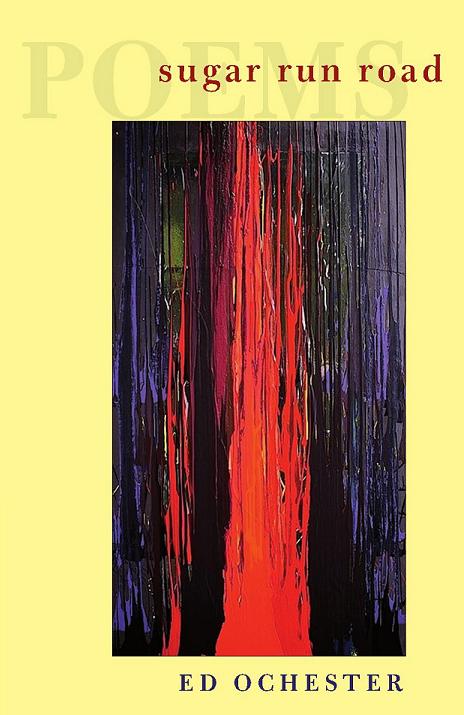

Sugar Run Road

by Ed Ochester

reviewed by Chard deNiord

In his famous paradoxical definition of “negative capability,” John Keats wrote to his brother George in 1817 that the quality that “struck” him as particularly important for forming “a Man of Achievement, especially in literature,” was his capability of “being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Throughout his long career, Ed Ochester has cultivated his own humorous negative capability with an irreverent wit that flows as easily off his tongue as it does his pages. But there is an element of pathos, too, in Ochester’s poems that balances his satirical verses with plainspoken sympathy for his fellow fallible subjects—largely archetypal ordinary folks from the purlieus of America, but also such historical and literary figures as J.D. Salinger, D.H. Lawrence, Henry Frick, Catullus, Andrew Carnegie, Gertrude Stein, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Johann Goldberg.

In his latest book, Sugar Run Road, Ochester pays tribute to perhaps his most abiding influence, the Roman poet Martial, by writing this brief ars poetica within his poem “riding westward”:

I like complexity, not confusion

plain surface texture

free of mere complicatedness and

remember what Martial wrote

2000 years ago at the grave

of a five year old child:earth weigh lightly

on her slight bones

she whose footsteps

barely touched the ground

The tender allusion Ochester makes to an epigraph by Martial at the conclusion of this poem captures his complexity, his incisive satire, and his plainspoken pathos. But it’s sweetness that wins out in his poems, no matter how biting they may be, which may be why he titled this book Sugar Run Road. Having studied under such self-effacing contemporary masters as James Wright, Ethridge Knight, and Edward Field, Ochester found his own voice several decades ago, one with parody and pathos, candor and compassion—a seasoned yawping that resonates throughout Sugar Run Road. In a poem about his uncle Frank, for instance, he combines literary and vernacular language with seamless mastery.

What can I tell you?

Frank was a plain man, a truck driver,

who loved me and was always kind.

He never read poetry—surely not Yeats—

and would have been surprised to hear

that love will pitch its tent

in the very place of excrement.

Ochester likes to make fun, but never without including himself as one of the crowd he’s satirizing. This parallax vision, in which he has one eye on his subject and the other on himself as self-implicated member/victim of what he likes to call “American dumb fuckism,” guides him from poem to poem, instilling his voice with a deceptive profundity that entertains and witnesses at the same time. Like many of his subjects, Ochester grasps that the truth about those he places before him can’t be told from the perspective of the erudite poet-critic (although he is remarkably erudite when he wants to be), but rather from the point of view of one of his subjects. He falls in love, therefore, like James Wright, with “the dumb fucks” who populate his poetry. It’s an endearing, effective strategy. The bittersweet, quotidian stories he tells about librarians, cops, his mother, his grandchildren, and other poets (Gerald Stern, Ross Gay, Michael Waters, and Afaa Weaver) derive from the uncertainty Ochester immerses himself in as an undercover poet with satirical acumen.

Writing willfully against indeterminacy as a pedestrian witness to American life, Ochester milks memorable little things out of daily encounters in ways that seem perhaps too facile at first but stay with you, as in this recalled encounter with a Boston cop who took his “intro to lit” night course at Boston University:

An older Irish cop

kindly told me after class:You gotta remember

“these guys never had no advantages”

and

“that Hahvard book bag,

it kinda makes you look like a fag.”

Ochester wisely respects his reader’s intelligence. His satirical conceits, as well as his plainspoken elegies and tributes, depend on it.

These are wonderfully raw yet refined poems that negotiate the fine line between plain speech and memorable written expression. Ochester has labored for years in the vineyards of working-class America, while also serving as editor of the University of Pittsburgh Press Poetry Series. Indeed, he has quietly achieved a well-deserved reputation as a rare double threat in American letters in his capacities as a strong poet and a skilled editor. The poems in Sugar Run Road only serve to enhance his stature as a vital witness to a desultory, essential array of American voices in the crowd.

Published on October 18, 2016