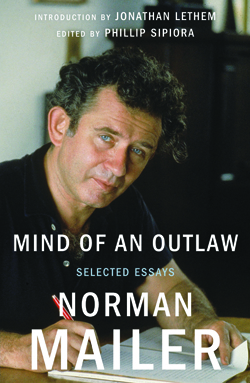

Mind of an Outlaw: Selected Essays

by Norman Mailer

reviewed by Okla Elliott

Whatever one’s assessment of Norman Mailer’s prodigious output—and the opinions on this matter are as contentious as they are varied—it can be safely said that few writers’ careers match the historical span of Mailer’s. His first novel, The Naked and the Dead, was published in 1948 and his last title appeared in 2007, with over thirty books and myriad shorter pieces in the intervening years. He therefore produced work in seven different decades. But what lends Mailer’s career its historical sweep is not merely its longevity; his subject matter was American culture and history, and he anointed himself the chief chronicler of his nation, which he loved and criticized in equal measure.

Phillip Sipiora has usefully organized Mind of an Outlaw by decade, starting with the 1940s, which are represented by a lone essay on Mailer’s choice to support the Progressive Party over the Communist Party. The following decades are more fully represented, with perhaps the 1950s and 1960s being the most interesting, since those were Mailer’s most prolific years in terms of the essay form. This was also when he was helping to invent New Journalism and what we today call creative nonfiction.

From those two decades we get Mailer’s two best-known essays, “The White Negro” and “Superman Comes to the Supermarket.” But the collection also includes his excellent piece “Clinton and Dole: the War of the Oxymoron” about the 1996 presidential election, as well as his assessment of recent writers like Bret Easton Ellis and Jonathan Franzen—both of whom he finds admirable and lacking in various ways. As Jonathan Lethem writes in his introduction, Mailer was a writer “moving through American history as a kind of disastrous recording angel.” After reading these essays in chronological order, that seems like an accurate assessment.

But what makes Mailer such a first-rate essayist? William H. Gass defines an essay by telling us what it is not.

An article is not an essay. Articles lie about the lay of their land. An article pretends to be clear about its objective and then must pretend to reach it . . . Moreover, the article does not halt at any point along the way to confess that its author is lost, or that its exposition has grown confused, or that there are attractive alternatives here and there, that its conclusions are uncertain or unimportant, that the author has lost interest; rather, the article insists on its proofs; it will hammer home even a bent nail.

The word essay comes from the French verb essayer (to try, to attempt). Mailer follows Gass’s dicta about what an essay must do; he tries to enter into the mystery of his subject matter—admitting his limitations, prejudices, and predilections along the way—and he attempts to bring the reader along with him on his exploration. In Mind of an Outlaw, we see a capacious and unusual intelligence in deadly serious meditation on everything from counterculture to literature to masturbation to philosophy to race relations—and all this in a prose that never resorts to ossified thought but insists on dynamic thinking.

Mind of an Outlaw is at once a master class in the essay form, a detailed look at the cultural and political life of seven decades in American history, and a fascinating chronicle of the development of a great and controversial writer. In “First Advertisement for Myself,” Mailer writes: “I am imprisoned with a perception which will settle for nothing less than making a revolution in the consciousness of our time.” In “Raison d’Être,” his first piece for the Village Voice, he writes: “the only way I see myself becoming one of the cherished traditions of the Village is to be actively disliked each week.”

That ego, which could pendulum from grandest self-glorification to the most abject desire to be hated, is fully on display in Mind of an Outlaw, as are a dozen stations in between. The book’s reception will undoubtedly be like that for most of Mailer’s books: derision and praise, dismissal and flash-canonization, and, since it is nonfiction, favorable comparison with his fiction. I wish I could offer something that falls outside the usual reactions, but I have to say that while his novels are far better than some critics give them credit for, Mind of an Outlaw gives the final proof that Mailer’s greatest contributions to American letters are his innovative and virtuosic forays into literary nonfiction.

Published on May 22, 2014