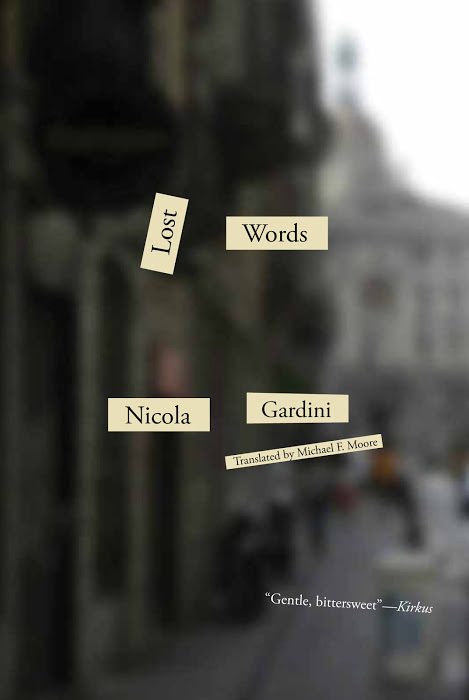

Lost Words

by Nicola Gardini

reviewed by Victoria Zhuang

Intellectual irony and congested garbage chutes. Bumptious, quarreling, scandalmongering tenants in a building on the outskirts of Milan during the 1970s. A dictionary; an education; a social fabric torn. This is the world of Lost Words, Nicola Gardini’s rough-hewn jewel, the spirited, sad novel of an Italian childhood lived among books and neighbors at war. Gardini has a confident touch that transfers well to his characters. Some are merely sketched out, but all of them, as they squabble or try to make community together, expand with passionate conviction. Gardini relates their dramas at Via Icaro 15 through the doorwoman’s shy teenage son, Luca, in a boisterous style that, like a well-groomed cat, alternately bites, leaps, delights, and demurs.

Luca means “son of luck,” but at the time his story begins, everyone calls him by the nickname Chino, which means “bending toward the ground.” The irony is that Gardini hardly gives him any luck: on the eve of Chino’s thirteenth birthday, burglars attack a neighboring place and frighten the propertied women living upstairs, who until now have co-existed tolerantly enough with Chino’s working-class mother, Elvira. “We can’t tolerate this violence!” they protest. “Burglary is rape!” They demand that Elvira guard the building at all hours of the day. In time, their impositions grow. When Elvira resists, they conspire against her. Chino’s father, a factory worker who quarrels with Elvira and treats her for the most part dismissively, offers little help, and while Chino begins to take English lessons from a new recluse upstairs named Miss Lynd, whose offer of friendship and cultured mien give him hope for a better existence, his mother’s life continues deteriorating. Gardini contrasts the idea of winning la fortuna, luck, with the reality of Chino and his mother’s earthbound situations, and this deep opposition advances the plot in a way that feels grounded even while some events, such as the appearance of a travelling salesman who peddles genuine diamonds to Elvira, seem fanciful.

Despite this dingy background, the frankness and rough warmth of Chino’s narration are uniformly refreshing, as are the unpretentious expressive liberties Gardini takes. One chapter begins with a train of onomatopoeia: “CLICK CLICK CLICK CLICK … CLICK CLICK click click click … Hunt and peck … click click click click … Ding!” The sound of these repetitions has an oddly soothing effect, suggesting the aloof yet methodical inquisitiveness of their originator, a man with a troubled relation to Miss Lynd who arrives later at Via Icaro 15.

Gardini subtly criticizes and sympathizes with everyone in his book, even Chino’s neighbors, frightful hens who fidget at the thought of their eggs being seized. He acknowledges the childishness of Chino’s mother, who wants an apartment of her own: “The time has finally come for us to buy a house, too! Happy New Year! Viva the new house! Viva 1973!” And he humanizes Chino’s father at some moments: “My father didn’t have the courage to contradict her, so he stroked her hair tenderly.” Even Chino’s beloved, self-assured Miss Lynd, who calls him Luca, turns out to be by turns fragile and elusive.

The critic Lionel Trilling once said Lolita was a love story: though it had nothing like romantic reciprocity, it gave substance to somebody’s half-illegible dream of loving and being loved. Lost Words is a love story of this same kind. Here the formula of boy-meets-girl is supplanted by the vision of several people living in close quarters who do not love each other, or do not allow themselves to, a predicament that Gardini sees in Italy and Europe on the whole. At the level of language, Gardini often sublimates the violence of nations into a caustic comedy of ideas, the energy of which comes across fully in Moore’s crackling English translation. He blends his characters’ predicaments with the woes of their generation, a lost generation of unlucky youths and would-be leaders. While the feeling of unceasing strife comes increasingly to dominate the secluded world of their apartment building, dark clouds move overhead: rumors of labor movements, women’s rights, and political unrest rear their heads on occasion.

Miss Lynd remarks to Luca in conversation, “If there really were an Italy, would the Italians really be so divisive, so egotistical, so deplorably vain? Dov’è il popolo?—Where are the people?” Where indeed, one might ask? In Gardini’s novel, with its generous call to greater interpersonal understanding, one answer seems to be: everywhere, hiding unspoken, waiting.

Published on August 23, 2016