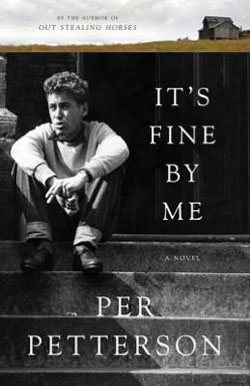

It’s Fine By Me

by Per Petterson, translated by Don Bartlett

reviewed by Joseph Holt

Here’s an idea: a person might prevent himself from becoming a victim so long as he’s willing to defend himself, or even strike first. This idea of proactive resistance—physical, but even more so emotional—is at the core of It’s Fine By Me, Per Petterson’s second novel and the most recent from his backlist to be translated into English.

Originally published in Norway as Det er greit for meg in 1992, It’s Fine By Me is narrated by Audun Sletten, a troubled-yet-resilient teenager. In summary, the novel sounds like a standard coming-of-age tale: Audun escapes his distant, alcoholic father and makes decisions that vault him into independence. But It’s Fine By Me is much more than that. It’s also a suspenseful story about eluding one’s ghosts, as well as a study in the dogged refusal of grief and in machismo as a method of self-preservation.

Structurally, It’s Fine By Me consists of two periods: when thirteen-year-old Audun flees with his mother and siblings from their rural home to an urban flat in Oslo; and when eighteen-year-old Audun leaves school to work as a laborer at a printing factory. In the interim, Audun’s father has disappeared, his younger brother has drowned, and his older sister has begun her own family, leaving Audun and his mother alone in a flat in Veitvet, a working-class district of Oslo. One morning while delivering newspapers, Audun chances upon his father, unkempt and carrying a rucksack, having just wandered in from the outlying forests.

Petterson creates in Tormod Sletten a fully realized adversary—an abusive father who is nonetheless capable of great tenderness. His long absence and unexpected return cause Audun to turn inward, to become emotionally wary. Yet, refreshingly, Audun resists self-pity, coping instead by cultivating a posture of calculated indifference, hence the novel’s title.

One early scene illustrates Audun’s burgeoning isolation. After his only friend, Arvid Jansen—the same Arvid Jansen who appears in Petterson’s later novels To Siberia and I Curse the River of Time—is suspended from school, Audun searches for him in a nearby forest. Once he sees Arvid, though, the two of them feel momentarily like strangers:

For a moment there, it’s difficult to be the one who is approaching. I almost turn and go back. He stands quite still watching me. . . . I feel like going back. This has never happened before. Not with Arvid. He is my friend, we have been friends for five years . . . and now here he is, watching me approach, and I do not know who it is that he sees.

But it’s only a moment, and then things fall back into place, he raises the hand holding the book and I wave back, and what I’m thinking is, I will always get by on my own.

It’s this stubborn defiance, resilience masked as apathy, that best characterizes Audun. He’s a loner, a non-joiner, thanks to the losses he has endured, and reticent to invest himself in others. This determined independence can sometimes make Audun appear feral, almost hostile—yet not without loyalty or compassion. For instance, partway through the novel Audun and Arvid seek out a gang of peers who have assaulted Arvid’s father at the Metro station. They find the assailant at a local bar and Audun drags him off his stool and out into the street. It’s a poignant, surprising scene, told with Petterson’s stark economy, delicately melding humor and violence.

Labor, too, comes to define Audun for the way it brings him honor. Like most of Petterson’s work, It’s Fine By Me is imbued with working-class pride. There’s terse poetry to Petterson’s technical descriptions of running a web press, as well as the brash, selfless men who work in unskilled positions. And as with Petterson’s later work, It’s Fine By Me contains vivid descriptions of the Norwegian landscape, of cold wind that blows from the sea and boulder-laden rivers that wind through the valleys.

It’s Fine By Me is a slim novel, only 200 pages, yet it manages to be rich in its evocation of youth and generous in its portrayal of surmounting grief. Not that Audun Sletten would ever confess to thinking in such terms. Rather than wear his emotions on his sleeve, he puts on the armor of indifference: “It doesn’t matter,” he says throughout the novel, “I really didn’t care” and “I don’t give a shit.” They’re tough statements which by their defiance protect Audun from the trials of adulthood, but which also betray his sheltered sorrow and his touching vulnerability.

Published on May 22, 2014