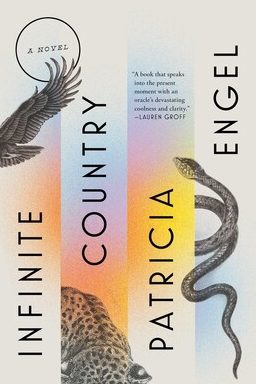

Infinite Country

by Patricia Engel

reviewed by Gina Isabel Rodriguez

Infinite Country is Colombian-American writer Patricia Engel’s masterful fourth book. This deeply empathetic novel charts one family’s years-long struggle to reunite after immigration laws have wrenched them apart.

As the book opens, fifteen-year-old Talia escapes from an all-girls’ correctional facility in the mountains of Colombia. She’s determined to cross more than two hundred miles to get to Bogotá, where her father has her plane ticket to the United States. The flight leaves in less than a week. This might be her only chance to reunite with her estranged mother and siblings in New Jersey.

As Talia hitchhikes toward the capital, Engel unfolds her parents’ story. Mauro and Elena are young lovebirds with few prospects in chronically violent Colombia, “where it felt impossible to get ahead if one wasn’t born to a certain class, rich or corrupt, or talented and beautiful enough for fútbol and farándula.” In 2000, they head to Houston with their first daughter, Karina. They plan to earn US dollars and return to Bogotá in six months.

Circumstances converge to rewrite Elena and Mauro’s decision. Faced with the latest violence in Bogotá and the birth of their son Nando, they overstay their visa. They fall into a cycle of seeking work and dodging immigration authorities. They have left behind the limitations of one country only to find themselves confined again.

Shortly after Talia is born, Mauro’s sudden deportation forces Elena to make a choice. She can’t care for a newborn and work. So she sends Talia to Colombia. Though Elena plans to bring Talia back soon, fifteen years pass. The youthful decision to seek opportunity abroad has evolved into a question neither Mauro nor Elena can answer—will the family ever be whole again?

While Talia’s precipitous journey provides the novel’s through line, Mauro’s stories from the indigenous Muisca tradition are its thematic ground. Through these myths about the Colombian landscape and its animals, he reminds Talia that there was a time before colonization. There was a time when these continents were borderless.

Engel uses plain, natural language to untangle the family’s history. The lack of embellishment lends an unflinching frankness to Infinite Country. Consider Elena’s observation about her young children: “Karina and Nando already knew to fear police.” These eight spare words drive home a bald truth—that even as children, they understand and fear family separation. In later chapters, Engel gives us Nando’s and Karina’s first-person narratives in raw, conversational language. Karina writes, “I hate the term undocumented. It implies people like my mother and me don’t exist without a paper trail … Don’t tell me I’m undocumented when my name is tattooed on my father’s arm.” The writing is fiery; it’s reminiscent of Engel’s vibrant first book Vida (2010).

When she does elevate the language, Engel gives startling dimension to her characters’ emotions. Elena’s “love for her own children is different, marrowed beyond bloodlines, picked from their terrain, dusted off their mountains. In their dark eyes and amber skin she sees her cloud-cast city; her ancestors, her mother, everything her family has ever been and ever will be.” The language draws together earth and sky, past and future; it suggests the cosmic. In Infinite Country, love is magic. It’s the only way Talia’s family has to ward off distance and separation.

Engel’s work broaches questions fundamental to the immigration experience. Was it right to leave home? Was America the right choice? Young Mauro and Elena grew up in a “time when the Andean air tasted of gunfire.” Their children face unchecked xenophobia, mass shootings, and the caustically anti-immigrant policies of the Trump administration. “What was it about this country that kept everyone hostage to its fantasy?” In both Colombia and the US, Talia’s divided family finds sorrow and joy. Engel convincingly articulates the fears and hopes that keep her characters cycling between wanting to stay and wanting to leave.

Infinite Country feels searingly timely. Reading it in early January, I reflexively connected Nando’s observations to the events at the US Capitol: “I remember wondering what it must feel like to belong to American whiteness and to know you can do whatever you want because nobody you love is deportable. Your worst crime might get you locked up forever but they’ll never take away your claim to this country.”

But, I think, calling this book “of our time” would be missing Engel’s point. Engel’s gorgeously woven novel challenges us to consider that the United States has always been a place of borders: the ones drawn onto the landscape, those written into statutes, and those we imagine between us and them. For too long, our national narrative has ignored the question at the heart of Infinite Country: how can one family’s wish to be together be too much to ask for?

Published on April 23, 2021