceful strokes, and the novel is at turns harrowing, heartbreaking, and ultimately hopeful.

The beginning of the book considers the layers of burden women in Somali society face, even the most privileged among them. After marrying Sidow and moving to his ancestral farmland, Idil has no trouble adjusting to simpler, poorer, village life—a welcome reversal of expectations. Her act of courage involves defying her family’s wishes for her future, rather than standing up to the political misdeeds they perpetrate against civil society. Marrying a Boon against her parents’ wishes is an act done in her own interest, not a crusade to protect others from her family’s malice. After learning about her father and brother’s plots—ranging from grabbing ancestral Boon lands to distributing illicit drugs—she is more than willing to renounce her family, but she has no hope that she can stop them. The best she can do is run away and separate herself from their crimes. Hemmed in by the limits of a woman’s role, she is more like her mother than she suspects, even though, as a youngster, she denounces her mother’s choices. Idil embodies the notion that the personal is political. “‘A man’s dirt is his woman’s wash, always,’” her mother warns.

Though Idil is well-drawn, the other characters suffer from a lack of nuance. Idil’s older brother Omar is evil incarnate; as a child, he enjoys torturing animals and only grows worse. Elmi, Idil’s younger brother, is his foil: sensitive, perceptive, and compassionate. These two and others feel more like types than fully realized characters. Idil’s father is the epitome of an iron-fisted military leader. Celebrated Somali writer Nuruddin Farah once said, “Study the structure of the Somali family and you will find mini-dictators imposing their will.” Perhaps the static nature of the secondary characters is deliberate, a technique Kusow employs to highlight other story elements.

What the book lacks in character development, it makes up for in pacing. The story moves at a fast clip without sacrificing depth. While Kusow’s language is lyrical, the author does not dwell on description. She offers a few telling details to ground the reader in Idil’s point of view while advancing the narrative. “I rose from the bed, lightheaded and feeling the magnitude of the decision I was about to act upon,” Idil states of her elopement. Of the consummation of her marriage on her wedding night, Idil says,

We didn’t leave the hall until all the guests were gone and the tables and decorations were stored away. A sense of happiness washed over me as we walked home openly as a couple. Alone in our bedroom, I kissed Sidow with passion, “I loved everything about our wedding party,” I said.

“Everything?”

I nodded and kissed him again, long and deep. After our love-making, I fell asleep listening to the happy laughter of the guests and seeing the dancers in my head.

The relative pleasantries of the first half of the book—Idil’s school days and falling in love with Sidow—give way to intense episodes of violence and trauma in the second half. Though some say that experiencing greater oppression can enable the best art, the author understands how such a notion presupposes survival, a privileged state all its own. Writing Idil’s journey toward self-determination against the political backdrop of a failing Somali state, Kusow deftly handles difficult issues such as rape and domestic abuse amid the devastation of Civil War. Toward the end of the novel, during an interview at a refugee camp in Kenya, Idil tells an official the story of the violence she and her family survived prior to arriving. “The man didn’t flinch,” she observes. “The stories he heard in these interviews must have made it impossible for anything to surprise him. For a fleeting second I felt sorry for him. It was painful to tell my dreadful tale, but what must it be like to receive such tales daily and document the horror?”

Though geographically distinct, in Tale of a Boon’s Wife Kusow explores terrain similar to Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West: the way a city or community teeters on a precipice for a time before descending into chaos and the way young lovers can go from thinking about their future together to thinking about basic security and survival in a matter of weeks, if not days. WithTale of a Boon’s Wife, Kusow contributes a strong story to the body of contemporary literature giving voice to the lives of immigrants and refugees.

Published on January 4, 2018