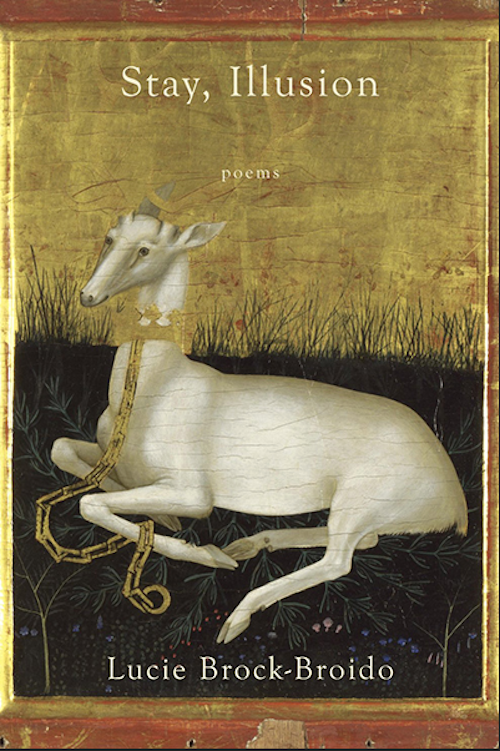

Stay, Illusion

by Lucie Brock-Broido

reviewed by Joelle Biele

Lucie Brock-Broido’s latest collection of poems, Stay, Illusion, offers a sweeping look at death. In elegies sophisticated and sumptuous, she reflects on the suffering of loved ones and the final moments of cultural figures as varied as Osip Mandelstam and Tookie Williams. Ragged lines and fragmented stanzas teem with images from what she once called, her “impossible post- / Raphaelite world”: the broken bodies of slaughtered animals and the autopsies of suicides juxtaposed with delicate folds of cashmere, linen, and silk. Contemplative and knowing, conscious of her own mortality, the speaker raises more questions than she answers. These are lyrics pushed to the very edge of sense.

The speaker’s commanding presence can be traced back to Brock-Broido’s first book, A Hunger (1988). Full of persona poems in the voices of vulnerable children and violent outsiders, it focused on speakers in heightened situations who were often unaware that they might be on the verge of their own deaths. In Stay, Illusion, Brock-Broido has exchanged the dramatic monologue for the apostrophe and cut her poems down to nearly a quarter of their former size but she has maintained their high stakes. She summarizes her work this way:

Her single subject the idea that every single thing she loves

Will (perhaps tomorrow) die.

High editorial illusion of “control.”

By abandoning anything close to exposition, Brock-Broido relies on recurring private symbols and ample white space to hold her narrative together. The result is difficult, intimate silences and arresting, sensuous lines. Writing about the childhood loss of her father, a dying friend whose “willowing” hair suggests Rossetti’s “Ophelia,” and another’s cut-open body with “ten thousand rags of music” in his “thoracic cavity,” it’s the tension between the speaker’s authoritative tone and her hints of self-doubt that keep the reader moving down the page.

Brock-Broido’s poems invite the reader into their velvet-draped rooms—the “abandonarium” and “trepidarium”—to luxuriate in language, in “gauze and glossolalia.” A note to sentence-diagrammers and wielders of blue pencils: these poems are meant to be heard. Their formal, sometimes brocaded diction is awash in sonic effects that create the feeling of a nagging helplessness and an acceptance of ruin. The speaker’s dead are not gone. “No matter what time it was, I will go on missing you again.” Single lines make multiple changes in tense or case—“Please to find a goddamn other noun. Lie down in it; stay here”—while others end with what looks like a noun only to reveal itself as the beginning of a metaphor when the next sentence starts—“How dare you come home from your factory / Of autumns.” Pronouns are sometimes missing antecedents and spliced clauses can potentially modify both the subject and object or some unnamed thing altogether as a way of enacting the shifting potentiality of meaning.

What tempers the book’s language play is the speaker’s self-awareness, the disquiet in the occasional remarks about her poetry, and the implications of her images. After a particularly grizzly portrayal of newborn cats, she says in “Dear Shadows,” “I could barely stand to write what I just wrote now.” But write it she must. For the speaker, writing expresses the fear of “Not being in this world or in this world enough.” It becomes a way to fight mortality even as the words, she says, are running out. Calling up Marilyn Monroe in a poem that takes its title from the 1961 Arthur Miller film The Misfits, the speaker compares herself to both Monroe’s character, who understood the meaning of the wild mustang round up too late, as well as a roped and struggling horse. Monroe misreads the situation and in a desperate attempt to save the rearing animal seals its fate. (The film was Monroe’s last.) Likewise, the speaker worries her work has been for naught.

I cringe to think I stood for nothing, for a jar

Of jam and marriages, my use of exotic words (chimerical), my lilac apron, me

Starry in our own home-movie, handsome, noir

As the one dark brooding stallion, kicking going down.

It’s a startling admission, the anxiety that one’s poetry may be “extreme wisteria,” “ivory hillocks,” a “toy / Pram filled with slippery mice,” “mares fetlock-deep in squalls / Of snow.” The realization may be shattering, but it doesn’t mean she’ll stop writing. The speaker’s future tombstone reads, “She Couldn’t Help It, Pals.” Language’s power to fend off the inevitable is a necessary illusion. The speaker is pushing against death the way she knows how, by “scribbling / Beneath her white uncorseted umbrella in the first draft of an early fall.”

Published on February 27, 2014