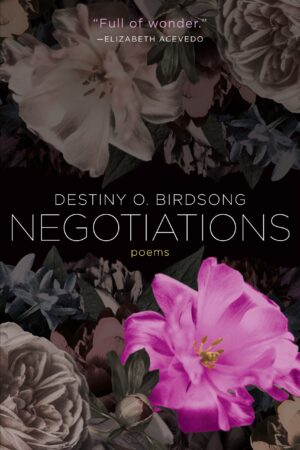

Negotiations

by Destiny O. Birdsong

reviewed by Lesley Wheeler

Into the trolling and rancor that poison conversations about “American” identity enters the compelling testimony of Destiny O. Birdsong’s debut poetry collection. This beautiful and devastating book prioritizes complexity; here, identity is a process emerging from relationships, more interesting in mediation than definition. For example, “The 400-Meter Heat” begins:

I’m most American when I reach for more ketchup

as Shaunae Miller dives across the finish.I’m blackest when Allyson Felix collapses on the track,

knees up, concealing her last nameand the letters USA blistering her chest.

I’m saddest whenever two black women are competingbecause I never know who to root for,

and I’m arrogant enough to believe my split loyaltyfails them (which makes me more American again).

This is how it feels to be a problem:

The experience of watching a race is conditioned by race and gender, but Birdsong goes on to undermine the event’s premise, valuing “transubstantiation” more than “victory, which is neither sympathy / nor love, nor more sacred than the foot-fall.” There can be no easy resolution to a “problem” with so many variables, but a thoughtful person wouldn’t want one.

Negotiations explores anger and vengefulness in light of brutal histories; the self-divisions accompanying pain and illness; and recovery of desire and self-love after rape. These are some of the most difficult topics a poet can tackle, so it’s all the more remarkable that Birdsong’s work adds up to joyous survival and a commitment to taking up space. The emotional power of this book springs from its unrelenting insistence on admitting every nuance, every complicity. At least as impressive is the craft that channels the power. In over a hundred pages of poetry, with many pieces several pages long, not a word feels less than necessary.

A precondition of successful negotiation is understanding your adversary. Birdsong offers many portraits of Americans rejecting or undermining Black women’s personhood, and she brings them into focus through an array of strategies. In “Emeritus,” she damns a perniciously ignorant professor by ending the poem with his own words of workshop critique: “At this point, / only the Vaseline is interesting. An ethnic thing, yes? / Perhaps, then, a poem from the perspective of the jar?” The tone is cool, observational, but other pieces convey heat. “Elegy for the Man on Highway 52,” an extended curse, flings back a racist man’s prejudices with lines including “I hope someone tells you everything your culture made / is meaningless: Stonehenge, democracies, and you.” In “Fable,” Birdsong enters the imagination of a boy who terrorizes girls while dressed in a bear suit; the layers of masking in this disturbing poem have a dizzying effect. Predation in “Fable” foreshadows an intense sequence of first-person treatments of sexual assault and its consequences. Three blazing poems begin by naming the adversary “My rapist” and interrogating how a violent man gained power over her, but the last ends in “a ritual of refusal” and holding the rapist to account—literally, as he’s pursued by collection agents.

Other arbitrations occur within the poet as she considers injuries and how she might heal from them. In “ode to my body,” referencing Lucille Clifton’s “the lost baby poem,” Birdsong plays two roles: the griever and her own lost baby. This poem addresses what the book’s “Notes” call “an independently animate self” as she acknowledges the “so many ways / i have tried to discard you.” Subsequent poems consider how disease can alienate a person from herself as well as stage reconciliations among the estranged parties, especially in the haunted ghazal “Auto-Immune.” Flesh, spirit, and mind are entangled but divided, too, in poems about mental health. In “failed avoidance of ‘the body’ in a poem,” anxiety takes up residence in “the bones / behind your face.” The speaker wonders if she can forge a new relation to her skeleton, playing those occupied bones like a flute. Exploring sexuality, “Long Division” reveals how sexual desires factor inside a person: “Twenty percent of me wants women,” “Sixty-nine percent of me wants men,” “The rest of me just wants a bed alone,” “half is terrified of men,” “The other half remembers always—and sometimes / with tenderness—my rapist.” As difficult as this struggle is, however, Birdsong concludes “Long Division” by calling “let them come,” an invitation to sexual ecstasy. The second half of the book celebrates appetite and describes the process of a woman learning to satisfy herself.

Birdsong’s poems are the negotiations, charged with declarative force in and beyond their curses and blessings. In “Pact,” for instance, she promises a friend to value her life even if others fail to, using poetry to publish the deal. The art form as Birdsong uses it is contractual and precise; somehow she binds wild complexity into spare language. Negotiations goes for broke in a way that makes all of us richer.

Published on January 19, 2021