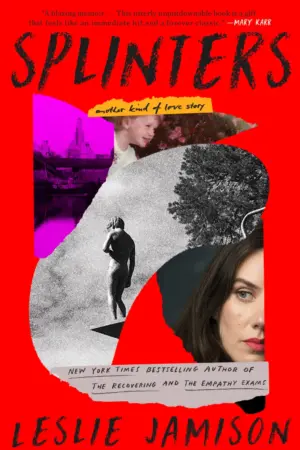

Splinters

by Leslie Jamison

reviewed by Liv Albright

Leslie Jamison’s new memoir, Splinters, explores the many facets of womanhood and its author’s competing desires as a wife, artist, and mother. In Splinters, Jamison details her struggle to find equilibrium as a career-focused mother, attending to her daughter’s needs while still creating art and satisfying her own romantic desires.

Jamison’s previous publications include a novel, The Gin Closet, as well as The Empathy Exams, The Recovering, and Make It Scream, Make It Burn—nonfiction accounts that combine the personal essay, literary biography, and reportage. Splinters, by contrast, is Jamison’s first “straight” memoir. Here, Jamison touches on crucial problems confronting mothers. Much of the ground she covers is well trodden. From a young age, Jamison writes, she struggled to ignore the impulse to modify her speech and her silences to impress the men around her—a fact of life many of her female readers can relate to. Jamison writes of her tumultuous relationship with her philandering father, who declined custody of Jamison and her older brothers, leaving them to their mother’s care.

When Jamison files for divorce from her husband C, a recent widower, it brings up longstanding feelings of rejection. As she exits her toxic marriage, she also gains a newfound sense of self-respect. Like her father, C is hypercritical of Jamison, judging her social behavior as “the elaborate puppetry of a woman desperate for everyone to find her kind.” Despite C’s disdain, Jamison paints him in his multiplicity, as playful and authentic, a hardworking father who wears his emotions on his face. Elsewhere, however, Jamison’s narrative feels one-sided. She describes herself as the tearful victim, cowering in the face of C’s grief-stricken insults. When Jamison dissects C’s mistakes—at one point he calls her an “anorexic bitch”—readers are disinclined to trust her motives, since nothing is said of her contribution to the marriage’s demise.

Interspersed throughout are Jamison’s descriptions of the everyday life of a new mother, written with a linguistic agility that veers into distractingly flowery language (“a blood clot … was the size of an avocado, jiggling like jelly”). Jamison explores the quotidian: pushing her daughter around the Brooklyn Museum in her stroller, spending time with writer friends at the Turkish Baths, and penning uncomfortably vivid (and frequent) descriptions of her nipples and breasts.

Readers may well wonder, given Jamison’s privilege, why she was the author to write this book. What saves these sections is Jamison’s deft ability to connect her experiences of motherhood to the New York art scene. At the Brooklyn Museum, Jamison encounters the work of Judy Chicago and Marina Abramovic, two artists who have expressed that having kids would have hampered their careers. Jamison then appears to show that she can have it all, as a mother, artist, and professor. She speaks at graduation ceremonies with her baby on her hip, teaches classes in her apartment while her daughter crawls inside the class circle, and, inevitably, gets covered in her daughter’s poop as a plane lands in one of the cities where her book is touring.

Although Jamison has professional success, her interactions with men seesaw from passive to proactive as she finds her professional footing. At a book festival where Jamison is invited to speak, she and her female colleague are paid less than the male speakers. Instead of attempting to remedy the situation, Jamison submits to it. However, when Jamison’s well-being is involved, she takes a stand. A pivotal scene involves Jamison asking a male professor to give her use of a shared office space so that she can use her breast pump. Unfortunately, these feminist scenes are scattered among commonplace descriptions of her daughter and Jamison’s mixed feelings about her, which repeat what has already been said rather than offering new insights.

What really makes these chronicles of a new mother tolerable is Jamison’s dalliance with her post-C love interest, a musician. Jamison’s depictions of him break up the banality of the mother narrative and echo a tactic Jamison uses in her Bible-sized hybrid memoir, The Recovering. In that book, Jamison interweaves her own narrative with those of celebrated literary addicts, placing a traditional story of addiction and recovery against the backdrop of legends, in an attempt to elevate her otherwise typical narrative. Similarly, in Splinters, without Jamison’s black-clad, tatted-up love interests to shake things up, the narrative content isn’t compelling enough to hold the attention of a diverse audience.

Jamison writes, “Twelve-step recovery had already taught me that everything I’d lived had been lived before.” The same is true of motherhood. Many of us are mothers, but not all of us have the opportunity to date a (possibly famous) 6’5” musician who has self-inflicted scars on his arms. Like many a woman faced with a hot, troubled artist, she thinks she can fix him. Jamison acknowledges that her infatuation with him may partly be about inhabiting the role of a musician touring the world to share his art. She craves the possibility of living freely, unencumbered by a baby daughter. But, like her ex, C, Jamison’s musician appears stuck in his teenage years.

Can Jamison find a way to enjoy freedom without the companionship of a destructive man? Will art, writing, and friendship offer enough of an escape from her maternal responsibilities? Splinters suggests that there are many possible forms of escape: book touring, sex, teaching, writing, and, perhaps, getting lost in reading picture books to one’s daughter. But none of that makes Splinters any less monotonous.

Published on January 23, 2024