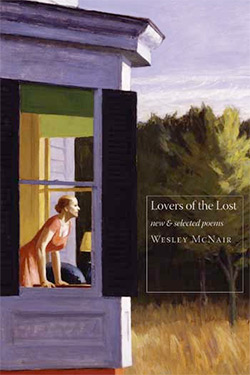

Lovers of the Lost: New & Selected Poems

by Wesley McNair

reviewed by Kevin T. O'Connor

I can imagine Wesley McNair’s poems waiting for a long time in the plush reception area of a big New York magazine or publishing house. However well-spoken and well-groomed, they are wearing mud boots and canvas work shirts, and they seem, well, out of place in this setting. They don’t have an appointment and they don’t know the right people . . . but they are too substantial to turn away completely. So they sit and wait for a while and then quietly go back to work until they eventually appear in a beautifully presented collection by the estimable New England publisher, David R. Godine.

If it is true, as William Carlos Williams writes in “To Elsie,” that our local citizens can be “tricked out” at night “with gauds / from imagination / which have no / peasant traditions to give them / character,” many of Wes McNair’s poems address this very absence with a defining imagination, memorably delineating the lives of middle- and working-class people in rural and small-town New England. Even sample titles, “Small Towns Are Passing,” “The Last Time Shorty Towers Fetched the Cows,” or “Reading Poems at the Grange Meeting in What Must Be Heaven,” suggest these poems’ always compassionate, sometimes pained or humorous evocations of a back-roads culture too often neglected in the speed and glare of a more glamorous America.

. . . I’m the one waiting

in line behind the couple with the skis

on their minivan who don’t even notice her alert,

genuine eyes, on their way through Eyeblink,

Maine, to someplace they’ve heard of . . .

(“My Town”)

The title of the collection, Lovers of the Lost, highlights the elegiac key of the volume, which includes directly autobiographical poems such as “Hearing That My Father Died in a Supermarket” and “After My Stepfather’s Death.” This poetry also laments the invisible passing of a way of life intimately connected to a sense of place. McNair’s work often relies on anecdotal narrative to carry it to modest epiphanies, where complex but always clear syntax stays in meaningful tension with its linear sense, as when the speaker imagines his mother seeing her husband’s hand above his crushed body:

. . . It is so quiet here, she begins

to think all over again about the fight

they had, their worst, on the evening

she found him, how Paul kicked the dirt

in the greenhouse and cursed it, then

cursed her for binding him to it,

and afterward how quiet it was around her

in that place, too, until at last she walked

out by the barn to the source of the silence,

which was the dropped car, and beneath it

his upturned hand, opened in welcome

as if to taunt her.

(“My Mother Enters Heaven”)

The positioning of elements alone, especially the threading of “quiet” and “silence,” make the sentence a miniature of narrative suspense and economy, and the ease with which it rolls off the tongue reflects another underestimated art: creating an illusion of naturalness.

McNair’s poetry never condescends to its subjects; neither does it flatter its imagined readers or dare them to follow him into some abstruse modernist maze. The poet is driving—no doubt about that—and he is shaping our attention through formal selections and quiet music, but he speaks to his readers as if they are on the same plane of perception, perhaps new neighbors or visitors sitting beside him in a car:

The main streets of towns

don’t go uphill,

and the houses aren’t

purple like that

tenement with one eye

clapboarded over. Never

mind how it wavers

backward, watching you

try to find second gear.

You’ve arrived

at the top of the town:

a closed garage

where nobody’s dog

sits, collarless,

and right next door

a church which seems

to advertise Unleaded.

(“A Traveler’s Advisory”)

Those who would dismiss him as formally unambitious might underappreciate the simple enjambment “you / try,” which somersaults the point of view, or the quick concision of images—garage, dog, church, gas station—which evokes a specific world of habits and rites and values. McNair’s work at its best offers a stylistic transparency where the poem’s language and form—its plain but careful imitative diction and tempo-determining line breaks—are always vehicles to insight, not primarily features of a performance calling attention to itself. In “The Last Time Shorty Towers Fetched the Cows” the poet’s “us” comes off as inviting, not coercive or presumptuous.

. . . Let us imagine, in that moment

just before he turns to the roof’s edge

and the abrupt end of the joke

which is all anyone thought to remember

of his life, Shorty is listening

to what seems to be the voice

of a lost heifer, just breaking upward.

Some of McNair’s best poems remind me of the mid-career work of James Wright, conjuring epiphanies in the scarred, hardscrabble mill towns of the Midwest. But where Wright’s empathic imagination seems removed and isolated, in a kind of ghostly alienation from its marginal, working-class subjects, McNair’s poems feel more grounded, written in the voice of an insider—less like Frost’s poems of lonely field walkers and more like Heaney’s poems about farming people, with whom he is still happy to identify.

And this poetry is often funny. The key to the humor is a point-of-view elastic enough to inhabit a dog who, in the poem “Sleep,” sees us “looking into a humming / square of light” and understands that “we are not looking, exactly, but sleeping / with our eyes open, then goes to sleep / himself.” Furthermore, titles like “Hymn to the Comb-Over,” “Love Handles,” or “Poem for My Feet” show authentic self-deprecation (the big feet are apparently McNair’s) and insightful bemusement.

This is poetry that seems to know its proper scale and rarely, if ever, overreaches. Still, its mundane autobiographical materials, as in mid-career poems like “The Good-Boy Suit” or “Shovels,” occasionally rely too heavily on one metaphorical image to redeem memories of the poet’s upbringing. But when such materials are worked fully into the social context that is McNair’s metier, as in “The Boy Carrying the Flag,” or when the personal is refracted away from self, as in the movingly elegiac “My Mother Enters Heaven,” McNair’s work demonstrates that personal or “confessional” poetry belongs as much to the people of “Don’t Blink, / Can’t Dance, / or Town of No” as it does to Robert Lowell, who only summered in Maine and who could claim representative material as part of his ancestral birthright.

McNair’s work does not try to shift any paradigm: it does not push language or form—or consciousness itself—toward any radically experimental presentations. But if he does not follow Pound’s modernist imperative to “make it new,” he does succeed in making a poetry that is recognizably and distinctively his own and a poetry that many readers will recognize as their own.

Published on March 18, 2013