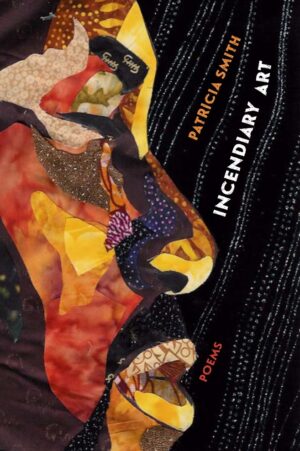

Incendiary Art

by Patricia Smith

reviewed by John S. O'Connor

President Obama struck a decidedly forward-thinking note in his farewell address this January, expounding his belief in the raw power of democracy. “For all our outward differences,” the president said, “we all share the same proud title: citizen.”

Such a sentiment stands in stark contrast to Patricia Smith’s brilliant and urgent new book of poems, Incendiary Art, her sixth collection. In it, Smith demands that readers recognize the racism and brutality that have always been part of American history before we dare look ahead to the future or even begin to understand our present.

Smith opens with a poem called “That Chile Emmett Till in That Casket.” The speaker’s language is colloquial, conversational—one of many personae Smith takes on in this book. For Smith, ventriloquism is empathy, and here she speaks as an African-American mother holding up the image of the murdered Till as a warning to her son:

See what happen when you don’t be careful? She meant white men could

turn you into a stupid reason for a suit …

The idea of transformation is central to Incendiary Art. Here, an unguarded life can become a mere occasion, a “stupid reason” for a funeral suit. A human life becomes an object lesson, yet another martyr’s mute warning. The only picture in the house, aside from the photo of Emmett Till, is that of the “glowing Jesus”—the ultimate symbol of murdered martyrdom. As the mother, speaking to her son, Smith writes: “there were / no pictures of you anywhere. You sparked no moral. You were alive.” The bleak options are anonymity and martyrdom.

The iconography of a “blue-eyed Jesus” starkly contrasts with the many other brutalized people of color who populate these poems, including Emmett Till, Rodney King, members of Operation Move, and four little girls in a Birmingham church. In “Incendiary Art: Birmingham, 1963,” Smith writes about these four girls: “Baby girls burn, boom. The Lord / dangles, festive and helpless.” In the face of such constant and savage violence, Jesus’s “azure-eyed swoop” seems decidedly remote, offering only the distant promise of redemption in “the next world.”

Smith is concerned with the current world—especially the iconography of representation in popular culture. In one poem, for example, she speaks as “Mammy Two Shoes,” the black maid who in the Tom and Jerry cartoons is reduced to mere synecdoche: a pair of shuffling slippers and bumbling servitude.

A great stage performer and a former national slam poetry champion, Smith is also a performer on the page. But here, perhaps more than in any of her previous books, the linguistic performance is always in the service of her subject. Even under the smothering pall of elegy, Smith’s language dazzles with the flash and heat of explosive diction, pulsing across the sonic wordscape. This book contains poetry of witness, yes, but also of outrage and indignation, a refusal to ignore the undertow of racist violence that has always accompanied our national history.

In the variety of poetic forms alone, Smith’s book is masterful: she writes elegies; sonnets (there are five sonnets titled “Emmett Till: Choose Your Own Adventure,” as if the eponymous victim had much choice, as if he really could have chosen); sestinas; and ghazals, all animated by incandescent language.

For example, in a stunning act of prosopopoeia, in “Incendiary Art: Tulsa, 1921,” Smith speaks from beyond the grave as a young man who, long before his murder in the Tulsa race riot of 1921, notices that “a branch droops, / already weary with me.” This man is rendered “numb / witness to what bullets shuck,” he who can already “smell three hundred / silences.” The number here is significant since the official state death count of the riot in 1921 was a mere 39, but at the time the Red Cross—and a 1990s commissioned review of the riot—placed the actual toll at 300. The massacre was effectively expunged from textbooks and newspapers, largely forgotten in the public record.

While deeply rooted in history, this book couldn’t be timelier; Incendiary Art is a book for the present, a howl into the chill indifference of the steady stream of news headlines about unarmed black men and women brutalized with impunity, often by officers of the law.

President Obama may have been right that we all share the same title “citizen,” but we have not all had access to the same rights and protections. As another grieving mother laments late in the book, the police are “armed with what they think are the rules,” and then, “Lord what are the rules?”

In an age of inconvenient “truths” and alternative facts, the fierce empathy and blazing truth of Incendiary Art has never been more necessary. These poems demand a reckoning.

Published on March 7, 2017