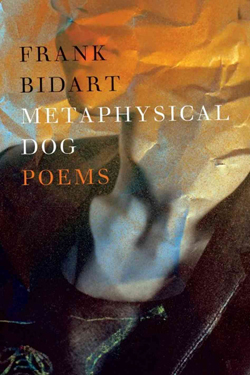

Metaphysical Dog

by Frank Bidart

reviewed by William Doreski

Frank Bidart’s poetry explores the tensions between emotional nuance and rhetorical expression. His elaborate punctuation, delicate and frequently enjambed line breaks, italics, extra white space, prose inserts, and jagged rhythms accommodate shifts in mood and expressive modes that, if not carefully delineated, would founder the poem on its internal conflicts. In the best-known of the earlier poems, such as “The War of Vaslav Nijinsky,” “The Arc,” and “Ellen West,” Bidart juxtaposes competing and self-complicating emotions in a dazzle of technical prowess. “Ellen West” (1977) exemplifies the edgy self-interrogation of these persona poems:

Bread

for days on end

drives all real thought from my brain. . . .—Then I think, No. The ideal of being thin

conceals the ideal

not to have a body—;

which is NOT trivial.

Bidart catches his speaker’s jagged thought-pattern not only with enjambment and white space but with varied levels of applied emphasis: italics, capitalization, and aggressive punctuation. In “The First Hours of the Night” (1990), he brings this technique to a peak, risking and sometimes inciting an emotional blitz bordering on hysteria:

I realized that on my back I was carrying

—HAD, carried

all my life,—the ENTRAILS, of my horse—;

In more recent years, Bidart’s work seems to be caught in the afterglow of that period of intense poetic emotion. Metaphysical Dog uses the same technical resources but in sparing and muted ways. White space, prose rhythms broken by abrupt enjambment, and the familiar stutter of fragmentation still shape these muffled, introverted poems. But he rarely wields the aggressive over-punctuation of the early work, which in unfamiliar combinations of dash, semicolon, and colon forced almost ineluctable nuances onto the reader. An elegiac tone and mood permeate the book, but do not account for all of its emotional colorings. The topics remain the familiar ones: the stress of growing up gay, the pain of his parents’ marriage, the self-abasement that began early and continues to haunt, the consolations (or discords) of religion and the arts. But the gentler tone and shedding of dramatic sonorities render these poems more intimate and emotionally accessible, if less jagged and forceful.

“Writing ‘Ellen West,’” the second poem in the new book, returns to that earlier work, examining in the third person the motives for writing the earlier poem and the author’s astringent relationship with his mother:

“Ellen West” was written in the year after his mother’s death.

*

By the time she died he had so thoroughly betrayed the ground of

intimacy on which his life was founded he had no right to live.

The calm analytical voice, distancing itself from the pain of the poet’s actual relationship with his mother, characterizes this new collection. Although “Writing ‘Ellen West’” is not the most impressive poem in this collection, a note at the end of the book underscores its importance to Bidart’s poetics:

The gestures poems make are the same as the gestures of ritual injunction—curse; exorcism; prayer; underlying everything, perhaps, the attempt to make someone or something live again. Both poet and shaman make a model that stands for the whole. Substitution, symbolic substitution. The mind conceives that something lived, or might live. Implicit is the demand to understand. The memorial that is ward and warning. Without these ancient springs poems are merely more words.

In keeping with this credo, all of the other poems embrace the shamanistic notion expressed in “As You Crave Soul” that “Words are flesh. Words // are flesh // craving to become idea.” The tension between embodiment and abstraction empowers the voice in these poems. The speakers move with alacrity between image and abstraction, lending the poems the grace of a mind moving between perception and process. “As You Crave Soul,” after considering the relationship among expression (poetry), the body, and the thought process, concludes that the ambiguity of that relationship is its strength: “When, after a reading, you are asked / to describe your aesthetics, // you reply, An aesthetics of embodiment.” Is, then, aesthetics—the making of poetry—sufficient to gloss the hurt, disappointment, and loss depicted in nearly all of Bidart’s poetry? “Dream of the Book” seems to suggest that unreadability might be preferable to being seduced by the idea of the book, yet concludes that the Book (that is, the idea, of the book) is culture in its greater manifestation: as both inheritance and the work of a lifetime.

“Whitman,” one of the major poems of this collection, and of Bidart’s work so far, engages the writer whose life and work together embody almost every possible aspect of human culture as subject, act, identity. Bidart depicts Whitman reading his own first version of Leaves of Grass: “He read with a still, unmelodramatic directness and simplicity / that made the lines seem as if distilled from the throat of the / generous gods.” These lines by Bidart may not even be lines (difficult to be sure from the page layout) but a single breath-unit, as Whitman might have uttered them. As Bidart notes in this poem, “A poem read aloud is by its nature a vision of its nature.” All poems are read aloud, even if silently, by both their readers and authors, and so the vision of the nature of all poems is the essence of their aesthetic: an embodiment. No one has better expressed the singular way in which poetry envisions itself—that is no one has expressed it more clearly than Whitman has, through Bidart.

Further, this voice embodied in the poem is also a gaze “ruthless” enough to “queer me in adolescence”—which means not only to confirm the speaker’s gayness but to bend him into the aesthetic vision that has sustained him through a life of emotional tension and displacement. This is not a vision of poetry as healing power but rather as a means of facing up to the emotional, perceptual, and imaginative complexities of our lives. “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” Eliot observes in concluding The Waste Land. Bidart’s even more fragmented poetry still constructs a formidable vision of strength in the stress of adversity: “our own sweet sole self like debris smashed beneath your feet at the sea’s edge,” he observes, invoking Whitman’s “Sea-Drift” poems.

The shorter poems in the collection also benefit from the easing of rhetorical tension. Calmer, more meditative now, these poems may seem a little more conventional than Bidart’s earlier work, but they are surer, more focused, and with a firmer grasp of their emotional insights, even or maybe especially when they end with lines like “When he wasn’t looking / the earth turned to mush” (“Late Fairbanks”). Bidart has now had a long poetic career, but he is still developing and refusing to repeat himself. His ear for emotional rhetoric is still fine-tuning itself, and his poems with their complex, delicate structures still compel and surprise.

Published on October 22, 2013