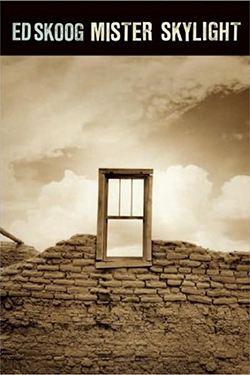

Mister Skylight

by Ed Skoog

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Ed Skoog’s debut collection offers poems that are crazy and compelling in the way they drive, or are driven by language way beyond the realm of everyday idiom.

Sneakers carry tons of teenaged sissies

past acceptance, running laps around our

less imagined selves. We spring from asphalt,

masculine adults with reasonably

priced conveyances, these normal dudes now.

Fresh and imaginative in the moment, Skoog’s style arises from a twentieth-century movement that took flight with Wallace Stevens and culminated with New York School poets Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and David Shapiro. Skoog’s work displays the same enigmatic poetics and verbal montages, a similarly disjunctive syntax, and seemingly unrelated juxtaposition of image and phrase. And, as with Ashbery and Shapiro, readers must surrender their demands for whole meaning in the narrative sense to enjoy the verbal play—the sounds, phrases, and crazy connections that suggest new ways of reading the world.

In these stanzas from “Mister Skylight,” one hears echoes of Stevens, sees the splash of modern painting, feels the mind wandering from the day’s labor.

Ah, send the essential workers back to bed

and suffering that brings them

to keep working on the renovations,

painting of a marsh, whose every wandering

off the canvas into the music

comes from the paint-plastered radio

whose plug droops into the dropcloth.

There’s also sense of human fallibility in these verbal tumbles, which are really not tumbles at all but careful reconstitutions of wind-fallen fruit from the brain’s wide orchard.

In Section II, Skoog offers some beautiful, stylistically calmer poems like “Home at Thirty,” “The Carolers,” and the more ethereal “Early Kansas Impressionists.”

Silly now, when she visits

dreams, or I visit her, my mother,

in new condos at belief’s edge

where the neon restaurant’s lawn

shallows with winter.

These pieces are more typical of well-behaved American poetry. But the riskier, original, yet still coherent poems in Section III—“Like Night Catching Jackrabbits in Its Barbed Wire,” “Pier Life,” “Recent Changes at Canter’s Deli,” and “Inland Empire”—are some of the volume’s best. In “Like Night Catching Jackrabbits in Its Barbed Wire” (where neither jackrabbits nor barbed wire are mentioned), a young man celebrates his birthday by going out drinking and bowling with friends. During the night he runs into a drunk Marine just back from Iraq who steals his beer. The soldier’s buddy apologizes, and a chaperoning officer says, “Don’t worry.”

But I’ve been beaten up by soldiers before.

I know how certain and nearly good

fists feel when the flesh is hungry for touch.

It’s a sharp insight, and the revelations continue as the partiers drive to Joshua Tree and a motel

where Gram Parsons

died twice, in 1973. The first time, his hooker

expertly shoved a cube from the ice bucket

up his ass, restored him, and yet

he knew enough of life to shoot up again.

Leaving the ashy print of Frost’s “Fire and Ice,” Skoog takes us deeper and deeper, as the waitress asks the birthday boy, “Are you a Marine?” He says he feels

underwater, undersea

five thousand feet above its level

in the entangled, ragged arms

of the Joshua tree, which is a lily,

and when I wake from drowning,

beyond the Pioneertown Motel window,

the mountains are still deciding what to wear.

My wife pours orange juice into a green glass

beside black crumbs of birthday cake.

The tension of being under and above, away and home, clear and confused charge Skoog’s linguistic figures. He is constantly “buried, unburied,” “speaking to no one, not being spoken to,” “waking, or refusing to wake.” In the long title poem, “Mister Skylight,” drawn, in part, from the experience of hurricane Katrina, a hog “eats whole bouquets, eats bouquets whole,” while the river “Eats whole towns. Eats towns whole.” On the whole, this works well as a lyric interrogation of value and meaning by a deeply engaged, enlightened, and yet confused speaker, but it can also feel careless as in this otherwise beautiful section of “Mister Skylight.”

Stumbling toward the kitchen

I switch the darkness off,

disturbing a triangle moth who,

thinking perhaps that night

has moved into my black T-shirt

flutters toward me and clings

with undovelike feet.

The word “undovelike” disregards the small, exquisite gift of that moth’s clinging and distracts from the lovely image.

Skoog gets close and pushes away like this constantly in the 322-line title poem “Mister Skylight.” We learn from the book jacket that “Mister Skylight” is an emergency signal to alert a ship’s crew but not its passengers of some disaster. In an online interview, Skoog told Dave Jarecki that he struggled about whether or not to put a note in the title. “I thought the work really takes place in the imagination,” he said. “I’d rather let things be in the language that they are, rather than having any reference to the world.” It’s an important question in art, but in this case knowledge of the term deepens its haunting power.

Skoog’s rejection of language’s referentiality achieves some balance with his obvious skills as a writer, making many of his lines and stanzas surprising and beautiful. But there’s no true trajectory in a poem like “Mister Skylight.” The larger meanings are repeatedly deferred and Skoog actively destabilizes the conventions of telling and of the way speakers and readers relate to one another.

I am one long hear. Put your hand in my mouth,

let me taste, and in return, feel all my orbits.

To borrow an expression from a recent essay by Carmine Starnino, there’s no “lazy bastardism” in Skoog’s work, no desire to “heed the wishes of the common reader out of populist duty.” Despite Skoog’s interest in people from all walks of life, he is really writing to other poets. And while I enjoyed the trip, I’m still not sure where I’ve been. Maybe Skoog is in a constant state of looking for an understanding reader with whom he can rest his words. As he writes in the final, beautifully lyrical poem, “Postscript: Autobiographical”:

I rode across the Argentine, my spokes

speaking for me, to the house of a friend.

Published on June 20, 2013