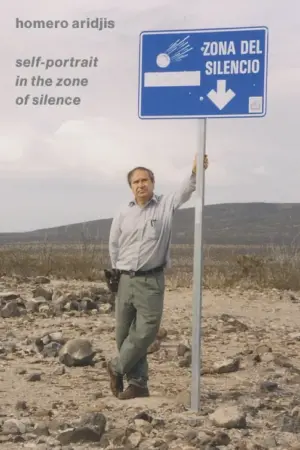

Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence

by Homero Aridjis, translated by George McWhirter

reviewed by Chard deNiord

Now in his eighties, Homero Aridjis, environmentalist, statesman, president emeritus of PEN, and author of over fifty books of poetry and prose, has published a sizeable new book of wildly imaginative poems titled Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence. Blessed with a direct line to his seemingly tireless, oneiric muse, who keeps one eye open on the waking world and one on the dream world, Aridjis’ work casts a beguiling spell on his reader using language, imagery, and subject matter that blurs the line between dreaming and waking. Throughout the book, he takes his reader on poetic flights with a Whitman-like bravado, reveling in both mystical conceits and figurative language, as seen in these credo-like lines from his poem titled “Through The Green Door”:

I am one of eternity’s illegal aliens.

I have crossed time’s borders without proper papers.

Detained by the immigration officers

of life and death, I have jumped

across the chessboard of days.

Aridjis’ claim to be “one of eternity’s illegal aliens” is a clue to the “eternity” he explores in his poetics, where he inhabits a time/space continuum beyond his mere temporal existence while living simultaneously in our exquisite temporal world.

The paradoxical “zone of silence” in which Aridjis writes, tending to worldly matters as an environmentalist and statesman in his native Michoacan, Mexico, at one moment and to his visionary, dream-like poems the next, betrays the rich influence of such poets as Pablo Neruda, Caesar Vallejo, Fredrico Garcia Lorca, Antonio Machado, Rainer Maria Rilke, Tomas Transtromer, and Georg Trakl (the very poets referred to ironically by Robert Bly and James Wright in their ground-breaking journal The Sixties as “the dogs [they] let in”). Unlike these poets, however, Aridjis crosses secular boundaries with a catholic sensibility that’s also Catholic at times, as in his poem “Levitation,” in which he quotes the fifteenth-century saint Teresa de Jesús to emphasize the universality of ecstatic “transcription”: “The difference there is between union and rapture, or elevation, or what they call flight of the spirit, or transport, is that they are all one.” Aridjis aspires to write with a mystical sensibility that’s as metaphysical as it is religious. The transcripts of his ecstasies testify to his unbridled imagination, which divines chthonic, celestial, sensual, and religious themes, often in the same poem with a “first thoughts best thoughts” freedom, as in these two typical stanzas from “Let Us Imagine Lethe”:

Let us think of the gods of death

dressed in voices and memories they say:

“This was here.” “This was there.”

Let us suppose there was no forgetting

and for eternity the eyes go on seeing themselves

in the black mirrors of the instant.

In poem after poem, Aridjis translates his muse’s transcendent dispatches, employing surreal imagery, conceits, and outrageous claims that revel in hyperbole and dream but also reality—what he, in short, calls “poetry.” He divines a transcendent sense, where “the things of this world” serve as figurative tools for his tropes. Like Pablo Neruda, Aridjis views the poet as a verbal wizard who mines memorable language that’s so charged it vivifies even the dust. The last two stanzas of the last poem in the book, titled “Self-portrait at Age Eighty,” serves as a succinct credo for his art and his life:

Paradises there that have no country

and my suns are interior suns,

and love—more so than dream—

is a second life

and I will live it to the last moment

in the tremendous everydayness of the mystery.

Surrounded by light and the warbling of birds,

I live in a state of poetry,

because for me, being and making poetry are the same.

For that I would want, in these final days,

Like Titian, to depict the human body one more time.

Dust I shall be, but dust in love.

In our present age of too much “new” poetry to absorb, Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence serves as a refreshing poetic anodyne, both spiritually and aesthetically, to both lovers of poetry and the casual reader. Although lengthy for a book of poems, at 163 pages, the verse echoes in a paradoxical “zone of silence” that transports Aridjis’ readers to a surreal, absurd, mystical, literal, and paradoxical “zone of silence” in which epiphanies resonate illogically but truthfully in “memorable language.” It is a book that any reader with an interest in crossing over “the alphabet of days” would wish to return to frequently.

Published on December 5, 2023