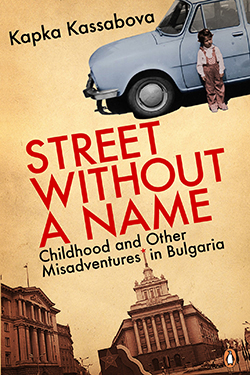

Street without a Name: Childhood and Other Misadventures in Bulgaria

by Kapka Kassabova

reviewed by Carmen Bugan

It is now over twenty years since the Berlin Wall was brought down in November 1989, an event which brought “us” and “them”—depending on which side of the Wall one lived on—together. With the reluctant admission of Romania and Bulgaria to the European Union in 2007, East and West are coming face-to-face more often, not always in the best of ways. This is why stories of exile, wandering, and of emigrants’ relationships with their homelands are the necessary links between the West and the old East.

Kapka Kassabova’s memoir reads like a travel guide to Bulgaria before and after the fall of communism there in 1989, but it is also a personal search for a lost childhood in a lost country. Her lucid narrative, conversational tone, and outbursts of poetic description bring a fresh voice to contemporary European literature. Street without a Name is a compelling read for anyone who wants to know more about Bulgaria, about the new face of Eastern Europe, and about the lifelong preoccupation of the immigrant with a sense of place.

The book begins with the story of Kassabova’s childhood on the outskirts of Sofia, relating in memorable detail how her parents, engineers by profession, spent much of their time trying to make the best of a stressful, deprived existence. Her first visit to the Berlin Wall at the height of communism, instead of awakening in her a sense of the world being divided, made her feel as if she were in a familiar place. She describes this experience with the gravity of someone who has endured tremendous privations. “Like most people on our side, I had internalised oppression. The Wall was already inside me, the bricks and mortar of my eleven-year-old self. The Wall wasn’t a place or even a symbol any more. It was a collective state of mind, and there is something cosy, something reassuring in all things collective. Even a prison.”

One particularly memorable segment from this section of the book concerns a visit to Holland by the author’s parents. During a trip to a department store, the couple was “overcome by [an] orgy of abundance.” They had experienced huge privation on their side of the Wall and were stunned by the surplus and waste on the other. With their world turned upside down by this show of inequality, of which they had until then been utterly oblivious, they returned to Bulgaria feeling doubly cheated. Kassabova describes their predicament thus: “It was almost as if my parents had traded something in, as if they had crossed some Styx to reach a mythical land, and brought back otherworldly gifts. But in return they had left behind their shadows.” Street without a Name reveals exactly this kind of view of the world—the view of plenty through the eyes of the deprived, which invests the notions of poverty and wealth with a personal, psychological dimension.

When the Berlin Wall came down, and with it the communist leadership in Bulgaria, the family was keen to get as far away as possible. They went first to England and then all the way to New Zealand. Writes Kassabova: “In 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I left Sofia for Britain, New Zealand, and again Britain, occasionally stopping in France and Germany for a year or so. In the process, I acquired lots of visas, one passport, some half-wasted lives, and an impressive collection of delusions.” This story of emigration and intermittent return occupies roughly the second part of the book, which is written as a travelogue. Kassabova tours Bulgaria, stopping briefly at places she remembers from childhood, recounts historical anecdotes, and observes disconsolately that the country has become prey to greedy investors while local people mourn the passing of socialism.

But what is most impressive about this second half is the sense of deracination presented as restlessness, the constant need to go back and forth to Bulgaria without being able to articulate exactly what is missing from life. Who knows how many immigrants have returned to the countries of their birth only to find themselves strangers, their memories of the old home battling with the new, post-communist reality? Kassabova’s sense of humor makes the narrative of old and new Bulgaria, as seen through the eyes of a sometimes detached, sometimes emotional emigrant, readable and enjoyable. But for those who live as exiles, emigrants, and refugees, hers is a book that speaks deeply of the relationship between people and their land, a relationship broken by totalitarianism and the consequent emigration.

Published on June 20, 2013