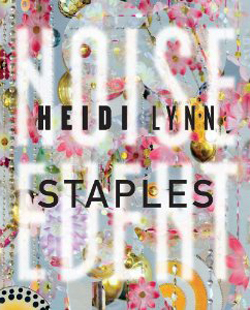

Noise Event

by Heidi Lynn Staples

reviewed by Elizabeth T. Gray Jr.

Heidi Lynn Staples’s third book is centered in loss, language, and her return, after some years away, to the landscape of her native Florida. The poems are built using compositional techniques found in her earlier Guess Can Gallop (New Issues, 2004) and Dog Girl (Ahsahta, 2007), including collage, while her source texts range from seventeenth-century ethnographic accounts of Florida’s indigenous peoples, Audubon’s and Fodor’s guides to Florida, and the author’s own juvenilia. The result is a lithe and complex book that is both linguistically inventive and emotionally compelling.

In the first of the book’s four sections, Staples combines fragments from Fodor’s Guide to Florida with recollections of an intense adolescent love affair and of standing by through the death of her grandmother. The poems teeter on the edge of sentimentality without ever losing their balance:

it’s true, he was a boy with a go-cart who drove by

faster than elevated coastal ridges and

dry, sandy soil conditions. I blushedpinelands and pine

scrub. the words between us nonnative fish.[. . .]

I didn’t yet know that in her

body formed the future and the future requires fire

for the release of its seeds,that she was leaving that the future is patented and listed as real-estate

like lake flooding during hurricanes in the late 1920s

the blood leaving her face; disrupting the flow of water into

the Everglades.

Rarely have I encountered an elegy that required such engagement of a reader or produced such an intense, shared sense of many-layered loss.

“Florida Native,” the less-successful poem that makes up the book’s second section, uses a substitution procedure and includes material from Staples’s high school yearbook, the diaries of Jamestown Colonist George Percy, and a seventeenth-century manual written by a Spanish missionary whose objective was to convert Florida’s native population. The seventeen poems in the third section, “Palm of Palms,” are both acrostics of Florida fauna and flora and homophonic translations of selected prayers and psalms. Here “Psalm 23” speaks of Florida’s red maple:

Reborn as bright shaker; sigh shroud gnat ant.

Emigrated stream

Dew bright dawn windMetaphors: me read of stream resided the stellar

Are tours.

Please ray stars of bright

Lull: me read of stream wind the laughs of bright lush yes

Err is flame’s wake.

While, in places, the poems seem to lose their connections to psalm, prayer, or semantic sense, the music is astonishing and the reader’s involvement intense—which is the point.

According to Staples’s endnote, the fifteen poems in the final section, “Barking at Blue Clouds” (a title lifted from Lyn Hejinian), were written using various techniques, “including a chance-based procedure incorporating texts cut up and pulled out of a paper bag, collage, and homophonic transliteration.” These complex poems include repetitions, bird calls, and lines that recur across the series while gradually changing sound and shape with each new appearance: “(Thesis valediction and ambivert.)” becomes “(Theist vandalism grants ambient yurt.)” becomes “(Thesaurus ventriloquism ground is am be land you’re.).” This is sometimes opaque but musical and agile language, strongly centered in Staples’s love and despair for the psychic and physical landscape of her past and native Florida.

Published on February 23, 2014