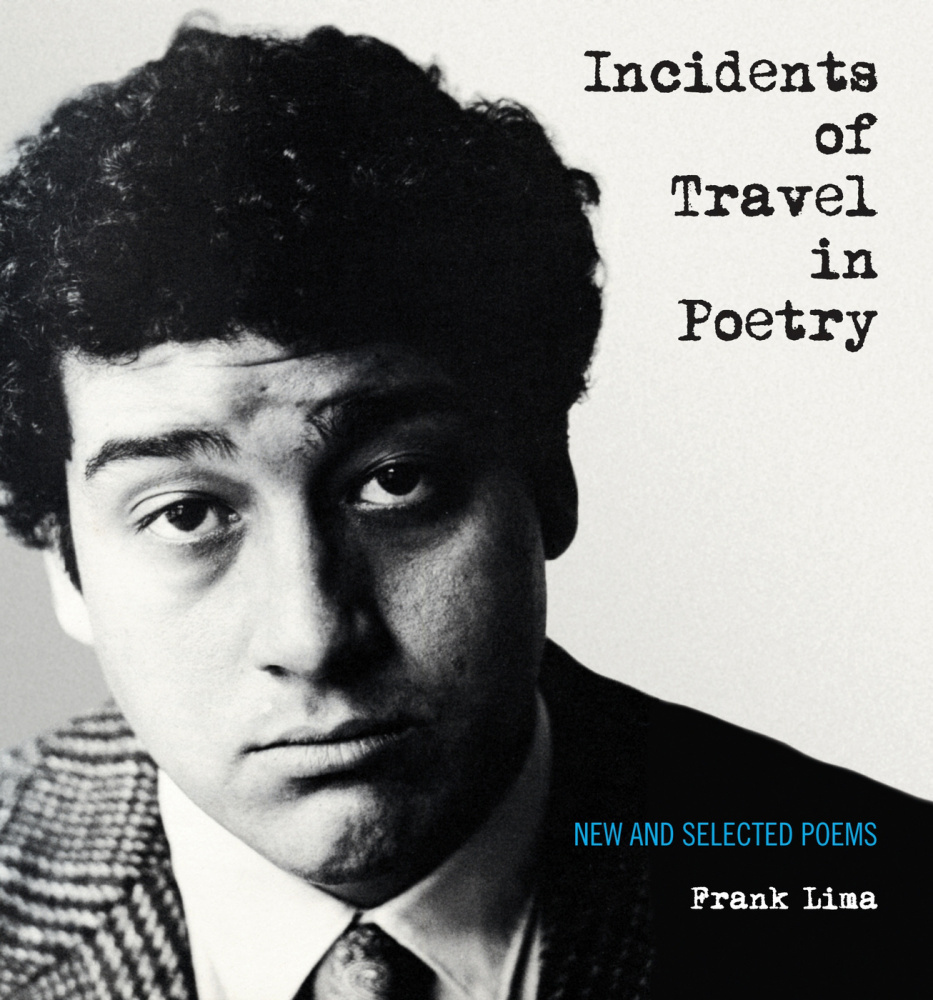

Incidents of Travel in Poetry: New and Selected Poems

by Frank Lima

reviewed by Nico Alvarado

There is a species of longing endemic to fans of a certain kind of artist: the haunted hunger for the lost archive, the hidden trove. The ghost of the missing work cries out to be recovered. The artist’s acolytes decry the bastards who keep the work under wraps; they dream of discovering old notebooks in an attic upstate, of prying open dusty crates and standing in that glow.

Frank Lima is one such artist. A visionary New York School poet, and the only Latino on the scene, Lima made a splash on the East Village in the sixties—boozing with the de Koonings, collaborating with geniuses, knocking dudes over tables—and published a small handful of much-admired books before falling into obscurity in middle age. Despite his powerfully evocative work and close kinship with legendary poets and painters, Lima died unheralded in 2013, and it has taken some time for his reputation to catch up to his brilliance. With the publication of Incidents of Travel in Poetry: New and Selected Poems, writer-editors Garrett Caples and Julien Poirier have set out to change that. This scrupulously edited edition, compiled with the aid of Helen Lima, Frank’s widow, makes available the wide range of Lima’s oeuvre and establishes him as a great American poet. It also finally opens the lid on the vast stores of work that have been hidden from view until now.

Lima’s trajectory as an artist is marked by restlessness. His earliest poems—sharp-edged, pitiless, psychedelic accounts of gangster life in Spanish Harlem—are devastatingly assured, deserving of their own place in American letters:

I come to you

as always

green

tired

need a shave

a bath

I stink

unlock the nights

in jail

it’s spring on the windows

my heart

in a bag

and some beer

Hi Monkey

I’m home

(“Primavera”)

But the bulk of his work far outstrips his violent youth. (Necessarily so: in an interview with the poet and translator Guillermo Parra, Lima noted that “in order to continue writing poetry about the life I was leading would have been certain death. I mean the cemetery kind …. ”) Instead, he strikes out again and again for undiscovered territory, always in pursuit of immediacy and strangeness, a truth beyond the realm of fact. Like his friend Joseph Ceravolo, Lima is a surrealist of everyday life, his images and similes built around the illogic of dream, non sequitur, and joke. Unlike the syntactically explosive Ceravolo, however, Lima generally works in a plainspoken declarative mode. Although their grammar is familiar and approachable, the words in these declarations are charged with mystery, taking on the force of revelation, as in “The Future”:

There is

A white fish turning on its stomach

Pressing great things against my pants

Like an animal made of snow

It would be terrible if I were the sun

Melting her on everyone

Season after season

I am born a son

What if after

So much eternity

I outlived her?

My son would be the darkness

Between the seasons

The imitations of moonlight

No

He would be the fortune teller’s mirror

In a coffee cup

The last hallucination of the hunted fox.

These are not poems that have much truck with the manners and methods of traditional craft. (In “Urbane Parables,” he notes mordantly that “There is a poetic life in American poetry, ask Helen Vendler. / Just pay your electrical bill. Speak English.”) Both in his art and as an artist, Lima chose always to locate himself outside of the expected and the accepted. Throughout his life, he refused to kowtow to the various communities and kingmakers who would have liked to affix a label—“Latino poet” on one hand, “New York School poet” on the other—to him or his work, and he felt that he had paid dearly for his integrity. At the same time, Lima proudly claimed every last strand of his ethnic and artistic heritage. It is a slender needle to thread. He held devoutly to a poetics of transcendence, to the almost quaint notion (expressed in a Q&A with the Poetry Society of America) that “Nationality and gender do not exist in good poetry,” even as his own good poetry is hugely informed and enriched by his many identities: half-Mexican and half-Puerto-Rican father, lover, tenderhearted New York tough-guy artist-chef from the barrio. He refuses everything and claims it all at once.

Lima’s outsider practice only deepened in his later years. Having removed all manner of monkeys from his back (heroin, alcohol, childhood trauma), he wrote a poem a day for many years. This flood of late work was provoked or permitted by a convergence of factors: sobriety, a stable marriage, the discovery of Peter Elbow’s pedagogy of freewriting, the death of his friend Kenneth Koch and a concomitant vow to poetry. Perhaps, above all, simple happiness. Whatever the source, fully half of Incidents of Travel in Poetry is composed of poems written between 1997, when his last published book came out, and 2013, the year of his death, and they were years of intense creative production.

Late Lima sprawls. Often written in bursts of prose that he shaped afterwards into long-lined regular stanzas, the poems’ visual tidiness is constantly undermined by an itchy linguistic wandering, as in “Before the World Ends,” which begins:

Sometimes a spider’s thread will appear like some magical human organ,

The young woman of your dream, or your favorite shirt.

Nevertheless, it is time for a Sunday morning instead of the secret room

We share with the end of sorrow: The bleeding label on the heart is

Already tomorrow to the evening stars that appear tame as they watchOur unadulterated atrocities and benign cruelties inside the name of a

Marble wedding cake with the tower of Babel on the top.

This audacious confection was made with a million nails that represent

The strawberry-colored past of someone’s life you envied.

That is how the world began, like a funny little bright spot in the sky.

Prolixity is not a bug in these poems; it’s a feature. Lines don’t progress so much as swerve, each new word or image spun off sidewise by way of relentless modification and subordination. In his introduction, Garrett Caples describes late Lima thus: “Frequently untethered to any recognizable, realistic scenario … the poems move matter-of-factly, almost effortlessly, from assertion to assertion, with no obvious sense of logical development. Yet they seem the opposite of random phrasemaking, instead motivated by an inner emotional necessity.”

The necessity becomes our own. At last to live in these poems: “Hi Monkey / I’m home.”

Published on October 25, 2016