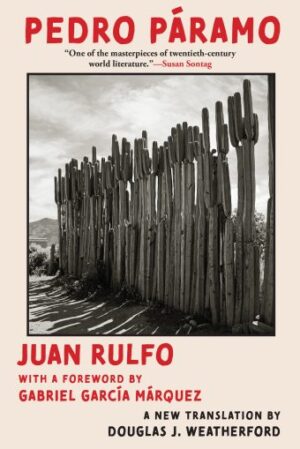

Pedro Páramo

by Juan Rulfo, translated by Douglas J. Weatherford

reviewed by Daniel Rey

It is Pedro Páramo’s blessing and curse to have inspired the Latin American “Boom.” Juan Rulfo’s novella is the key text in modern Mexican literature, but in the English-speaking world it has long been considered an appetizer to the great novels of the Sixties.

This impression—complimentary but also belittling—endures despite a fresh English edition. Writing on the occasion of Douglas J. Weatherford’s new translation, Valeria Luiselli opened her essay in The New York Times by referring not to Rulfo, but to the most famous figure of the “Boom,” Gabriel García Márquez. Weatherford’s new version includes an introduction by García Márquez that, despite supposedly being written “in honor” of Rulfo, is mostly about “Gabo.”

Even when it is not being framed in terms of the “Boom,” critics and publicists keep defining Pedro Páramo through reductive comparisons to other texts. The back cover of the new UK edition quotes a line from the Guardian that describes the novella as “Wuthering Heights located in Mexico and written by Kafka.” Pedro Páramo deserves better. It has sold over a million copies in English and is being adapted by Netflix. It should be read on its own terms.

Pedro Páramo is set in western Mexico between the 1870s and the 1920s, decades that include the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, the Revolution, and the Cristero uprising. Rulfo outlines the premise of the novella in the first three paragraphs. The initial narrator, Juan Preciado, travels to a town called Comala to fulfill a promise to his dying mother—that he claim money owed by his father, the local strongman Pedro Páramo. Guided by a muleteer named Abundio Martínez (an illegitimate son of the title character), Juan Preciado descends into the town as though entering a mythical underworld. As they approach Comala, Abundio reveals that Pedro Páramo died years ago.

Comala—which has been desolated by Pedro Páramo and by political violence—is an eerie, airless place. The first villager (physical or ghostly) that Juan Preciado sees is a woman wrapped in her rebozo who vanishes “as if she’d never existed.” Literally unable to endure the oppressive atmosphere wrought by Pedro Páramo, Juan Preciado dies of asphyxiation. The novella then turns its focus to his father’s rise, heyday, and fall.

Pedro Páramo, whose name means “rock” and “barren plain,” is a harsh, feudal lord. A womanizer and the de facto owner of the fertile land around Comala, he is associated with fecundity—yet his life and afterlife are defined by fatalities. There is the death of his father, killed by mistake at a wedding; the death of his rapist son, thrown off his horse; and the many deaths for which Pedro Páramo is himself responsible. These include Juan Preciado, “just about everyone who attended” the wedding where his father was shot, the concubine who dies in childbirth, the father of his forced bride Susana San Juan, and Susana San Juan herself. As revenge for the lack of mourning shown to Susana San Juan by the villagers, Pedro Páramo starts a famine that reflects the barrenness of his name:

—I’ll cross my arms and Comala will die of hunger.

And that’s what he did.

Comala, especially as it is described by Juan Preciado, is mysterious and paradoxical. The town is “devoid of all sounds” but “full of echoes” and “filled with voices.” Leaves are blown through the streets despite there being no trees, and time is unstable: “The church clock rang out the hours, one after another, one after another, as if time had contracted.”

Comala is an interstitial place. References abound to the underworld and to Purgatory. Villagers say souls are “wandering the earth” or “wandering out and about.” As Juan Preciado describes, “After dropping down out of the hills, we descended even farther. We had left the hot air above and were now sinking into a pure heat that had no air. Everything seemed to be waiting for something.”

The town’s name reflects its depravity (Co-mala) and its fiery climate—the comal is the traditional griddle for warming tortillas. Abundio tells Juan Preciado:

That place sits on the burning embers of the earth, at the very mouth of Hell. They say many of those who die there and go to Hell come back to fetch their blankets.

Pedro Páramo is a nonlinear story written in short scenes that resemble snapshots. It is polyphonic—told by Juan Preciado, at least one third-person narrator, and characters who resemble a chorus. It is a story of archetypes—an everyman, a tyrant, and a son searching for a father. It regularly alludes to Greek tragedy, particularly Sophocles’s Oedipus the King. As in his short story collection The Burning Plain (1953), Rulfo explores themes of land and displacement that evoke the history of Mexico and of colonial and postcolonial Latin America.

Rulfo’s description and dialogue are spare, casting an uncanny atmosphere over Comala and the text. Juan Preciado perceives that “everything was completely quiet, the only sound a moth falling through the air and the whispering of silence.” Rulfo’s voice, particularly in the scenes set in the “underworld,” can be laconic, mythic, and surreal. A sphinxlike villager, Eduviges Dyada, introduces herself to Juan Preciado at the threshold of her door:

—I’m Eduviges Dyada. Come in.

It seemed as if she’d been waiting for me.

That evening she tells Juan Preciado: “I often said: ‘Dolores’s boy should’ve been mine.’ Later I’ll tell you why.”

Women dominate the spirit world of Comala, but during Pedro Páramo’s rule they are routinely abused or put in service of abuse. Pedro Páramo marries Juan Preciado’s mother, Dolores, for her family’s land; Dorotea, a beggar, facilitates the Páramos’ rapes; and the town blames a sibling romance not on the brother, but on his unnamed sister. Susana San Juan, the one character who defies the patriarch, appears to have an incestuous relationship with her father.

Rulfo’s world entertains little scope for women to be more than victims. This is the case even when they disobey men. Dolores sends Eduviges to take her place on her wedding night, but her deception depends on another woman’s compliance. And although Susana San Juan refuses to love her forced spouse Pedro Páramo, she is left “always hidden away in her room, sleeping, and when she wasn’t, acting as if she were.” The women’s lowly status may be part of Rulfo’s indictment of Mexico’s patriarchal feudalism, but it could also suggest an inability to empathize with the story’s female characters.

Rulfo’s tone is generally replicated in Weatherford’s edition and, unlike previous translators, he reproduces the author’s varied ways to indicate dialogue: dashes, single and double quotation marks, guillemets, and italics. This correction not only restores Rulfo’s wishes, but emphasizes a crucial aspect of the novella—its polyphony.

However, faced with the challenge of trying to capture Rulfo’s rural idiom, Weatherford regularly resorts to undue informality: “I had met up with him at Los Encuentros, where several roads came together. I was there waiting, until finally this guy showed up.” Later we read that a sleepy store attendant has been “serving a bunch of drunkards, getting smashed right alongside them.”

Weatherford also impoverishes Rulfo’s famous first sentence—Vine a Comala porque me dijeron que acá vivía mi padre, un tal Pedro Páramo. Weatherford opts for “I came to Comala because I was told my father lived here, a man named Pedro Páramo,” omitting the expression un tal Pedro Páramo (a certain Pedro Páramo). Weatherford’s translation thus loses the original’s dismissive or derogatory connotations—connotations that immediately indicate the title character’s infamy.

Pedro Páramo is a short, demanding work full of paradoxes and layers. Its intensely fragmentary plot provides incalculable interpretative possibilities. Generations of writers have been drawn to it. Thematically, one of the most obvious sons of Pedro Páramo is Carlos Fuentes’s The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962). Fuentes portrays a strongman of the Mexican Revolution who marries to acquire land and is denied the person he loves.

Gabriel García Márquez’s well-documented debt to Pedro Páramo is clear in One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), which shares themes of political violence, a domineering clan, and the allegorical history of an isolated town. The influence of Rulfo is unmistakable in its fabulous first line, which amplifies the phrasing and syntax of this sentence from Pedro Páramo: “Many years later, Father Rentería would recall the night the hardness of his bed kept him awake, eventually forcing him to head outside.” García Márquez also gives two important characters—Prudencio Aguilar and Melquíades—unusual forenames taken from villagers said to have escaped the destruction of Comala. In many ways, One Hundred Years of Solitude is a continuation of Pedro Páramo.

Readers of Pedro Páramo may begin the novella with the “Boom” in mind, but such is the power of Rulfo’s writing that they will find themselves immersed, like Juan Preciado, in Comala’s dense, uncanny world. If Pedro Páramo really is an appetizer to the “Boom,” then it is enough food for a feast.

Published on August 3, 2024