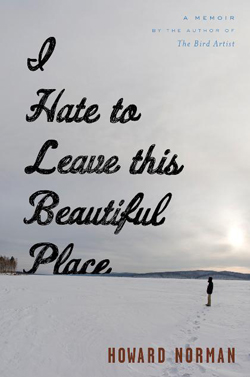

I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place

by Howard Norman

reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

Howard Norman’s memoir, I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place, is made up of five seemingly disjointed essays that span the period from the author’s youth to the near-present. It is less a smooth, well-planned journey than a kidnapping, with the reader as a blindfolded captive who has been taken to supposedly beautiful places, allowed to look around for a moment, and then thrown back into the car before he can digest what he has witnessed. While this narrative structure is disorienting, Norman succeeds in preserving the unexpectedness of life and memory—its making and retrieval—which is a common ground of our human existence.

With six novels and numerous prizes to his name, Norman is known best for what may be thought of as a northern gothic sensibility: his tales are set in places like Nova Scotia where the icy weather seems to invite the kind of loss and need to escape that irreparably pierces the soul and the memory. Birds flock to and from such regions and are central symbols in the fiction, and this motif finds its point of origin in the pages of his memoir. As suggested by the title of his 1995 novel, The Bird Artist, a National Book Award finalist and the first of a trilogy, real-life experiences bleed into all of his writing and specifically through birds, often in ways as inexplicable as their innate migratory patterns.

In the first installment of Norman’s memoir, we see how an early fascination with a bird—a mean-spirited swan he watched during his fifteenth summer, when he worked at a book mobile in Grand Rapids, Michigan—may have been what introduced them to Norman’s psyche in this way. That summer, a variety of realities hit him hard. After winning money in a radio contest, his estranged father makes a rare appearance and demands a share of the monies, illustrating a gross reversal of the parent-child provider roles; he felt the first ache of manipulative lust toward his older brother’s alluring girlfriend, Paris; and he accidentally kills the swan (read: Sophocles in vivo). Such events are undoubtedly of the type that he says “will not allow you to forget them . . . melancholy that is forever part of your personal history.” They shape his life as both a man and a writer.

Each subsequent chapter features a similar bird that seems to embody, even subconsciously, the pain of the memory manifesting itself on the page. When his college girlfriend, a painter whose muses are seagulls, dies in a plane crash, he seeks them out in homage to her too-short life. In the 1980s he spends a winter in the Canadian Northwest Territory and crafts a myth of an Inuit man who is turned into a bird. There is the kingfisher ill with a parasite as Norman, struck by a mysterious fever, sees Confederate ghosts in his backyard and staves off his brother’s parasitic demands to help him cross the border to avoid police detainment. Last, and most devastatingly, our mind’s eye is graffitied with the image of a kestrel circling the Vermont house they rented to a disturbed poet who kills her baby son and then commits suicide.

In the context of the separate narratives, these birds are nothing more than incidental details—writerly flourishes that, it might seem, only bear significance in a third-party analysis like this. But Norman seems painfully aware of what these birds mean. They’re not quite harbingers but rather a kind of pathetic fallacy stemming from nature itself. Seeing these symptom-sharing birds able to cure themselves and enter seamlessly into the rhythm of their lives despite obstacles, Norman comes to accept his own malaise and thereby the adage of his elderly, Holocaust-obsessed uncle Isador: “I cling to my regrets, once I discover which ones won’t go away. I rely on them for unhappiness. It keeps me connected to the past.” Memory’s not something we can escape, and it’s a built-in function to go back and visit every once and a while.

Despite this connection to ornithological habits, Norman’s work never devolves into a predictable series of departure and return. As he writes, “Life does not travel from point A to point B. A whole world of impudent detours, unbridled perplexities, degrading sorrows, and exacting joys can befall a person.” In taking up I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place, the reader thus enters into a silent agreement of uncertainty, embarking upon a journey that may lead us into an etherized night or a phase where “everything I loved most happened most every day.” And if the latter—which is how Norman ultimately describes these disturbing times—we won’t mind the insecurity at all. In fact, we’ll be even better able to appreciate his book’s title and apply it to our own here and now, and our there and then, in equal measure.

Published on August 5, 2014