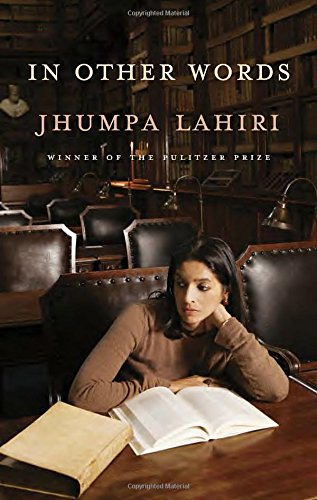

In Other Words

by Jhumpa Lahiri, translated by Ann Goldstein

reviewed by Yen Pham

In Other Words, Jhumpa Lahiri’s new memoir, is first and foremost a rare record of the joy and difficulty of learning a foreign language as an adult. Originally written in Italian and translated by Ann Goldstein, the book describes Lahiri’s decades-long quest to learn that language, distilling from the experience some universal truths. Among the difficulties: How language learning outside the ultra-plastic state of childhood places one in the posture of perpetual code-cracking sleuth; the way in which new grammars may also present unfamiliar ways of understanding time; and how even conversational facility, once achieved, gives one little purchase on written fluency. Among the joys (especially for a writer, and exuberantly communicated on every page): An inexhaustible trove of words to collect and treasure; the possibility of accessing a completely novel way of understanding the world; and the possibility of fashioning a completely novel self in that world. This last point is key, because the book is really about is Lahiri’s attempt to create a third space between the poles of America and Calcutta—the twin histories she feels compelled to escape, which, at the same time, remain constantly beside her.

Characters in Lahiri’s fiction frequently occupy the spaces between worlds. Here she writes directly of her own experience of being the American daughter of Bengali immigrants and of not quite belonging to either culture. It is a condition she cites as essential, rather than tangential, to her writing: “Ever since I was a child, I’ve belonged only to my words … If I didn’t write … I wouldn’t feel that I’m present on the earth.” The margins are a “zone where it’s impossible for me to feel rooted, but … the only zone where I think that, in some way, I belong.”

She discovers Italian as a young woman in Florence and dedicates herself to it with singular passion, reading and writing in it exclusively after she moves to Rome some twenty years later. Italian bears no relation to her ordinary life, and so studying it is an endeavor which at turns embarrasses her (in its superfluousness), depresses her (she is a lover whose ardor will never be returned), but ultimately liberates her. There is something of religious ecstasy in the joy of surrendering herself to something impossibly large, where the whole of possibility is continually withheld. It is an entirely foreign way to access a very familiar space, the reinvention of a lifelong trap through self-determination. Lahiri cannot escape a split identity, which she describes as “the torment of my life,” but the ways in which Italian alienates her are ways she has chosen, and that makes all the difference.

All this is explored with a vulnerability startling for readers of her fiction. In Other Words is a self-portrait of a writer accustomed to using writing as a form of dissimulation. You might not get this impression from her earlier books, but Lahiri is a person of strong opinions and unusual motivations: “What passes without being put into words … and, in a certain sense, purified by the crucible of writing has no meaning for me,” she writes. She suggests that, despite her own frustrations, she does not in fact desire total mastery of the language: “If everything were possible, what would be … the point of life? If it were possible to bridge the distance between me and Italian, I would stop writing in that language.”

Much of the book’s interest lies in the effect of a foreign language on the writing process. Italian forces Lahiri to give up perfectionism and makes her blind to the quality of her own prose, but it also turns writing into a kind of social communion with friends, teachers, and editors. An exercise in constraint, it increases her level of abstraction—the two short stories that are included in the volume are spare and striking, lacking names or settings. And yet, paradoxically, this abstraction produces her most personal work thus far. We understand why turning to a new language is the most extreme kind of metamorphosis she could attempt. This book is very much hers, and her first, she suggests, as an adult rather than a daughter.

Whether because of Lahiri’s evident pleasure in her adopted tongue, the method of composition, or because the book chronicles a journey that is necessarily long and incremental, In Other Words can be slow-moving and repetitive, with chapters that are sometimes indistinct from one another. There are also clichés that one wonders whether the Anglophone Lahiri would have written, such as when she describes Italian as like “a person met one day by chance, with whom I immediately feel a connection … as if I had known it for years.” But then again, that’s precisely her point: this is not a book the Anglophone Lahiri would have written, and that is, on balance, for the better rather than the worse. Lahiri has given up English, and all sorts of things with it: the lure of perfection, the notion that fiction is the freest form, or that her writing must “restore a lost country” to her parents. Whether she returns to English or proceeds in Italian, she has declared a new era for her writing. What follows?

Published on September 27, 2016