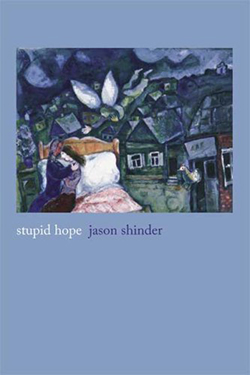

Stupid Hope

by Jason Shinder

reviewed by Adam Eaglin

When Jason Shinder lost his battle with lymphoma and leukemia in April 2008 at the age of 52, he was perhaps better known as a teacher, editor, and advocate for poetry, than as a poet himself. This is not to diminish his first two volumes, but more to recognize the scope of his work as poetry’s supporter. Shinder founded and directed the YMCA National Writer’s Voice, taught in graduate writing programs at the New School and Bennington College, and edited numerous anthologies, including The Poem That Changed America: “Howl” Fifty Years Later, a collection to which Shinder had a personal connection as a former apprentice to Allen Ginsberg.

In addition to his legacy among students and readers, Shinder also left behind pages and pages of uncollected and (in many cases) unpublished poems. His four literary executors (Sophie Cabot Black, Marie Howe, Lucie Brock-Broido, and Tony Hoagland) lovingly pored over these poems, eventually sorting them into the work that would become Shinder’s best book—a third, final, and devastating collection about the poet’s discovery of his illness and what came after. Here, in its entirety, the poem “Afterwards”:

I remember the shame I felt after the news

of the illness that I was not as lovable

as I thought. I must have done something

wrong. And then

I was content in my disappointment

which kept me alone. It was a kind of courage

that allowed me to go on without comfort.

It was a kind of beauty when there was no one

I wanted near.

Every poet, perhaps every writer, confronts the notion of death in some form, be it literal or philosophical, self-referential or tangential, but I can’t recall a book that addresses mortality with such brutal self-awareness, in such plain language, with such a complete lack of sentimentalism. The poems can be at once exuberant and despairing, all told in this casual rhetoric.

The book’s arc begins with the deteriorating health of the poet’s mother before he learns of his own (unrelated) illness, and the book opens with the Hindu proverb, “No disease like hope.” This idea recurs in the poem “Living,” as brother and sister sit with their sick mother in the hospital:

And then, with her eyes closed, my mother said

the one or two words the living have for gratefulness;

which is a kind of forgetting, with a sense

of what it means to be alive long enough

to love someone: Thank you, she said. As for me,

I didn’t care how her voice suddenly seemed low

and kind, or what failures and triumphs

of the body and spirit brought her to that point—

just that it sounded like hope, stupid hope.

In his first two collections, Every Room We Ever Slept In (1993) and Among Women (2001), Shinder wrote plainspoken verse about desire, city life, self-discovery. The writing was unadorned, with a sort of Zen-like frankness. That lack of artifice didn’t always work, but there were glimpses of insight.

While the mode is similar here, the effect is utterly different. Post-diagnosis, Shinder’s spare stanzas (one or two lines long, with varying line lengths) detail the decay of the body, the despair and then calm acceptance of the mind, and, ultimately, a clarity that allows the poet to contemplate living just as much as death. Shinder’s lineation is delicate and subtle, often pulling one sentence through the entirety of a poem, breaking it up with frequent line breaks and pauses, heightening and then slowing down the tension.

Stupid Hope has been called a worthy contribution to the literature of illness (which it is), but it continues themes of Shinder’s oeuvre, like sexual desire, which, as it relates to the body, accumulates new layers of meaning and association. “I’m becoming more like my father: I rarely have sex,” he writes.

But the book is just as much about memory, how we process it and keep it sacred, even though it must always remain separate and uncertain. “I want a door opening in me that I can enter / and feel the clarity of evening and the stars beginning,” he writes in the book’s final poem. “One after another, I want my mistakes returning and to approach them on a beach like a man… / Not everything is given and it should not permit sadness. / Let me / Let me keep on describing things to be sure they happened.”

The poems can be difficult, even terrifying, but the book rewards reading from cover to cover. It’s not all despair, and I’m sure Shinder would not have wanted it to be perceived that way:

…the woman reading the poem,

in the silence between the words,

in her kitchen, filled with a gold, metallic light,

finds the experience of living in that moment

so clearly described as to make her feel finally known

by someone—and every time the poem is read,

no matter her situation or her age,

this is more or less what happens.

Published on June 20, 2013