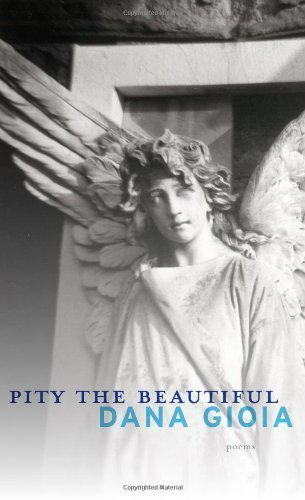

Pity The Beautiful: Poems

by Dana Gioia

reviewed by Kevin T. O'Connor

A provocative essayist and reviewer, an outspoken advocate for the New Formalism during the 1980s and 90s, and the former Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, Dana Gioia is a tested veteran of our very public culture wars. His poetry, by contrast, is often distinguished by its personal, even spiritual intimacy. Its ambition, as well as its sense of limits, is marked by a religious sensibility skeptical of romantic overreaching and trusting in the potential of meter and form to raise clear, ordinary language to another power. Those readers who found subtle music and insight in his previous three collections will find more of the same virtues in his new volume, Pity the Beautiful.

When Gioia’s poems strike rhetorical chords, they tend to be devotional rather than political, as in the opening of the title poem:

Pity the beautiful,

the dolls, and the dishes,

the babes with big daddies

granting their wishes.Pity the pretty boys,

the hunks, and Apollos,

the golden lads whom

success always follows.

While this pithy homiletic litany is slight, it sounds the keynote of a collection that often turns on a vision of deep paradox in the human condition. In longer poems like “The Freeways Considered as Gods” and “Shopping,” Gioia draws on a wider social canvas. In the latter, he appropriates speech acts such as prophecy and invocation to satirize the crass, unconscious divinization of the most prevalent of American pastimes: “Blessed are the acquisitive, / For theirs is the kingdom of commerce.” But while this biblical language is humorous, it hardly works as a Ginsbergian assault on Moloch, and the second half of the poem moves into a more characteristic meditative quest for soul amid the gods of American materialism.

In fact, Gioia’s strongest poems work in lower registers and smaller scales. Likewise, his identifiably Catholic sources are organic, playful, and appropriate to an age of naturalistic skepticism. A self-defining line from “Prophecy”— “The call need not be large. No voice in thunder.”—helps set up the poem’s affecting close:

O Lord of indirection and ellipses,

Ignore our prayers. Deliver us from distraction.

Slow our heartbeat to a cricket call.In the green torpor of the afternoon

bless us with ennui and quietude.

And grant us only what we fear, so thatUnderneath the murmur of the wasp

we hear the dry grass bending in the wind

and the spider’s silent whisper from its web.

Gioia’s imagination is unembarrassed in its use of the iconographic and liturgical—as in “The Angel With the Broken Wing,” which assumes the voice of a santo, a devotional wooden statue carved by a Mexican folk-artist, or “Les Animas” (from the Italian of Mario Luzi), which addresses the souls for whom candles are being lit in preparation for the Day of the Dead.

The poems that rely on end rhyme demonstrate both the risks and rewards of the form. In the book’s opening poem, “The Gift,” the rhymes feel both skillful and natural and elevate the diction and syntax of real speech.

The present that you gave me months ago

Is still unopened by our bed,

Sealed in its rich blue paper and bright bow.

I’ve even left the card unread

And kept the ribbon knotted tight.

Why needlessly unfold and bring to light

the elegant contrivances that hide

the costly secret waiting inside?

The sonnet “The Road” also ends with a rhetorical question and couplet: “The road ahead seemed hazy in the gloom. / Where was it he had meant to go, and with whom?” But here the rhyme sounds more like a fulfilled obligation than a necessary force toward discovery, and the poem pales beside the famous Frost lyric with which it is in dialogue.

The flowing narrative of “The Haunted,” written in approximate blank verse with some deft internal echoing, reveals a poet of more open forms enjoying release from a self-imposed discipline. The plot of this dramatic monologue also shows Gioia’s occasional attraction to the Gothic. In a mansion on the verge of a revel with his beautiful but amoral paramour, the speaker is warned away from a misdirected life by a ghostly, mirroring female revenant:

Her back toward me, she started to undress.

Now I was panicked and embarrassed both.

I spoke much louder. She made no response.

Now wearing an old silk chemise,

she turned toward me, still strangely indistinct,

the fabric undulating, as if alive.

I felt her eyes appraise me, and I sat

half-paralyzed as she approached the bed.

Gioia’s parable offers a twist on the romantic-erotic quest when the speaker reveals himself as a monk: “That’s not why I stay there. / This is the life I didn’t want to waste.” Death may be the mother of an immanent beauty in Gioia’s vision, but the poet also holds out the possibility of transcendence beyond the poetic imagination.

Affirmation lives close to lament, and there is also a strongly elegiac strain in Gioia’s work. The death in infancy of the poet’s first-born son, initially commemorated in “Planting a Sequoia” from Gods of Winter (1991), resonates at the heart of this sensibility. “Special Treatment Ward” touches movingly on this traumatic loss, and the book closes with “Majority,” a wishful farewell to his own tender, speculative images of his deceased son growing up:

Now you are twenty-one.

Finally it makes sense

That you have moved away

Into your own afterlife.

Gioia’s elegy also forms a diptych with “Finding a Box of Family Letters” in which the speaker admonishes himself for dwelling too long in the memories of his deceased father: “It’s silly to get sentimental. / The dead have moved on. So should we.” The poems in Pity the Beautiful present the pathos of their own limits, how aestheticized memory and desire point to mysteries beyond themselves.

Published on November 18, 2013