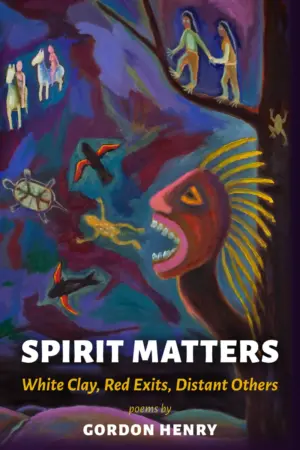

Spirit Matters: White Clay, Red Exits, Distant Others

by Gordon Henry

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Gordon Henry, an American Book Award–winning author and member of the White Earth Anishinaabe Nation in Minnesota, worked for fifteen years on his second collection of poems. With Spirit Matters: White Clay, Red Exits, Distant Others, he connects powerfully to the voices and traditions of his ancestors, bringing them to bear on contemporary life on and off the reservation.

In the prologue to Spirit Matters, Henry introduces Chiaaboos, an Ojibwe mythical figure who sat for years on the riverbank trying to commune with the dead.

Yes water’s edge may give you a song

And cedar another breath of prayer

But don’t forget the shadows as sun

Goes down in flicker fall of sparrows

Chiaaboos’s patience and persistence frustrated and impressed his people. Acting as a modern-day Chiaaboos, a woman phones her dead father

underground in a funeral shadow box

surrounded by liquor glass a few jagged

bottle bottoms, throats broken from empties,

the rest crushed stars of ice, brown grain

belt toenails, curved claws of windshield

glass blown open from some long night

of lost impact, an abused blue Buick

carrying a body heading for the star

road afterlies, afterlife

The starry destination of “afterlies, afterlife” expresses Henry’s wry view of immortality. The very title of the collection, Spirit Matters, encapsulates a dualistic paradox, and the poems chronicle earthly woes: guns, booze, sickness, violence, car wrecks. In an effort to rise above this suffering, his characters embrace a range of Christian, Native American, and secular beliefs, whether rosaries pulled from a wall before a card game, “Basketball floors set up for wakes,” or “a turtle mountain healing song / … transmitted by / towers and satellites.”

It is, however, the Indigenous spiritual journeys that lead, elude, and find us again, in extraordinary conversations and letters between people, ghosts, mythological animals, and visionaries like Crow Woman, Zahquod, and Venus Zhaawanigiizhik. Henry also uses characters such as Cousin X and Uncle X, named in honor of an ancestor who signed a treaty with the letter “X,” to embark on a postcolonial search for identity.

As for you Uncle X

Stone will carry

your name and let

it lie just this side

of that old spirit house

under the long standing

pine

In many of these image-embroidered, tautly phrased poems, Henry suspends conventional punctuation, capitalization, and syntax, while maintaining a graceful musicality. There are various personae, yet we often hear a soft-spoken speaker who avoids direct address but can still punch the lights out of someone “spouting / john 3:16 or some other other jesus / christ biblio-code for settler / salvation.”

In the wake of such disgust, grief, and cultural and personal loss, there remains the subtle flicker of creativity: “The story you wanted to write is on fire / paper lathered with bear grease / floating down a river.” Henry’s poems offer guarded hope, though it may come at the price of forgetting.

Let’s forget our diseases

the strings winding us

in decay and desperate

attempts to remember

Or is it the rejoining of flesh to spirit—especially the spirit of love—that urges us to go on with our lives?

I still have this beating

animal to face each morning

asking me for bread and wine

a story to tell against the

loss and lies

As if love would ever

come around again

As if that was where all

this began.

In book’s epilogue, “Chiaaboos at the River Again,” the enduring emissary to the dead has made contact; and like a tender Charon, he ferries souls across the river in a silver canoe. But it seems he will also be joining them, and he wishes to be remembered for the good things he’s done: stoking the fire, passing down old songs, feeding the hungry, warming the children, digging for stories. Gordon Henry’s poetry assures us that the living side of the river will be well tended, and that the lines to tradition, ancestor spirits, and “the beginning we all came from” will remain open.

Published on October 5, 2023