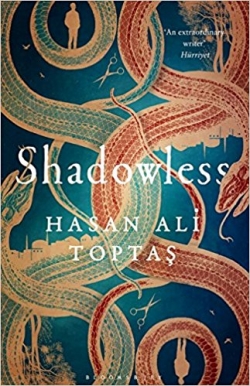

Shadowless

by Hasan Alí Toptaş, translated by Maureen Freely and John Angliss

reviewed by Margot Demopoulos

Hasan Ali Toptaş is hailed as the Kafka of modern Turkish literature, and Shadowless secures that distinction. Given his acclaim in Turkey—he is favorably compared to Orhan Pamuk—the long unavailability of his work in English is remarkable. This novel was first published in Turkey in 1995, and it is only now available in English. Like Pamuk, Toptaş was awarded Turkey’s most prestigious literary prize, the Orhan Kemal Novel Prize. He also received the Culture Ministry Prize, the Çankaya Literature Prize, the Yunus Nadi Novel Prize, the Cevdet Kudret Literature Prize, and the Turkish Writers’ Union Great Novel Prize.

The novel opens in a barbershop in an unnamed Anatolian village. When our narrator enters, “[t]he barber raised his scissors high in the air, as if to toast [his] health,” and he takes a seat to wait his turn. The barber asks him if he’s still writing, and what his new novel is called. What follows foreshadows events in the narrator’s novel-in-progress, the novel within a novel.

“If you mean my novel,” I said, my voice sounding so distant, “I don’t yet know.” The dungeon beads stopped clicking. The barber set down his brush. He gazed out into the street. The blades flashed in his little eyes again, but he was already somewhere else. He was flying through the avenues of the city, to a place far away on the other side of the mountains. Perhaps he’d left something of himself behind in that place: something out there with a barber’s shop just like this one, and a man dressed like a barber who turned his head now and again, to look this way.

The sense of loss, separation, and displacement pervades. Characters appear, disappear and reappear, confounded by where they’ve been, why they left, and who or what took them away. Names are reserved for the disappeared—Nuri the barber and Güvercin the Dove—and for those sent to find them, Mustafa and Ramazin. Other characters and place names are like symbols in a fable: the iman, the muhtar, the watchman, the shoemaker, the city, the government, the mosque. The scenes in the novel grounded in reality, in contrast to lengthy dreamlike sequences, form the novel’s strength. The village, or the city, are simply, and often poetically, rendered:

The sun had set and the streetlights were glowing in the half-light of evening. The hum of traffic filtered in from outside, with the clatter of closing shutters. As one after the other came rolling down, it seemed as if the entire city was closing. And perhaps this was why, as the night encroached, I kept an anxious eye on the world outside the door.

The narrative has jarring shifts in time and place, creating a sense of impermanence that may be emblematic of the powerlessness and invisibility of this godforsaken village. For example, our narrator waits his turn in the barbershop before Nuri’s disappearance, the scenes that follow take place after Nuri goes missing, and then revert back, as if Nuri never left. Surrealistic sequences like these happen throughout Shadowless, such as the following brief excerpt from a pages-long scene: “As he walked on, lights were lights no longer, but bulls spouting fire. No longer bulls, but camels carrying beaded cradles on their backs. No longer camels but sweaty horses, or herds of goats, or flocks of birds, bearing mirrors aloft.” Toptaş’s overuse of these sequences weakens the novel’s narrative.

After his return, Nuri explains to fellow villagers what happened the night he disappeared:

For hours and hours, he’d walked, but without any hope of leaving. He’d imagined himself dying—freezing and burning, sated and starving—as he walked away from the village, as far as his legs could take him. It was almost as if the voices inside him were pushing him there. Unless it was something else, a faraway something else pulling him by the ear.

Nuri’s struggle is certainly Kafkaesque. The novel suggests that some characters may have come from far away and long ago, and a part of them beckons them back. Given Turkey’s history of forced disappearances of entire populations—Armenians, Pontic Greeks, Kurds, Assyrians—the voices calling back these Anatolian villagers may be their own history.

The novel ends with a wink and nod. We suspected all along that the novel is the invention of the narrator, and that is confirmed when he slips himself into the identity of one of his own characters—the man with lather on his face waiting to be shaved in the barber shop from the opening. Who but the author has that power?

Published on April 24, 2018