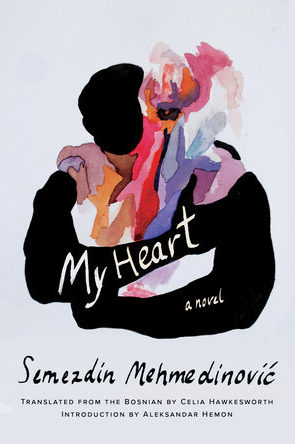

My Heart

by Semezdin Mehmedinović, translated by Celia Hawkesworth

reviewed by Hua Xi

It is a difficult task to translate the heart to paper. But Semezdin Mehmedinović’s autobiographical novel, My Heart, now translated by Celia Hawkesworth, manages to imprint something like the heart onto the page, something beating, aching, pulsing.

Mehmedinović’s book of three essays is a series of variations on heartache. My Heart opens with the story of the author’s own heart attack and closes with the story of a heart attack experienced by his wife. In the middle is an essay about his son. These are major incidents, watershed moments of love and loss in a family. But Mehmedinović’s’s book is as much about quotidian details as it is about these life-and-death events. The book is equally about the way the sky looked in places he once lived, a particular flower on the side of a road, the odd shapes of the hills in a film he’s watched, or a blue dress worn by a passerby.

The novel’s prose travels back and forth across decades and landscapes. Things in the present are reminders of things in the past. Things in the past connect together into faint patterns but also rapidly dissipate and are never mentioned again. The author and his son Harun are driving through present-day America when they stop briefly to look at the stars. Almost immediately, the author begins recalling a specific crowd of winter stars in the bare sky above Sarajevo in 1993, jumping back dozens of years. Throughout the book, Mehmedinović’s prose is full of detours like this into tiny details of memory.

By Mehmedinović’s logic, nothing is ever over. Not the desert he drives through with his son, which goes on and on, continuing off the edge of the page. Not particular colors, like the color red, which is the color of his son’s bandana in the second essay, “Red Bandana,” which is just like the color of a scarf worn by his grandmother, which is like the color of the sand they travel through. Not the snow, which begins falling over outside his window in DC at the beginning of the story and goes on falling over his travels with his son and at the airport where they part, and which continues falling into “Snowflake,” the story about his wife’s loss of memory. The act of noticing is not completed simply because the past is over. “I feel the same sorrow half a century later, remembering it now,” Mehmedinović writes when thinking back to a childhood memory.

Many autobiographical novels try to tell you something about life. Mehmedinović’s prose feels more like life itself on the page. It is filled with the busy, daily matter of living, which Mehmedinović recounts in vivid, color-filled prose.

It is fitting that the book is also fascinated with other forms of documentation. Mehmedinović frequently refers to paintings; Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Dalí all make appearances. He repeatedly quotes poets, and many scenes are compared to stills from films. The author’s own son is also a filmmaker and photographer who carries a camera for much of the book. Most of all, Mehmedinović repeatedly brings up and describes family photos, some printed, some taken on a cell phone, some in an express photo booth. These family photos tie the book together, a novel which feels like it is being told by someone standing in the present, looking at a photo from the past.

One particularly elegant line stands out. Hidden in a paragraph about something else entirely, Mehmedinović writes, “late snow must have fallen somewhere nearby.” Nothing else is said about the snow just then. But you get a great sense of peripheral vision with this single detail. Things are happening everywhere all at once, even at the edges of the story. They go on happening whether or not we stop to notice them. The heart is very full.

Published on August 17, 2021