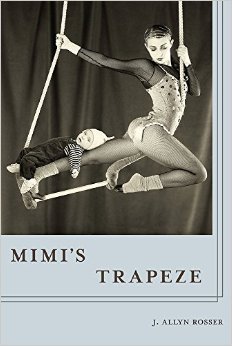

Mimi’s Trapeze

by J. Allyn Rosser

reviewed by Chard deNiord

J. Allyn Rosser’s new book of poetry, Mimi’s Trapeze, leaps from one stunning poem to the next. Writing with all the wit, polemical acumen, metaphorical daring, and formal skill of an eighteenth-century master, Rosser’s sensibility is a most welcome response to the patriarchal arguments of the past. These poems open vistas onto Rosser’s subversiveness, as in these lines that recall Dickinson:

A rabid raccoon, aprowl

In blood-thrall thrill,

Possessed more wholly

Than stake-burnt witches,

Has a vicious mission,

Wants to bite.

(“Jill’s Apology”)

In the title poem, Rosser unravels a narrative reminiscent of Robert Frost’s “The Witch of Coos,” inviting her reader into the speaker’s attic to tell the shocking story of her great-grandmother’s decision to abandon her son and run away with the circus. The voice in this poem demands a colloquial verse that Rosser is more than up to:

That’s the trapeze bar.

I should hang it from the ceiling, right?

That would make more sense. I keep it on the desk

so I can sit here and grip it. Helps me think.

It belonged to my great-grandmother Mimi,

Who ran off with the circus. It’s true!

Funny how they say trapeze artist.

Not performer or acrobat or gymnast.

Like escape artist. Is that really an art?

One might say that Rosser herself has run off with the circus in this book, escaping by “sheer impulse, / nothing you could practice.”

A master of both free and formal verse, Rosser moves forward gracefully in Mimi’s Trapeze, making traditional forms new, her free verse topical and trenchant without being talky. The combination of sophistication and contrariness informs her poetry, such that two equally vital voices—one formal, the other informal—summon different kinds of “poetry.” This is manifest throughout the book, alternating between such exquisite formal lines as these:

The sensation was a first and last: sweet

to feel the vigilance at last suspending,

the chronic stress of constantly pretending

to know—have known!—what all the others knew.

(“Gym Dance With The Doors Wide Open”)

and such tight free verse as this:

Those words that measure the distance between

what you thought you’d think,

what you wanted not to have,

what you felt you’d feel,

and what you do.

(“Self Pith”)

Rosser entertains with a vast array of subjects, from a widow’s recipe for soup, happiness, loss, childhood friends, and cemeteries, to mention only a few. She’s funny, too, writing with an irascible, double-edged conceit reminiscent of the Countess of Die (the infamous troubadour poet), as in these lines from “What Do You Want From Me?”:

I could have said your heart,

pitchfork at the ready.

No, hands cupped.

Clasped. And hope to die.

Your hand, coat of arms, trombone.

The brass one.

I could have blown my nose

with the noisy insouciance you had come to expect.

I could have said love, duh. I could have said that.

As she did in her previous books, Bright Moves, Misery Prefigured, and Foiled Again, Rosser creates her own meter-making arguments in Mimi’s Trapeze. Her writing, to quote Whitman, “embraces the lesson of the past with calmness,” and adds subversion, humor, intensity, and wisdom.

Published on October 21, 2015