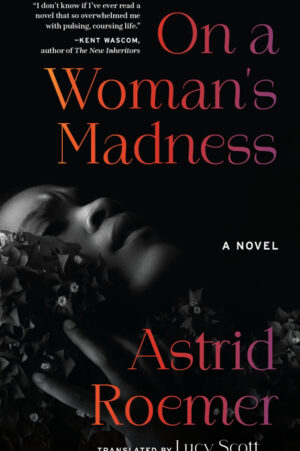

On a Woman’s Madness

by Astrid Roemer, translated by Lucy Scott

reviewed by Liza Wemakor

Matt Richardson describes black queerness as a condition of being both fragmented and fantastic—alienated by norms around gender and sexuality while engaging in rich innovation. In his 2013 book, The Queer Limit of Black Memory: Black Lesbian Literature and Irresolution, Richardson honors the way queer black people “reinvent our bodies, renaming ourselves according to the genders we create, regardless of anatomy” and “remix the possibilities of Black kinship, making family across boundaries not determined by blood.” Though Astrid Roemer isn’t one of the black lesbian authors Richardson examines in his book, her work belongs to this constellation of black queer creativity.

Roemer’s On a Woman’s Madness, originally published in Dutch in 1982 and newly translated into English by Lucy Scott, is difficult, fragmentary, gorgeous, and at times unpredictable, much like its protagonist: a queer black Surinamese woman named Noenka. The novel is saturated with pain, drama, pleasure, and violence, which may rightly invite comparison to classics by Gayl Jones, Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, although Roemer’s writing style is remarkable in its own right.

From the outset, Madness is as floral as a Georgia O’Keefe painting on a literal and figurative level. Noenka takes solace in a greenhouse full of orchids owned by one of her lovers, Ramses, who meets an abrupt, tragic end. Noenka is regularly affected by the flowers’ strong perfumes and their suffocating feminized beauty. Noenka herself is likened to a flower, and she fights an uphill battle against this imposed vision of femininity throughout the novel, not only by escaping the husband (Louis) who oppressed her in their small Surinamese hometown, but by indulging her polyamorous queer sexuality in the capital city of Paramaribo. She becomes progressively more comfortable acting on her attraction to women, and her lesbian confidence peaks when she’s smitten with an older woman named Gabrielle.

Both Noenka and Gabrielle are married to men throughout their romantic relationship, but this seems to be the circumstance of most sapphic women in the world of 1960s Surinam. Patriarchy and Christianity are as pervasive as the flowers that flood Noenka’s eyes and nose; in Paramaribo and surrounding towns, women cannot work or acquire housing without answering to a husband or a (white) clergyman, and the life opportunities that are available to them are constrained by misogyny. The lesbian romances readers witness are carried out in secret, and when they are uncovered, they are met with scorn and punishment (including corrective rape).

The traumatic nature of Noenka’s life informs the structure of Madness. Roemer constructed the novel as a collage of emotionally intense memories that are not always sequential, yet build upon one another. In a recent interview with the Center for the Art of Translation, Roemer affirms that she writes from “an inborn urge to look at everything from multiple perspectives … to compose a fictional biography in a form that would symbolize the ruins of Noenka’s existence,” which defies a neat chronology. By the final act of the novel, we learn that Noenka is involved in a murder that is a consequence of her unwellness and the deep misogyny and antiblackness that have shaped her life. Mirroring the lived experience of mental breakdown, truth in this novel reveals itself unexpectedly and fitfully—solid one moment, a surreal, cerebral landscape the next. Noenka can never quite grasp the love she desires, and that is maddening to her.

In Black Madness :: Mad Blackness, Therí Pickens observes that for black people who are constantly subjected to antiblack violence, madness cannot be reduced to questions of brain chemistry, diagnosis, and clinical treatment. Mental disability cannot be understood apart from race, and black people experience “madness” in ways that reflect their particular circumstances. We are not unchanged by what touches us, and Noenka’s life is touched by so much violence. She aims to live up to her name (said to translate to “never again”) by rebelling against the generations-long colonial and homophobic traditions that haunt her; in doing so, she exposes herself to new kinds of precarity. Refusing to be married to a man and choosing to love a woman labels her as a black madwoman, cast out from polite society into an asylum.

The world Noenka lived in didn’t have room for her kind of love or personhood, and she suffered for it. Yet somehow, by the end of the novel, Roemer’s heroine hasn’t abandoned the love she’s suffered for. This seems miraculous, and it is but one reason to be thankful for this long-overdue translation of one of her most important works.

Published on May 23, 2023