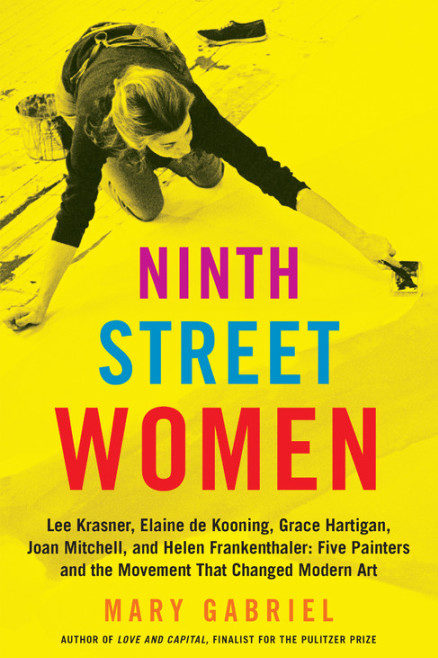

Ninth Street Women

by Mary Gabriel

reviewed by Lisa Mullenneaux

It’s hard to believe that Abstract Expressionism, the movement that shifted the center of the art world from Paris to New York City, was once shunned, and Jackson Pollock mocked as “Jack the Dripper.” We have grown up with its images as cultural icons and with the legends of the “outlaw” painters who created them. Mary Gabriel, whose Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2012, sets out to tell the story of five women—Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler—whose work was essential to the movement, but whose importance, until recently, has been ignored.

Gabriel’s point (and it’s true for all revolutionary movements) is that these painters were so far outside the art milieu of the ’30s and ’40s that they were “visible only to each other.” She begins her 900-page tribute to the painters’ belief in their talents by recreating a desperate act. Shut out by the uptown galleries, in May 1951 these renegade artists transformed a derelict store on Ninth Street in Greenwich Village into exhibition space. For a few months, art world movers and shakers came to sniff out the seventy-two exhibitors, who knew they had a hit. Thomas Hess, longtime ArtNews editor, would call the five women in their midst “sparkling Amazons.”

Gabriel’s research methods reflect her belief that art should be seen as integral to the time and place where it was created. Each painter’s biography is woven into a dense cultural history of the years 1929–1959 in America, which witnessed the growth of consumerism, a world war, and changing roles for women and the family. She places Krasner and Elaine De Kooning at the beginnings of the movement (1928–1948) and Hartigan, Mitchell, and Frankenthaler as a kind of second wave (after 1948). The entire project, decades in the making, required sifting through 200 interviews spanning sixty years, and many letters, journals, and notes in collections, both public and private. The result is intimate and compelling; you feel the solidarity of dead-broke artists, the oblivion of nights at the Cedar Bar, the thrill of a successful opening.

Lee Krasner (born Lena Krassner in 1908) would, like her colleagues, reinvent herself without any support from her Russian immigrant parents. Her relationship with a drunken, abusive Russian ex-pat painter, Igor Pantuhoff, foreshadowed her marriage to Pollock. When Elaine Fried of Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, moved in with Willem (Bill) de Kooning in 1938, he was 34 and she just 20. They would be an art-world power couple for the next twenty years, but Elaine’s career, like Krasner’s, was overshadowed by her husband’s fame.

Grace Hartigan didn’t pick up a sketch pad until she was 19, but five years later, in 1948, she had given up a job, a husband, a lover, and a young son to devote herself to art. Only she believed she could make it work. Gabriel describes how the artist stood outside MOMA and vowed that one of her paintings would hang there one day. In 1953, the museum purchased The Persian Jacket, only the second painting Hartigan had ever sold.

Helen Frankenthaler’s elite upbringing couldn’t have been more different from Hartigan’s. She started painting with Rufino Tamayo, continued at Bennington with Paul Feeley, and for the next sixty years she rarely stopped. Frankenthaler assisted the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Color Field painting with her invention of the soak-stain technique.

Like Helen, Joan Mitchell grew up in an atmosphere of wealth and privilege, but in Chicago, not New York. Once she took up painting, Mitchell found her passion as well as her profession. Her marriage to Barney Rosset was a bridge to her future. In Gabriel’s words, “in that future, they would make history,” with Rosset in the world of publishing and Mitchell as one of the greatest artists the US has ever produced.

Gender bias in the art world isn’t news, but here it is spiced with the explosive candor of Krasner or Mitchell. “Any woman artist who says there is no discrimination against women in the art world,” said Krasner, “should have her face slapped.” She would know: she was 43 before she had her first solo show and 75 before her first retrospective in 1983. “Really,” Krasner told a reporter at the time, “it shouldn’t be a once-in-a-lifetime thing.” Gabriel reminds us that biographies of all the painters (except Frankenthaler) have appeared only recently, resentment from male artists being endemic to the field.

As she did for Jenny Marx in Love and Capital, Gabriel shows that these five painters were not merely muses or helpmates, but deserving of recognition for their own contributions to modern art. That recognition didn’t come easily. Clement Greenberg, for example, whose pen could make or break an artist’s career, denied his former lover Frankenthaler credit for inventing Color Field painting until the early ’60s, crediting Ken Noland and Morris Louis instead. Being “Clem’s girl,” one suspects, may have been an asset to Frankenthaler’s career when she was unknown, but not when she was knocking at “the club.” “The fifties was a ‘boys club,’” boasted one of Joan Mitchell’s male friends, “but some of the women painted almost as well as the boys so we patted them on the ass twice and said keep going.” The point is that they did.

Published on July 2, 2019