Icelight

by Ranjit Hoskote

reviewed by Sylee Gore

Ranjit Hoskote’s Icelight is a book of intimacies and glancing encounters that speaks to heritage, authorship, and friendship while encompassing human bonds and moments of solitude. This is a book for and about intimates. Five poems are dedicated to the memories of deceased individuals, a number of others to persons still living. These human connections are set across a natural terrain where the climate feels ever-present.

It’s mostly raining. The pages breathe a misty, ambiguous light. It is twilight and the world is full of luster. The leanly titled poems—“Rock,” “Foreigner,” “Dust,” “Clock,” “Temple,” “Departures”—are river stones worn smooth to their essential shapes. The cast of characters are the timeless figures of fairy tale—prisoner, hunchback, fisherman. Their simplicity suggests a primer, a dictionary of human experience.

Hoskote moves between physical experiences in dreamscapes and fablesque micronarratives in familiar worlds. In “Aubade,” a self in crisis reflects environmental catastrophe. The early morning song signals the start of a journey:

Wearing your salt mask, you face

the mulberry shadows.

The valley into which you’re rappelling

is you.

We catch glimpses of an aqueous landscape and days spent at the museum where past and present moments interconnect. “Departures” imagines lines connecting a bat and taxidermized orangutans in a museum of natural history that doubles as a “Museum of Cautionary Tales.”

Hoskote’s use of words like “shimmer,” “daimon,” “carnelian,” and “mizzle” feels fitting. He uses the italicized line to mark fragments drifting to us over a great body of water, as in “All Gods Travel”:

Here’s ripe stone here’s silvered creek

…………….here’s the call of a flute

……………trees praised in three tongues

……………a harvest of shade

We hear the speaker’s voice in profile, speaking to us although his eyes are fixed elsewhere. Reading these poems is like eavesdropping on intimacies or watching slippery black-and-white stories through a cinema doorway. In a poem for Goan photographer and writer Vivek Menezes, the poet writes:

Will there be time

…………….for you to bridge

…………….these causarina islands

……………yawning on a tide of fireflies?

To turn your back

…………….on lighthouse and seawall

…………….and be the foam

…………….on the crest

of the breaking waves?

We cannot know the history or objects he’s responding to—ours is the pleasure of poetry as artifact of human encounters. The pleasures of this triangulation between poet, addressee, and reader are considerable. When Hoskote speaks to the frailty of language, his voice takes on a grave Eliotic inflection. In “Monsoon Song,” he writes:

Peace held us captive.

We who could speak were sworn to silence.

We who could sing were beaten like drums.

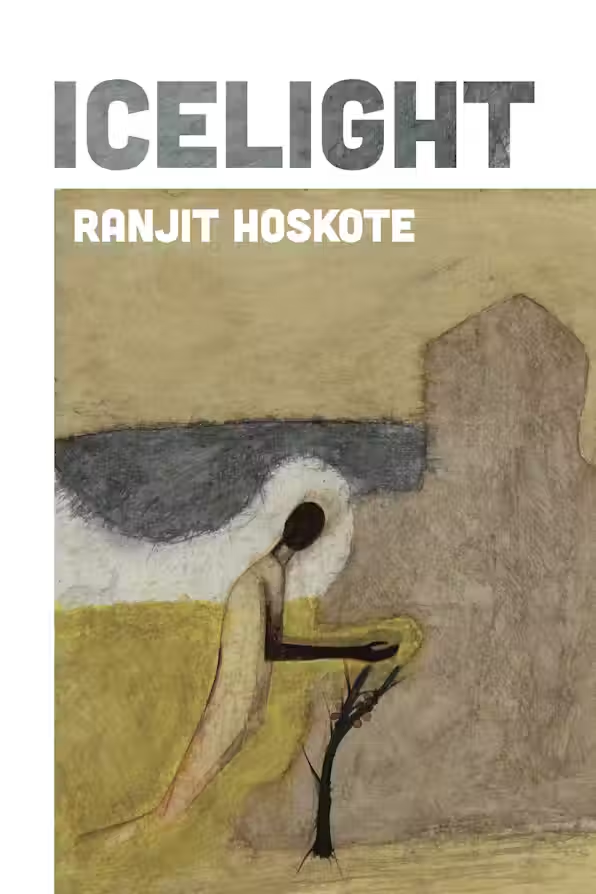

The proportions are epic, then intimate, mythic and mundane (as with the odd neighbors who prove the bane of suburban life). The scenes are shadowed, but never smudged. Their outlines may be jagged, but like the watercolor on the cover, the edges are sharp. The effect is of a chthonic exile. Imagination reanimates the taxidermized ape. As Hoskote writes, “The golden light you see is all dust.”

Published on June 26, 2024