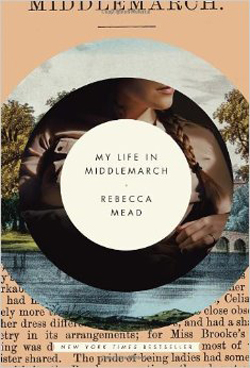

My Life in Middlemarch

by Rebecca Mead

reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

If you’re reading this, chances are you think of yourself as a book person. You might have even read George Eliot’s Middlemarch, the subject of Rebecca Mead’s hybrid work of literary criticism and memoir. But even if you haven’t, Mead and her account of her lifelong journey through Middlemarch will immediately strike a chord as something universally felt by book people. Mead is both learned and astute; on the page she comes off as an inquiring mind, on par with Eliot and her beloved heroine, Dorothea Brooke: sensitive, cunning, and winningly relatable.

Mead first read Middlemarch as a teenager living in a rural southwestern English town. She was seventeen, two years younger than Eliot’s Miss Brooke, and yearning to escape her insular world and attend Oxford University. The plucky heroine’s story of downfall and triumph etched themselves upon her heart, and, as her investment in the novel grew, she increasingly identified with the young woman who, like herself, “wanted . . . to do something.”

Mead provides several instances of overlaps between Middlemarch, her life, and that of its author. Often called a “home epic,” the novel charts the making and breaking of families, the ways that the ambitions of youth take one away from home, the widening gap between old and new money, and its effect on a small town during a period of change in English history. Mead thus finds parallels to her life on the home front: she marries an older man, inheriting grown stepsons; she departs for New York for a career in journalism. When she revisits the novel in her forties as a wife and mother, she’s soothed by Eliot’s compassion toward her characters. She is a stalwart champion for the Dorotheas and the Lydgates, who make mistakes and live with them gracefully. “Eliot,” writes Mead, “is the great artist of disappointment. Her characters, even the good ones, stumble, fall, and fail—not into inexorable tragedy, for the most part, but into limited, mortal resignation.”

Mead’s own anecdotes, although necessary for her genre-bending narrative to work, are not wholly enlightening in and of themselves. Plenty of people go through the life changes that she does without claiming a causal link to literature. Her stories often feel tacked on, unnecessary, and didactic in a way that even the morally righteous Eliot would not be guilty of. Perhaps this is because she maintains a subtle but important remove from the novel: her interest in Eliot is essentially journalistic, inspired by Eliot’s own use of her life as inspiration for her fiction.

Mead’s thorough and engaging scholarly treatment of Middlemarch lights the way for us. Her interpretation of Eliot’s theme of empathy is most compelling, relying on textual and biographical evidence derived from Eliot’s letters and journals. Mead explains Eliot’s agility in shifting between characters, how she “examines Dorothea’s emotions under her microscope, as if she were dissecting her heroine’s brain, the better to understand the course of its electrical flickers” in one paragraph and turns to her husband’s flickers in the next. Part of what Mead appreciates about the book is how, under its influence, her ability to empathize with characters other than Dorothea has evolved. In reading Middlemarch, “We are called to express our generosity and sympathy in ways we might not have chosen for ourselves. Heeding that call, we might become better. Setting aside our own cares, we might find ourselves on the path that can lead us out of resignation.” The takeaway from both books, then, is an essential lesson in humanity.

My Life in Middlemarch achieves what good criticism strives to accomplish: it compels the reader to seek out the original text and experience it for herself. Though I’ve read Middlemarch more than once, I closed Mead’s book eager to take my worn, Post-It-fringed copy of Eliot off the shelf. But Mead’s example also invites us to apply her method to all the stories and characters that we like. I think it’s no coincidence that since finishing My Life I’ve coveted the Penguin Drop Caps edition of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man—the book I consider to have shaped my literary life. Mead reminds us why one is a book person in the first place.

Published on July 1, 2014