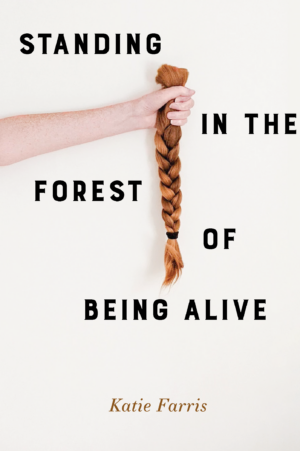

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive

by Katie Farris

reviewed by Kimberly Ann Priest

“Dem bones, dem bones, dem dry bones,” I used to sing in my childhood, rattling my body like a skeleton to mimic Ezekiel’s words. Reading Katie Farris’s Standing in the Forest of Being Alive is like reading the autobiography of those bones before their skin has been sloughed off, before they “strip and fold / [their] clothes into a bag, surrender” (“On the Morning of the Port Surgery”). There’s a ghost in those bones, a full life lived, that must wander the land of the living contemplating “[t]his elastic earth: / with little ceremony / how it expands,” and how “a grave / is a door / we open.” And there, at its threshold, Farris describes how we:

lay our dead down in,

begging

like a key begsa keyhole—

(“Woman with Amputated Breast at her Mother-in-Law’s Grave”). The speaker of these poems is going through the motions of eradicating the cancer in her breasts, waiting to know if she too will become dem dry bones, having lost all breath and dignity, let down through a keyhole guarded by the earth’s sod door.

Farris, author of boysgirls (2011), as well as the chapbooks A Net to Catch My Body in its Weaving (winner of the 2021 Chad Walsh Poetry Award), Mother Superior in Hell (2019) and Thirteen Intimacies (2017), calls Standing in the Forest “a memoir in poems.” In this poem-memoir, Farris writes centripetally from the rim of hope to the loci of fear. Romance and wit, bone scans, chemo, her lover’s gout, “[u]gly gardenias and muggy / sunsets, horizon glowing orange as a riot: all of these” Farris endures, training herself to look for, “in the midst of hell, what isn’t hell” (“The Wheel”).

Memoir though they may be, these poems are breathy and roomy, a tickle up the spine, resembling in their ache and humor all that I appreciate about Japanese haiku: how saying little can say so much, and how a metaphor happens through keen observation. In a short stanza from “Emiloma: A Riddle & an Answer,” Farris signals the absence of her breasts in just a few lines without speaking of absence at all:

Will you be

my death, Emily?

Today I placed

your collected poems

over my breast, my heart

knocking fast

on your front cover.

Here, Emily Dickinson’s poems rest upon the poet’s chest where, unobstructed by her mammary glands, they thrum directly against her beating heart. Clean, sharp, swift, Farris says exactly enough for a reader to vividly imagine her meaning.

In her poem “In the Event of my Death,” a single line about her cat evokes a shared grief. “In solidarity with my first chemotherapy,” she says, “our cat leaves her whiskers on / the hardwood floor.” And then there is “If Marriage,” one of the shortest poems in the book which, in its entirety, hints at indecencies shared and celebrated between lovers:

If marriage

is a series

of increasing

intimacies, a slow

sweet collapse into

oneness, I

would still beg

your forgiveness

for asking

your assistance

unwinding that pale hair

from my hemorrhoid.

At first read, I wanted the book to do more and say more, but then I read again and decided, no, this is perfect. Perfect like haiku. Farris musters all the energy she can through chemo, scans, surgery, and “pollen or seeds.” In the final poem, “What Would Root,” Farris rests her body against the earth as it becomes a tree mooring her. “[I]t was May [and] … I could see everything,” she says, “everything smelled green … a twig emerging, and another … that they were a part of my body I could not doubt … living and enervated and jutting out.” She continues, “the twigs / tasted sunlight with my mouth, the roots drew the salt / from my sweat into a vacuum.”

No dry desert bones are to be found here. These bones live, one way or another, on this earth, in her lover’s joy and memory, through these poems.

Published on July 18, 2023