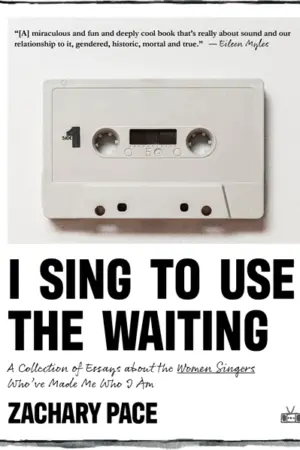

I Sing to Use the Waiting

by Zachary Pace

reviewed by Richard Scott Larson

Zachary Pace’s I Sing to Use the Waiting is a probing collection of essays on the transformative power of the human voice. Pace focuses specifically on women’s singing voices, titling the book with a line from an Emily Dickinson poem and referring lovingly and reverently to “the cultivation of my personality ignited from the incandescence of a woman singing.” Pace describes being enthralled as a toddler by a Gloria Estefan performance of “Conga” in an ’80s TV commercial in what serves as a telling origin story for Pace’s future affinities.

Pace recently began using gender-neutral pronouns, and it’s a decision that becomes an illuminating through-line in this collection of tributes to the women who helped shape Pace’s journey toward selfhood. With the subtitle A Collection of Essays About the Women Singers Who’ve Made Me Who I Am, the book argues that identity can be forged through intimate connections with outside influences, especially from popular culture, which so often functions as a mirror in which we catch our first glimpse of our true selves.

This is especially true of queer people, who cannot find a future in the ingredients of their early lives and must instead cast their gaze outward. But Pace also writes that “as an impressionable youngster, assembling my identity based on the authority of icons and moving images, I calibrated my value system to match the value systems that I witnessed onscreen.” The homophobia internalized from Disney films, which Pace discusses at length in a brilliant essay on Pocahontas, later had to be dismantled piece by piece.

“Are you a boy or a girl?” Pace recalls being asked as a child, the “queer timbre” of their voice inviting questions about masculinity and femininity. Writing about Nina Simone’s androgynous voice, Pace marvels that it “subverts the division between masculine and feminine pitch—the vocal range impossible to categorize without a visible body.” Pace often notes the mismatch between their own voice and body vis-à-vis gender presentation and wonders at the luxurious freedom of a genderless voice: “Disembodied, the voice has unfettered choice of gender to embody and desire.”

I Sing to Use the Waiting becomes a personal hagiography of the pop cultural figures who helped Pace cobble together an identity from within the isolation of the closet, with expansive pieces on Kim Gordon, Laurie Anderson, and Cher, among others. At the same time, the essays linger on the individual voice’s capacity to provoke feelings of shame. For example, we often cringe hearing our voices played back to us, knowing all too well that the queer voice—and the history of violence waged against it—is laid bare every time we open our mouths to speak.

The queer voice is often a shock to its speaker when heard for the first time, a confirmation of how we’ve been received thus far, despite our best efforts at concealment. We can sometimes hide inside our bodies, but it’s often our voices that give us away. Writing about listening to a recording of themselves singing as a child, Pace notes: “Queerness was still beyond my comprehension then, but I intuitively understood the sound could be considered dissonant from my gender presentation, and so, it struck me as embarrassing. Of hearing my own voice, this is my earliest memory.”

The voices and personae of the recording artists Pace idolizes grant insight into queerness. From the illicit presence of the Kabbalah in Madonna’s spiritual development, to the sheer otherworldliness of Cat Power’s vocal range, to Rihanna’s “queer powers of survival, adaptation, and dynamic negotiation in her articulations of selfhood,” to Whitney Houston’s struggle with the chasm between sexuality and religion, Pace expertly connects music to the performance of the self. “I do believe that a haunting melody has something to tell the hearer: something they need to know, something they already know but haven’t fully fathomed.”

The adoption of gender-neutral pronouns in 2021 by Frances Quinlan of the indie rock band Hop Along provides Pace with a model for doing the same the following year. With this decision, Pace continues a pattern of finding empowerment via female-born musical performers. “I’m learning to find affection for my queer voice,” Pace writes in the collection’s conclusion, the familiar arc of shame having culminated in a kind of reluctant acceptance—and, possibly, a pathway to self-love. Effortlessly alternating between criticism, theory, biographical journalism, and starkly personal memoir, Pace offers readers a mixtape of influences that feels deeply intimate, like something a friend would pass you in the hallway at school to be listened to later in the privacy of your bedroom, where only you can hear the words.

Published on April 30, 2024