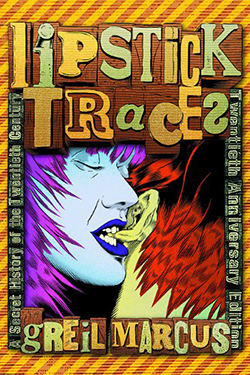

Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century

by Greil Marcus

reviewed by Cameron McWhirter

For a time in the early 1990s it was hard to walk around Lower Manhattan without running into someone, usually a scrawny twenty-something, gripping a chunky yellow and orange paperback titled Lipstick Traces. The book’s cover featured a stylized photograph of a bug-eyed Johnny Rotten.

That twenty-something could have been me. This was in the time before laptops and cellphones, and we sat in squalid apartments or Alphabet City bars discussing politics and music. We were suburban refugees raised on Punk and post-Punk rock; we had spent years listening to The Clash and the Gang of Four. We trolled shabby, independent bookstores—when such places still were common—searching for cheap copies of Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life, Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, or booklets by Peter Lamborn Wilson. We saw consumerism and pop culture as twin monsters. Aspects of our disaffection were fatuous, but at core it was genuine. We were alienated.

Then Greil Marcus gave us Lipstick Traces. It was ostensibly a book about Punk music. In fact, the book was an elegantly written narrative history of twentieth-century artistic rebellion, from the art movements of post-World War I Germany and the Situationist collectives of 1960s France to the yowling Sex Pistols. It captured and conveyed not just a fleeting subculture but a genealogical tree of fleeting subcultures. Marcus wove the ephemeral threads together with such skill that his book gave these rebellions a permanence and a strength that the rush of time had never allowed them. It would be difficult to underestimate the importance of Lipstick Traces for a generation of punkers, or slackers, or whatever we were. It placed our view of modernity on a continuum of thought. It gave alienation a historical context.

Marcus now is garnering attention, if not universal praise, for the recently released A New Literary History of America, the behemoth he co-edited with Werner Sollors. Happily, Harvard University Press has used the occasion to re-issue Marcus’s past work, including Lipstick Traces. I remember being amazed that such a book had been published by the same publishers that brought us the Loeb Greek and Latin classics. Twenty years later, I’m glad it’s being reissued; good writing demands rediscovery.

Marcus opens Lipstick Traces with crafty modesty by stating: “This book is about a single, serpentine fact: late in 1976, a record called ‘Anarchy in the U.K.’ was issued in London, and this event launched a transformation of pop music all over the world.” But the book is much more than that—it is a history of the fleeting rejections of mass society that occur, and have always occurred, as our culture has swelled into the voracious everythingosaurus it is today.

The author starts with a single concert: the last performance by the Sex Pistols at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom on January 14, 1978. The concert ended a disastrous American tour for the British group and ended the group as well. For Marcus, that implosive performance, which he witnessed, marked both the apogee and nadir of the band’s existence. As Marcus sums up, “They used rock ’n’ roll as a weapon against itself.”

A look back at history leads Marcus to medieval Europe and the Ranters and other heretics who set up subcultures on the fringes of society. He explores rebellious art movements at the dawn of the twentieth century, including the Dadaists, German artists rejecting mainstream art for chaos and random beauty in the shell of Weimar Germany. He describes French intellectual movements that critiqued modern society with anarchic performances and disjointed films in the 1950s and 1960s. And he connects them all to Punk. Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren had seen student riots in Paris in 1968. He learned about Situationism, the Marxian intellectual movement that fed a nationwide revolt. In the 1970s, he funneled these ideas into Sex Pistols’ lyrics.

Marcus quotes the musician Paul Westerberg as saying that he became enthralled with the Sex Pistols because “It was obvious that they didn’t know what they were doing and they didn’t care.” That statement is the core belief of all the movements that Marcus explores. He artfully shows that this is not a declaration of nihilism but a striving for liberation from what the Situationists called “The Spectacle.”

The Spectacle was the all-devouring beast of modern society, which blinded wage slaves with the fetishism of commodity culture. According to Marcus, as the Spectacle metastasized in the twentieth century, movements rose again and again to mock it, reject it, and attempt, however briefly or unsuccessfully, to overthrow it. When the Dadaist Tristan Tsara cut words out of the newspaper, shook them up in a bag, and pulled them out randomly to form a poem, he was creating anti-Spectacle art. When the Sex Pistols performed on stage, they were going for the same thing. Tsara’s answer to critics would be the same as a punk rocker: Fuck you, we don’t care what you think.

Two decades after its first publication, Lipstick Traces still stands as an important history of rebellion and art. Of course, the Spectacle ultimately consumed and killed Punk, but Marcus offers an insight into what Punk promised: a fleeting escape from the consumerism that overwhelms us, more now than the Situationists or Punkers ever could have imagined.

Published on June 21, 2013