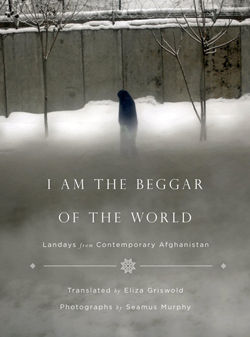

I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan

translated by Elisa Griswold

reviewed by Elizabeth T. Gray Jr.

In I Am the Beggar of the World poet and journalist Eliza Griswold offers a rich and graceful collection of Pashto landays, short folk poems recited or sung by women native to the Pashtun areas of eastern Afghanistan and western Pakistan. The landay is a vibrant, clandestine, and ancient tradition. Within the confines of Pashtun culture a woman is supposed to be invisible, silent, and compliant, an asset—and a threat or liability—to her male kin and their honor. No Pashtun woman should boldly recite a poem like this one, shared with Griswold in 2012 in a classroom filled with sixty Pashtun women: “Making love to an old man / is like fucking a shriveled corn stalk black with mold.”

Griswold’s introduction offers a succinct description of the form and its practice:

A landay has only a few formal properties. Each has twenty-two syllables: nine in the first line; thirteen in the second. The poem ends with the sound ma or na. Sometimes landays rhyme, but more often not. In Pashto, they lilt internally from word to word in a kind of two-line lullaby that belies the sharpness of their content, which is distinctive not only for its beauty, bawdiness, and wit, but also for its piercing ability to articulate a common truth about love, grief, separation, homeland, and war. Within these five main tropes, the couplets express a collective fury, a lament, an earthy joke, a love of home, a longing for the end of separation, a call to arms, all of which frustrate any facile image of a Pashtun woman as nothing but a mute ghost beneath a blue burqua.

Griswold offers us more than one hundred landays, clustered according to the tropes laid out above and set like small gems on the right hand pages. Brief bits of text on a following page sometimes provides context for the imagery or describe her source for the poem—a wedding party, a clandestine meeting with women in a park, or an ethnographer’s collection of Pashtun verse.

One theory holds that landays were born in nomad caravans, and that their form reflects call and response during the course of the journey. Some landays may reflect that original context:

Climb to the brow of the hill and sight

where my darling’s caravan will tent tonight.

and others have probably remained unchanged through centuries:

When sisters sit together, they always praise their brothers.

When brothers sit together, they sell their sisters to others.

Some graft modern imagery into old lines. In this one, the Americans have displaced the British and then the Russians in line two:

Leave your sword and fetch your gun.

Away to the mountains, the Americans have come.

And here a brave lady taunts her beloved:

How much simpler can love be?

Let’s get engaged. Text me.

Carefully placed among the poems are roughly fifty photos taken in Afghanistan by Seamus Murphy, Griswold’s long-standing collaborator. Some of these stunning images capture the same kinds of paradox found in the poems. The frontispiece, for example, is an image of what looks like an unmanned military surveillance vehicle hanging in the air above the broken rim of an ancient Afghan fort. Other photos mirror or comment on the poems facing them, enacting the juxtaposition of beauty and ruin, what is open and what is hidden.

While landays are unrhymed in Pashto, Griswold has chosen to translate the poems into loosely-rhymed couplets, to replicate the feeling of English oral folk poetry. This works beautifully and doesn’t feel forced. Indeed, the form feels very aligned with Griswold’s own verse. Here are the last two lines of “Occupation,” from her 2007 collection Wideawake Field:

Two years ago the Talibs favored boys and left the girls alone.

A woman then was worth her weight in stone.

As Griswold reminds us, for the brave young women who shared their songs with her, the western occupation of Afghanistan has opened the lives of young women in ways never imagined. The imminent departure of Karzai and NATO forces fills them with both a sense of promise and great foreboding. But now we have heard their songs.

Published on June 24, 2014