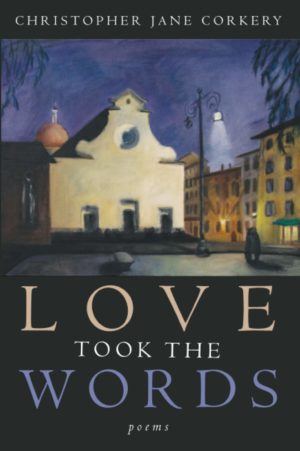

Love Took the Words

by Christopher Jane Corkery

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Thirty-five years after her lauded debut collection, Blessing, Christopher Jane Corkery’s superb second book, Love Took the Words, extends her commitment to musical, allusive, formally inventive poetry, which draws on religious and literary traditions as well as daily life.

“Upholstery” puts this commitment into words with its witty evocation of a sagging past upheld by artistic form.

I love to say upholstery—what a ridiculous word!—

conjuring uphold and holsters, Poles

who’ve held me, bras and jock-straps holding up,

leather straps from subway crossbars

the summer of sixty-six, the sweat at eighty-ninth

The poem smartly weaves together the violence of the old gothic ballad, “The Highwayman,” with the story of a local upholsterer from Barbados who carries a gun, along with neighborhood church services and the speaker’s account of childbirth. The result is a design not easily explicated, but readily enjoyed. “Come,” Corkery invites us, “Rest on the couch I’ve made. / It holds up well.”

This deft balancing of the sacred and profane energizes much of the collection. In “The Woman at the Tijuana Dump,” the speaker describes cartography lessons at the Sacred Heart convent school; the map’s “tricks of colored water” help her understand God as a “creature of the border.” This borderland is also home to

the woman in the Tijuana dump

who spoke as a god when the visitor asked her if

he might take home a shiny thing as artifact.

The “sturdy” woman, vividly portrayed in “acid-frayed boots / blue sweatpants, a stained purple shirt”

… wore rubber gloves and she opened her arms

wide, as she turned around and said

Of course, this is the dump, there is enough

for all.

Amid the mass of objects discarded from our lives, the priestess of the pit encourages acts of recovery, collection, and recognition.

Corkery takes on the big subjects of faith, love, evil, and God, in order, as she puts it, “to feel God’s love as motive.” Although respectful of the Catholic church and her parochial education, she enchants us with stories of daring students like Caroline (“At a Covent School North of Paris”), who climbs out of the dormitory window and into a tree.

High enough, she could not be brought down for a day,

not by shout nor imploring, nor the Reverend Mother’s

hissed vow to expel. We, her friends, were jealous,

but also admiring. We watched her black hair be obscured

by blossoms. They were pear and white. So little to do

in tiny Gouvieux. So many myths to revise.

Caroline’s brief liberation from the solemn school represents an important goal of Love Took the Words—to transform boredom into something playful and more meaningful. Take “Things”:

Hello, says the paper.

Hello, the hat.

Pick me up, read me,

Put me on.We wait with the clock,

And the kettle, and the long

Breadknife whose handle

Is silky with age.

This critique of naturally observed and metrically constructed notions of time is also deployed in “Patio,” which first appeared in The Atlantic. “Patio” offers a wry take on backyard projects, with a nod to Andrew Marvell’s “a green thought in a green shade.”

To this green shade

I won’t admit

Defeat, or heat

Or an angry clock

Outraged at having

No time to tell,

Or love embarrassed

Because unanswered …

The author’s love for poets is certainly answered in this collection. There are conversations with and about Dante, Teresa of Ávila, George Herbert, John Keats, Emily Dickinson, and William Butler Yeats. “My head is storms at morning / With all the things I’ve read,” Corkery writes. The villanelle “It Was Yeats Who Took Me” remembers the excitement and awkwardness of teenage romance, only surpassed, it seems, by the speaker’s true passion for the Irish poet and his influential work.

It was Yeats who took me. I was seventeen,

In love with watery consonants, with boys.

But Yeats would show me what my life could mean.

Corkery’s faith in the transformative, redemptive power of poetic language is tested and upheld, especially in dealing with the death of her husband. In the vivid and moving love poem “Torn Paper,” we learn about a trip to Paris the couple took after his recovery from lung cancer surgery. Corkery remembers coughing, rain, geraniums, short walks, and her husband bringing her a “tiny paper cup, one inch full / of espresso.” This gesture leads to a small ritual—“I added sugar, an inch of milk”—and the vision of a diminished but promising sky, which lifts her love.

the sky a torn bit of paper

in the door’s high glass. My God,

the happiness love restarted brings!

Love Took the Words is neither an artistically nor a politically earthshattering collection. What it does show is that traditional forms and finely wrought language, with the right blend of erudition and emotion (and a bit of wit and fun), can still speak powerfully to readers today.

Published on July 27, 2021