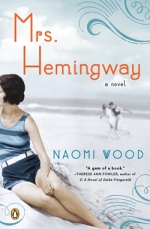

Mrs. Hemingway

by Naomi Wood

reviewed by Laura Albritton

It’s been fifty-three years since Ernest Hemingway died, but society can’t seem to stop picking over his corpse. Recent volumes such as Hemingway’s Boat by Paul Hendrickson and the novel The Paris Wife by Paula McLain plunge once again into his notorious past. In the case of Hendrickson, the biography had a refreshing angle, even if much of the criticism of the writer’s personal shortcomings felt familiar, while The Paris Wife assumed the voice of first wife Hadley Richardson in an imagined memoir.

The latest foray into Hemingway excavation is Mrs. Hemingway, a novel by British author Naomi Wood. In this, her second fictional work, Wood projects herself into the psychological realities of the four Hemingway wives, Hadley, Pauline Pfeiffer (“Fife”), Martha Gellhorn, and Mary Welsh. Wood is a more than able writer and eschews the temptation to mimic the great man’s language (unlike The Paris Wife, which at points echoes A Moveable Feast).

Wood opens the story in 1926 in Antibes as things are coming to a head: “Everything, now, is done à trois.” This is Hadley, of course, referring to the way in which wealthy, bohemian socialite Fife infiltrates the Hemingway ménage. We flash back to 1925 Paris, when this “expensive-looking girl” first enters their lives: “It had been fun at first: the three of them sitting up late every night, talking about books and food and the authors whom they liked for their personalities but not for their prose.” Hadley confides that: “In Paris, his beauty has become notorious; it is shocking what he can get away with. . . . What contrary feelings he stirs in men. With women it’s easier—they snap their heads to watch him go and they don’t stop looking until he’s gone.”

In Hadley’s section, Hemingway exists primarily as husband, lover, charmer, and betrayer; writing is just part of his seductive appeal. In his second wife’s section, writing becomes more prominent, although still linked to sexual appetites. This Mrs. Hemingway, Pauline Pfeiffer, hopes to keep her husband productively engaged in his study: “Writing, Fife knew, would keep her husband going straight.” It’s 1938 in Key West, well into their married life, when Ernest encounters the beguiling young writer Martha Gellhorn in Sloppy Joe’s bar and brings her home for dinner. His second wife recognizes the uncomfortable poetic justice of the situation: “Oh, yes: Fife knew there was a special place in hell for women who did this to other women.” Life becomes à trois once again, with Martha hanging around until she catches Fife weeping.

The novel focuses so obsessively on the dissolution of each relationship that an equally accurate title might have been Infidelity. In war reporter Martha Gellhorn’s section, it’s 1944 in Paris; her husband has just liberated the swanky Ritz Hotel from German officers. In another, more modest establishment she muses, “Today he would surely be longing for the sawmill apartment and his lost Saint Hadley: a woman all the more exquisite for her generous retirement of the title Mrs. Hemingway. A title Martha has come to hate.” Her admiration for the great man has degenerated to contempt: “Everywhere she goes she finds herself in the shadow of Ernest’s propaganda. It is exhausting: her husband’s need to self-aggrandize.” When she discovers he’s written a love poem to another reporter (Mary Welsh), Martha’s disappointment is mixed with relief.

The book culminates in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961, as Hemingway’s fourth wife, Mary, sorts through the dead man’s papers. She tells everyone that Ernest accidentally shot himself, although others doubt this. In the events leading to and after his suicide and in flashbacks to Cuba, Wood grows more generous with Hemingway the writer and Ernest the man.

Mary recalls life at the Finca, Hemingway’s Cuban home: “What a life of plenty this was! And when he published The Old Man and the Sea, after a long time when no one much had liked his stuff, the world once again went mad for Ernest Hemingway. Accolades, sales, and a Nobel Prize; nothing, it seemed, could be improved upon.” Yet as the widow remembers his increasing depression, she cannot keep up the fiction of an accident any longer: “But maybe Ernest had had more than every man’s sackful of darkness. No man should be asked to live with so much sadness . . . Ernest chose to go, she finally thinks.”

Only when he’s brought low by mental illness does this fictional character finally become sympathetic. But, for all that, Mrs. Hemingway is addictively readable, an exposé of adultery and ego. It appears the Hemingway industry, fixated on his mythic personality, machismo, and love life, will not be going silent anytime soon. Each new book pays tribute to his literary achievements, but these are often subsumed by biographical detail, which grows more lurid with each retelling. It’s as if we have some persistent need to punish his ghost for the writer’s out-sized talent.

Published on June 24, 2014