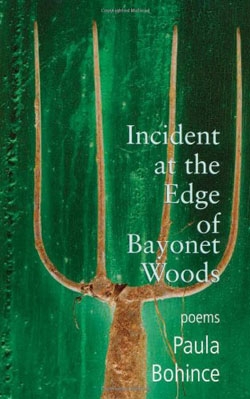

Incident at the Edge of Bayonet Woods

by Paula Bohince

reviewed by John Hennessy

Paula Bohince’s debut collection, Incident at the Edge of Bayonet Woods, ranks among the darkest and most disturbing books of poetry published in this country in the last decade. The pitchfork tines on the cover suggest both the latent menace in the title and a detail of Grant Wood’s painting, American Gothic. It’s unclear how much irony, if any, is intended by this, but the subjects and settings of these poems are certainly stalwarts of the gothic: rape, incest, murder, suicide, collapsed and abandoned coal mines, ruined barns, an isolated farmhouse. But Bohince’s lyrical gifts, especially her ability to create vivid landscapes with a few precise strokes and the fact that she tells her story obliquely, keep the book from being overwhelmed by its subject matter.

Incident at the Edge of Bayonet Woods is presented as a murder mystery—a novel idea for a book of poems. The story’s narrative structure is closer to mosaic than most suspense literature, however. Bohince offers multiple first-person speakers in the collection: each of three farmhands gives his own “Gospel” account of the killing. About halfway through, in the most striking of these, the murderer confesses:

When the wet rose bloomed

in the chest of the man I killed, I tried to concentrate

on its image,tried to sit with that flower and feel

as God must:the pleasure of His birds swollen with feathers,

His birds bound to His sky,belonging to His kingdom of violence.

As it turns out, the murder is only one of several crimes in this book. The story’s setting is a farm in western Pennsylvania, where “crabgrass thickens, and catalpas bloom / gigantic, hoping to hide our homestead, the poverty / and grime that kept us mired here,” and the principal narrator is the daughter of the dead man. Of course, western Pennsylvania stands in here for any number of rural sites, and this doubling of place is mirrored by the proliferation and overlapping of personae and voices in the collection. The farmer’s daughter and her friend Marie are connected by grief and seem to have much else in common, though how much, exactly, is unclear. Marie “can tell / she’s been touched, if not the how, / not the when, though she senses the riddle / lies with her father— / . . . the opaque memory making her choose / herself over him.” But the uncertainty is resolved in the last poem, “Charity,” which leaves no doubt that she has been the victim of incest.

This, in turn, suggests another possibility: has the unnamed narrator also been abused by her father? In “Toward Happiness” she says of him, “I loved one person all my life.” But a few pages earlier, when she thinks “of love,” she unsettlingly sees her father’s murderer. In “Still Life with Needle,” she mends her nightgown, “torn / at the shoulder where I leaned hard against / a sycamore, waiting for a comet, / then falling asleep, // feeling myself carried to bed, waking / with dirt in my mouth.” The imagery suggests a further connection to Marie and her father—and that may be the point. Grief has overwhelmed this woman and her father is present everywhere, both before and after his death. In “The Fatherless Room,” she stands over the bloodstain at the site of her father’s murder, her thoughts full of strange and challenging echoes of his murderer’s voice: “If this were spring, there would be more birds / to look at. My birds, I would think, / in these trees that were his.”

While the book’s primary mystery is cleared up quickly—three farmhands have robbed the father, who doesn’t trust banks, of his life’s savings and one has shot him—many unanswered questions remain. This is a book of poems, after all, not a mystery novel. Still, one wonders why the three men go unpunished; and where are the mothers of these daughters? One possible answer to the missing mothers lies in “Spirits at the Edge of Bayonet Woods,” perhaps the book’s most powerful poem and certainly one of the most sympathetic poems about the working class or the rural poor that one is likely to read. Here Bohince offers an unflinching and unsentimental look at the lot of women on the homesteads:

Sooty hankies against our mouths, in the kitchen

chicken spitting in the fryer,

thick smoke rising, and we’re in the mineshafts,

the ones that swallowed our men

and cooked them and spat them into our beds.

Forgive us, Lord, we did not know them,

humpbacked and ruined, crawling toward us

wanting clean shirts, kisses, more children.

Tell me, what was a woman’s purpose in those woods?

Trading quails’ eggs for the babies’ medicine,

boiling ash and animal grease to shampoo coal dust

from our men’s curling hair?

. . . And though we pitied Grace,

the valley’s only suicide, we understood

when she wrote, I cannot go on here, in this place . . .

This book offers no comforting answers to any of its questions, and its conclusion is hair-raising. Likening herself to a lightning-struck walnut tree, the daughter of the murdered man says that she has been “split down [her] length and broken”; she’s “electrified by loss.” Like Dorothy, she must forget “that dream: // its yellow contagion, / . . . those accidents” if she is going to “live in the world.” By the time we reach the book’s coda, she has armed herself with her father’s .22. The gun “abandons its nine kinds of blackness: / its choke and muzzle, the comb / where his cheek rested . . . mine now.” As much “for Marie” as for herself, she zips on a camouflage jumpsuit “slumped in the hunting closet.” She recognizes the value in what they teach in church, that God “has given us such bounty— / this earth, for instance—such given / charity,” but she’s reached conclusions of her own. Now she sees “what the Book / omits, . . . how He allotted / for each gift one brutality / for balance.”

In Incident at the Edge of Bayonet Woods, Bohince may have done for the unified poetry collection what writers like Joyce Carol Oates, Donna Tartt, and Sabina Murray have done with the American novel in recent years. These writers remind us that the gothic’s primal subject matter is always contemporary, its form surprisingly flexible and powerful. They demonstrate that the gothic, like the comic grotesque, from Twain to Nathanael West to Donald Antrim and A. M. Homes, is peculiarly suited to challenging and correcting sentimental depictions of life in the rural corners of this country.

Published on March 19, 2015