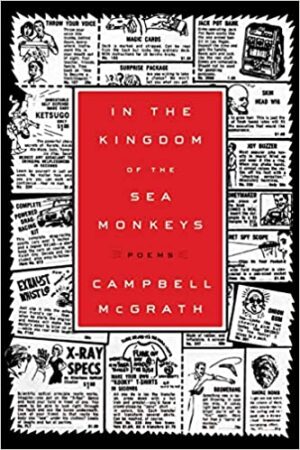

In The Kingdom of the Sea Monkeys

by Campbell McGrath

reviewed by Kevin T. O'Connor

Campbell McGrath has long been recognized as a wild, exuberant talent—a force of nature in the often decorous precincts of serious poetry. Through the 80s and 90s, when new formalisms were regaining ascendancy, he stayed true to a version of American romanticism and to the inspiration of open-formed innovators, including Whitman, Ginsberg, and O’Hara. His deservedly praised “The Bob Hope Poem” from his third book, Spring Comes to Chicago, works well as a long poem because it winds itself tightly around Hope as a figuration of the brilliant promise and banal corruption of the American experiment. McGrath’s technique of interspersing quotations from thinkers and artists—Wittgenstein, Veblen, Thoreau, et al.—provides critical frames for his flooding images of pop culture and materialistic excess. But whenever the poems verge on self-serious grandiloquence, McGrath deflates them with comic self-deprecation: “Am I a stooge of the popular culture machine?” He is a poet who balances social critique and lament with humor, phenomenological wonder, and emotional expressiveness.

McGrath’s voice can be bracingly inclusive and direct, demonstrating poetry as an activity of the spirit rather than a museum of polished artifacts. But it can also show the ragged edges of an art that values authenticity and truth-telling over aesthetic shaping and distillation. In the most recent of his eight collections, Seven Notebooks, when McGrath provides details of his family breakfast in Miami, he almost seems to be testing Yeats’s famous maxim, “Even when the poet seems most himself . . . he is never the bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast.” Though the prose journal entries interspersed with lyric meditations seem loose and lightly edited, they don’t lead me to wonder whether such a generous talent writes too much—just perhaps whether he publishes too much.

In The Kingdom of the Sea Monkeys marks McGrath’s return to lyric form—and to some extent, to lyric forms. One of the best poems in this volume, “Shopping for Pomegranates at Wal-Mart on New Year’s Day,” reads like a miniature reprise of the themes and virtues displayed in “The Bob Hope Poem,” where torrential images of the kitschy consumerist culture have been filtered through the assimilative lens of Hollywood and the mass media:

. . . this is the culture

in all its earnestness and absurdity, that it never rests

that each day is an eternity and every night is New Year’s Eve,

a cavalcade of B-list has-beens entirely unknown to me,

needy comedians and country singers in handsome Stetsons,

sitcom stars of every social trope and ethnic denomination,

pugilists ad oligarchs, femmes fatales and anointed virgins

throat slit in offering to the cannibal throng of Times Square.

Who are these people? I grow old. I lie unsleeping

As confetti falls, ash-girdled, robed in sweat and melancholy,

Click-shifting from QVC to reality TV, strings of commercials

The breath freshener, debt reconsolidation, a new car

Lacking any whisper of style or grace, like a final fetid gasp

from the lips of a dying Henry Ford, potato-faced actors

impersonating real people with real opinions

offered forth with idiot grins in the yellow, herniated studio light,

actual human beings, actual souls bought too cheaply.

That it never ends, O Lord, that it never ends!

In this rawly expressive poem, which is unafraid to make large general claims, satiric exasperation stays in playful tension with rapturous embrace,

That it is our divine monster, our factotum, our scourge.

That I can imagine nothing more beautiful

Than to propitiate such a god upon the seeds of my own heart.

Sometimes this poetry sounds as if Walt Whitman had done a revision on Brooklyn Ferry after taking seminars in the capitalist critique of the Frankfurt school.

I especially appreciate the humor in Campbell’s work. Early in this volume the light tone of “Emily and Walt” belies quirky depths when he extends the metaphor of Dickinson and Whitman as the eccentric parents of American poetry,

. . . now the house is ours

With its drawers full of odd

lines of verse and stairs that ascend to Godknows where, belfries and gymnasia,

the chapel, the workshop, aviaries, aria—we could never hope to fill it all.

Our voices are too smallfor its silences, too thin to spawn an echo.

That the shadows of these forebears loom large would be a dour pronouncement from some poets, but McGrath makes the point in a vividly amusing way.

The longer, loose-lined, meditative pieces in Part I like “Essay on Knowledge” and “The Mountain” don’t work as well without specific context or the tonal relief of McGrath’s self-deflating humor. Much more successful are shorter lyrics like “Figure for the Reckless Grace of Youth” and “Albuquerque” that tap into the rock-and-road romanticism that was a signature of McGrath’s early work. But any epiphanies here are threaded with contemplative lament, as if the quest to remember and understand turns everything elegiac: “No rain to speak of / just the glittering electricity / of a fast-moving storm passing through.”

In the Kingdom of the Sea Monkeys reflects an increasingly self-conscious poet, interrogating his own methods. The lead poem “Books” strikes a keynote for McGrath’s ambition to explore the creative source of myths and poems, the nighttime world of the unconscious, “the metaphysical library of the sea.” The collection’s title poem also evokes that world of the imaginative unconscious and an image “promised in the back pages of comic books of my childhood.” Disillusioned by the actual figures, which resemble tiny larvae rather than the majestic powers advertised, the poet poses a motive question for this book, “Where is the king of the Sea Monkeys, the Ruler of all memory?”

Perhaps all poems are about language as well as other matters, but Part II of In the Kingdom of the Sea Monkeys consists of poems specifically about poets and poetry—as if McGrath were playfully exhibiting stages in the gestation of a new aesthetic, or perhaps a re-embrace of an original source. “Notes on Compression,” “A Short Guide to Poetic Forms,” “Notes on Process,” and “Notes on Language and Meaning” join McGrath’s talents for satire with his predilection for comic self-critique in addressing his ambivalence about traditional poetic forms. Tributes range from a nostalgic remembrance of Allen Ginsberg, to tender homage to Frank O’Hara and Elizabeth Bishop, to a comic allegory about a tutelary “Cal” Lowell on a tiger hunt, to a full-scale channeling of Carl Sandburg on the prairie city of Chicago. Maybe the poetry world is too easy as a satirical target, but “Reading Series” and “Po Biz” gleefully eviscerate vanities and pretensions without ever sinking into self-serving malice. “Poem That Needs No Introduction,” a rude and raucous party of a poem, forever vitiates the notion that all Ars Poetica are introverted and precious. These broadsides really clear the ground for McGrath’s exhortations in “Poetry and the World” and “West Virginia” for a poetry which is less esoteric and self-circumscribed. The collection closes fittingly with “A Cattle Raid,” a rousing manifesto which challenges such timid insularity by proposing that an expansionist Republic of Poetry make raids across disciplines, genres, social classes, and cultures: “Be fearless, fellow riders! / Cross all borders!”

McGrath often exhibits such audacity, letting loose a poetry which can sometimes be formally underdressed or rough-mannered but which can also charm us with its large-hearted engagement and change us with its moral vision and passion.

Published on May 22, 2014